|

|

|

The approach from the main gate of the Nezu Museum, designed by Kengo Kuma. Photo © Mitsumasa Fujitsuka |

If the Eskimos really have twenty-five words for snow, then the Japanese must have nearly as many for iris. Though the distinctions remain far from obvious to my untrained eye, recent iris-viewing opportunities have motivated me to study up on the different names assigned to the varieties that bloom in Japanese gardens in the spring: ichihatsu, ayame, hanashobu, kakitsubata...

Of these, the kakitsubata (the prosaic "rabbit-ear iris" in English) seems to occupy a special place in Japanese hearts. Its affinity for damp, marshy soil makes it ideal for planting along garden ponds, and its sensual violet blossoms make it a favorite subject of artists over the centuries.

|

|

|

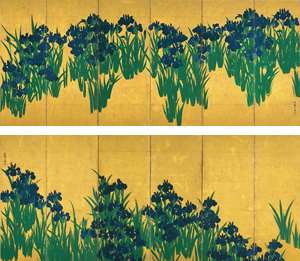

The right (above) and left screens of Kakitsubata-zu (Irises) by Ogata Korin, Edo period, 18th century. |

Inarguably the most renowned iris painting in Japan, if not the world, is the glorious

Kakitsubata-zu by Ogata Korin (1658-1716). The proud owner of this masterpiece, a designated National Treasure, is the Nezu Museum in Tokyo.

Painted on a pair of six-panel, gilt-paper screens, the irises were the centerpiece of a recent exhibition at the Nezu of works by Korin and other artists of the classical Rimpa school. Timed to coincide with the blooming of real live

kakitsubata in the museum's extensive and lovely tea garden, this was the first display of the screens in four years. (Though the show has since closed, the Nezu has announced that it will resume exhibiting the screens every spring.)

|

|

|

Kakitsubata irises blooming in the pond of the Nezu Museum garden. |

The pair of paintings, which side by side occupy an entire wall of the Nezu's main gallery, are nothing like the busy, intricate floral motifs of typical screens of the same period. The simple, repeating pattern of the irises, painted with bold, calligraphic brushstrokes and no outlines, appears almost abstract. Korin uses only three colors: the blue of the petals, the green of the stalks, and the gold background. Nothing but irises, yet with a subtle difference between the two screens: where the plants on the right side are painted in their entirety, filling the entire field, we see only their top halves on the left, emphasizing the flowers and the expanse of golden space behind them. Most strikingly, the blossoms are not violet at all. Korin used

gunjo -- powdered azurite -- to render them in a deep blue that is closer to indigo.

The Nezu owes its remarkable collection -- some 7,000 objects, seven National Treasures, 87 Important Cultural Properties -- to the discerning eye and deep pockets of one man, railway magnate Kaichiro Nezu (1860-1940). Though hardly unique among Japanese captains of industry in his love of fine art and a willingness to spend much of his fortune acquiring it (corporate museums built around their founders' collections abound here), Nezu's tastes were more refined than most. His great loves appear to have been ancient Buddhist statuary, much of it imported from China; classical Japanese art like Korin's works; and bowls and other utensils associated with the tea ceremony (of which Nezu was a devotee).

Hence one of the most eye-catching displays at the museum is the reception line of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas that greet the visitor upon entering the main hall, ranging from a third-century Maitreya in the Ghandara style of central Asia to 13th-century wooden statues from Japanese temples.

The Nezu reopened in 2009 after nearly four years of renovation, which included the construction of a new building designed by contemporary architect Kengo Kuma. There are nice touches of traditional and modern, such as a long bamboo-lined entryway and large glass windows that look out on the Nezu garden. But it is the garden itself (or rather, Kuma's wise way of bringing it right into the museum) that dominates. Covering 17,000 square meters, it surrounds the museum with dense foliage, keeps the bustling city at bay, and contains four rustic teahouses (the property is Kaichiro's original estate) as well as a pond that is, as one might guess, full of

kakitsubata in bloom. Although neither Korinfs irises nor those in the pond will reappear at the Nezu till next spring, you can view a splendid display of

hanashobu, a later-blooming variety, till late June in the Meiji Shrine gardens just down the street.

|

|

|

| The main hall of the Nezu Museum, with Buddhist statuary. Photo © Mitsumasa Fujitsuka |

|

Statue of the Bodhisattva Maitreya, Ghandara, Kushan period, 3rd century. Photo © Mitsumasa Fujitsuka

All photos courtesy of the Nezu Museum. |

|

|