|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Plaster Paintings and Sea-Slug Walls: Matsuzaki's Chohachi Museum

Alan Gleason |

|

|

|

|

"Dragon" by Chohachi Irie, Izu-no-Chohachi Museum. |

Literally "sea-slug wall," namako-kabe is the unflattering name for the distinctive diamond-grid patterns that adorn surviving Edo-era buildings in certain parts of Japan. Best known to tourists are the concentrations of these structures in Kurashiki and elsewhere in the western part of the country. However, an equally well preserved namako-kabe enclave can be found closer to Tokyo, in the sleepy fishing port of Matsuzaki.

Located on the southwest coast of the Izu Peninsula, Matsuzaki is surrounded by steep hills, nearly an hour's drive from a train station, and refreshingly devoid of tourism claptrap despite its relative proximity to the capital. Isolation has protected the town from war, overdevelopment, and other manmade calamities of the past century; today it boasts some of Japan's loveliest specimens of 19th-century architecture, particularly the quasi-Western structures that came into vogue in the early Meiji era. (Not coincidentally, the "black ships" that opened Japan to western trade, and the first American consulate permitted by the Shogunate, both made their appearance in Shimoda, just across the peninsula from Matsuzaki.)

Though the attractive black-and-white checkerboard of namako-kabe design does somewhat resemble the bricks-and-mortar construction of Western buildings, its popularity precedes Western architectural influence and stems from an Edo-era need to protect important structures from fire and flood. Black slate tiles applied to storehouse walls were reinforced with thick, mounded strips of the fine plaster known as shikkui. The shiny round contours of plaster inspired a visual association with the sea-slug, surely one of the ocean's ugliest critters. Numerous designs were tested, but the diagonal diamond pattern that attracts tourists' cameras today became prevalent thanks to its superior ability to shed rainwater.

|

|

|

Chohachi Irie (1815-1889). |

Plastering was therefore a respected profession in Matsuzaki as elsewhere, so perhaps it is not surprising that eventually, one such artisan would apply his skills with the trowel to the fine arts. This is just what native son Chohachi Irie (1815-1889) did, producing an oeuvre of fresco works equal to the paintings his contemporaries executed with conventional brushes.

A poor farm boy, Chohachi was apprenticed to a local plasterer at age twelve, but exhibited artistic talent and ambitions early on. At nineteen he journeyed to Edo to study painting with the venerable Kano School, and soon began experimenting with plaster and trowel in the Nihonga genre. His motifs are standard Nihonga fare -- landscapes (particularly views of Mt. Fuji from the Izu coast), historical figures, goddesses, cranes, dragons -- as are his colors, the naturally-occurring pigments of traditional Nihonga. What makes his work literally stand out is the three-dimensionality of the plaster. Though this could easily have become a gimmick (a Nihonga equivalent to the 3D movie?), Chohachi's artistry lies in his use of fresco techniques in the service of his subject matter, tastefully layering the plaster to enhance his motifs, never to exaggerate them. Though photo images don't do justice to the effect, it can be seen to some extent in his "Dragon," in which two parallel sine waves of plaster slash across the painting, graphically dramatizing the speed and force of the mythical creature's rush across the sky.

Chohachi gained fame in his lifetime for his pioneering work, earning accolades even from the jaded art critics in the capital, as well as commissions to paint the walls of numerous Buddhist temple sanctuaries. Sadly, most of these monumental works were lost in the Kanto Earthquake that devastated Tokyo in 1923.

|

|

|

Front entrance of the Izu-no-Chohachi Museum, Matsuzaki, designed by Osamu Nishiyama. |

Fortunately the town of Matsuzaki saw fit to honor its favorite son by building the Izu-no-Chohachi Museum in 1984. Housing some fifty of Chohachi's works, the building is nearly as unique as its collection. In jarring contrast to the surrounding townscape, the museum seems to be a willfully eccentric assemblage of postmodern elements, but there is a certain logic to architect Osamu Ishiyama's choices. Indeed, the building won him the Tenth Isoya Yoshida Prize, one of Japan's highest architectural honors. With a shining white plaster façade that stands out starkly against the verdant hillside behind it, the structure opens up inside, where a glassed-in passageway on the second floor offers an aerial view of the authentic namako-kabe walls that line the courtyard below. The cupola over the entrance and the columns and archways inside at first strike one as a gratuitous rococo conceit, but have their inspiration in the quasi-Victorian style of the Meiji-era buildings that are Matsuzaki's pride.

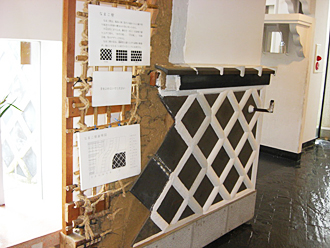

Besides displaying Chohachi's works, the museum provides an instant education in namako-kabe construction, with a cutaway model revealing the different layers that make up the walls and a display of the tools used to build them. The trowel collection alone is something to behold -- not only because of the impressive diversity of sizes and shapes of this prosaic implement, but because it reminds us of Chohachi's remarkable accomplishment in creating fine art with such tools.

|

|

|

| Display model of namako-kabe construction, Izu-no-Chohachi Museum. |

|

A classic example of namako-kabe architecture in the town of Matsuzaki.

All images courtesy of the Izu-no-Chohachi Museum and Matsuzaki Town |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Izu-no-Chohachi Museum |

|

|

|

Matsuzaki 23, Matsuzaki-cho, Kamo-gun, Shizuoka Prefecture

Phone: 0558-42-2540

Hours: 9:00 - 17:00 (open all year, 7 days a week)

Transportation: Matsuzaki is a 50-minute bus ride from Izukyu-Shimoda station, which is 2 1/2 hours southwest of Tokyo on the Izukyu Line. |

|

|

|

|

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for 25 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|