|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ghost World: Shigeru Mizuki at the Hachioji Yume Art Museum

Alan Gleason |

|

|

|

|

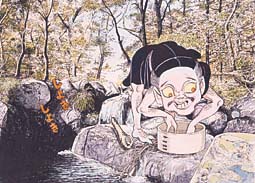

Azuki-arai: a yokai who spends his time washing azuki beans by mountain streams. Hungry travelers drawn by the shoki-shoki sound of the beans inevitably lose their footing and fall in the stream (from Yamanashi Prefecture). Shigeru Mizuki,

© Mizuki Productions |

|

The Mizuki exhibition at Hachioji Yume Art Museum, where visitors are greeted by a statue of Kitaro with his father, the eyeball, perched on his head. |

In the Japanese manga/animation pantheon, Shigeru Mizuki ranks, both in critical acclaim and public visibility, with the likes of Osamu Tezuka and Hayao Miyazaki. His name may be less recognized abroad, but it is ubiquitous in his home country. Last year's big TV hit was a humorous biographical series about the travails of Mizuki's wife, and this past New Year's Eve, the annual music extravaganza Kohaku Utagassen featured a popular young band playing the Mizuki show's theme song.

Much of Mizuki's notoriety stems from his association with yokai, the indigenous supernatural beings (the term embraces all manner of ghosts, goblins, monsters, and even haunted versions of everyday objects) that have populated Japanese folklore since time immemorial. Mizuki created his most famous manga and animation character, Kitaro, to tie together yokai tales from around the country. Half yokai and half human, Kitaro's friends and relatives are a bizarre crew of creepy critters that, despite their spooky attributes, are beloved by generations of postwar Japanese. (Kitaro's father appears in the form of a single eyeball with arms and legs, who sometimes perches inside the socket of Kitaro's missing eye.) Some of Mizuki's creations are straight out of his own seemingly limitless imagination, but many are based on traditional yokai myths, an obsession of Mizuki's that goes back to his childhood.

Born in 1922 in Tottori Prefecture, Mizuki grew up an avid consumer of the scary tales told by the neighborhood grannies. Today, after decades of extensive research, he may be the world's foremost expert on supernatural folklore, and has published several books on the subject. His biggest contribution, however, has surely been to re-introduce contemporary urban Japanese to their own haunted heritage through his wildly popular Ge-Ge-Ge no Kitaro animated TV series. His influence extends throughout Japanese pop culture -- the yokai-like creatures that appear in Studio Ghibli hits like My Neighbor Totoro and Spirited Away are just one example.

|

|

|

| The Yume Museum shop offers a wide range of Mizuki "goods," including these grotesquely winsome stuffed eyeballs in various sizes. |

|

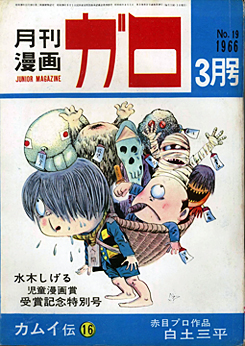

The March 1966 issue of Garo, with cover art by Mizuki (published by Seirindo). |

Mizuki came relatively late to success, but his pet characters -- notably Kitaro -- date back to his earliest work before and after World War II, when he eked out a living drawing pictures for the kami-shibai (paper play) market. When this genre of kids-oriented street entertainment met its demise with the advent of TV in the fifties, he moved on to drawing manga for kashi-bon rental libraries, bringing Kitaro and his cohorts with him. Finally, in 1959, Mizuki was hired to draw serials for Kodansha's Shonen Magazine, one of the first manga weeklies, and his career, and Kitaro's popularity, began to take off.

The thoroughgoing retrospective now at the Hachioji Yume Art Museum (until January 23) is inspired, no doubt, by the hype surrounding the recent TV hit about Mr. and Mrs. Mizuki, but its curators have done fans a service by introducing other highlights of Mizuki's career besides his Kitaro franchise. An example of how Mizuki has parlayed his yokai fixation in novel directions is the hilarious "Fifty-Three Stages of the Yokai-do," a parody of Hiroshige's famous 19th-century woodcuts of views along the Tokaido highway. Mizuki has faithfully reproduced the background of every one of Hiroshige's prints, but populated them with a whole menagerie of yokai. The entire series is on view at the Yume Museum.

Another room is devoted to the seminal manga monthly Garo, which was launched in 1964 (it ceased publication in 2002). A favorite of sixties student activists and hippies, Garo single-handedly pioneered the more serious, adult-oriented genre of manga known as gekiga ("dramatic pictures"); among its flagship artists were Sanpei Shirato, Mizuki, and Mizuki's protégé Yoshiharu Tsuge. As befits its role in showcasing a new generation and style of manga artistry -- comparable in its subversive impact to underground comix in America -- Garo receives ample attention in the current exhibit, and the Yume Museum staff is to be commended for highlighting the magazine as a phenomenon in its own right.

Another, more sober side of Mizuki's output is also on display. Drafted into the Imperial Japanese Army in 1942, Mizuki was shipped to the South Pacific island of New Britain, where he lost his left arm in an Allied attack and was nursed back to health by local tribespeople. His injury actually saved him from almost certain death, as the rest of his battalion was subsequently ordered to sacrifice itself in a meaningless banzai charge against a vastly superior enemy force. Mizuki has written at length, both in manga and text, about his war experiences and the folly and brutality of the Japanese military order. His 1973 graphic novel Soin Gyokusai Seyo! (Banzai Charge!) is one of the masterpieces of Japanese antiwar literature in any genre. Panels from Mizuki's war-themed work place the whimsical grotesqueries of his yokai world in grim perspective.

Opened in 2003, the Yume Museum is a municipal facility run by the city of Hachioji, a large suburb on the western edge of the Tokyo conurbation. With a mandate to serve Hachioji citizens as a "museum for daily life," its exhibitions run the gamut from Nihonga to ceramics to contemporary art to popular culture, but there is definitely a tendency to emphasize the pop end of the spectrum. The Mizuki show, however, is proof that even a pop icon can provide inspiration on so many levels -- literary, ethnological, sociopolitical -- that he drags an adoring public willy-nilly to unexpected insights about life and art.

|

|

|

Gasha-dokuro: a giant skeleton spawned by the angry spirits of wayfarers who died by the roadside (a yokai from Hiroshima Prefecture). Shigeru Mizuki,

© Mizuki Productions

|

|

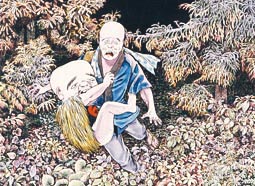

Konaki-jijii: a yokai who hides deep in the forest, bawling like a baby; travelers who pick him up can't shake him off and eventually die in their tracks (from Tokushima Prefecture). Shigeru Mizuki,

© Mizuki Productions

|

|

|

|

|

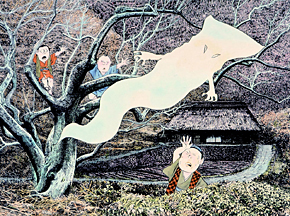

Ittan-momen: a yokai in the form of a sheet of cotton cloth that wraps itself around unsuspecting passersby (from Kagoshima Prefecture). Shigeru Mizuki,

© Mizuki Productions

|

|

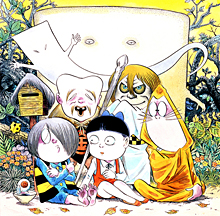

Kitaro and family relaxing in Tottori Prefecture; Kitaro's father bathes in a teacup at left. Shigeru Mizuki,

© Mizuki Productions

All images courtesy of the Hachioji Yume Art Museum

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(For a comprehensive and entertaining introduction to the yokai world, read Yokai Attack! by Hiroko Yoda and Matt Alt.)

|

|

The World of Mizuki Shigeru |

|

26 November 2010 - 23 January 2011 |

|

Hachioji Yume Art Museum |

|

2F, View Tower Hachioji, 8-1 Yoka-machi, Hachioji City, Tokyo

Phone: 0426-21-6777

Hours: 10:00-19:00 (admission until 18:30) (closed Mondays and 29 December - 3 January)

Transportation: 15-minute walk from the north exit of JR Hachioji station (Chuo Line) or 18-minute walk from Keio-Hachioji station (Keio Line)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for 25 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|