|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Flying High in Nihonbashi: Tokyo's Kite Museum

Alan Gleason |

|

|

|

|

| The interior of the Kite Museum, viewed from the entrance. |

|

A kite portrait of Kite Museum founder Shingo Modegi, next to an octopus kite. |

Tucked away on the fifth floor of a nondescript downtown Tokyo office building, the room is of modest dimensions. Yet to enter it is to step back in time, into one of the impossibly crowded little neighborhood toyshops, stuffed with gaudily dyed kites, paper balloons, dolls, model boats and planes, that I remember from my Tokyo childhood.

The room is what is surely one of the most compact and jam-packed exhibit spaces in all of Japan: the Kite Museum in Nihonbashi. Every inch of aisle, wall and ceiling is covered with a dizzying array of kites of every description. They hail not only from Japan but also China, Indonesia, Colombia, New Zealand, France -- a truly global display of ingeniously constructed flying machines. Kites are indeed an art form unto themselves.

The Kite Museum's founder, the late Shingo Modegi, started out as a restaurateur (his son Masaaki still runs the Taimeiken Restaurant on the first floor of the building). Modegi's love of kites prompted him to found the Japan Kite Association in 1969 and, as his own collection burgeoned, the Kite Museum in 1977. Now operated by the association, which Masaaki chairs, the museum currently owns some 3,000 kites, of which it displays about 300 at a time.

|

|

|

| A corner of the museum. Note the mukade-dako (centipede kite) hanging from the ceiling. |

|

Papier-mache head of a Chinese dragon kite, formerly part of a mukade-dako. |

At the heart of the collection are the lavishly illustrated Edo nishiki-e dako -- kites dating back to Tokyo's golden days as Edo, the seat of the Shogunate. These masterpieces of kitemaking, with their bold ukiyo-e images of Kabuki actors, mythical creatures and legendary warriors, seem almost too pretty to toss into the air. But they are definitely built to fly, constructed of bamboo and a sturdy variety of handmade washi paper made from kozo, a type of mulberry fiber.

|

|

|

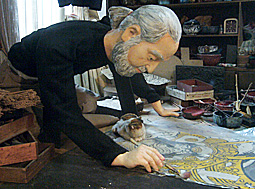

A life-size likeness of legendary Edo dako artist Teizo Hashimoto (1904-1991) at work in his studio, with one of his beloved cats. |

Japanese kitemakers have always displayed a playful sense of humor. It helps that the word for kite -- tako -- is a homonym for octopus, with predictable results. Then there are the jointed mukade-dako -- "centipede kites," made of numerous sections connected by strings, that wriggle snakily in the wind.

More recently, Japanese kitemakers have built elaborate kite models, with full paper rigging, of sailing ships like the Nihon-maru. As the museum's photos attest, these miniature galleons make a ghostly spectacle as they float across the sky. Other treasures tucked in the corners of the museum include a Maori bamboo bird kite and a huge Chinese dragon head that once belonged to a massive "centipede" kite.

Kite enthusiasts will not be disappointed in the museum's shop, which at first glance is virtually indistinguishable from the glorious jumble of the exhibit section. Besides an attractive selection of Japanese kites and kitemaking materials (polyester tends to trump washi these days), there are kite calendars, kite t-shirts, and reproductions of ukiyo-e depicting kite fliers on the riverbanks of old Edo. Some forms of amusement are timeless, and some transcend amusement to become art.

|

|

|

| A Nihon-maru sailing ship kite, built by Kikuzo Watanabe. |

|

Another Nihon-maru kite built by Morio Yajima, captured in flight (photo published by Seibundo Shinkosha, 1978).

Photos by Alan Gleason except where otherwise noted. All images by permission of the Kite Museum. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Japan Kite Association |

|

Kite Museum |

|

|

|

5th floor, Taimeiken Restaurant, 1-12-10 Nihonbashi, Chuo-ku, Tokyo

Phone: 03-3271-2465

Hours: 11:00 - 17:00 Monday through Saturday, except national holidays

Transportation: One-minute walk from exit C5 of Metro Nihonbashi Station, or a ten-minute walk from the Yaesu central exit of JR Tokyo Station. |

|

|

|

|

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for 25 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|