|

|

|

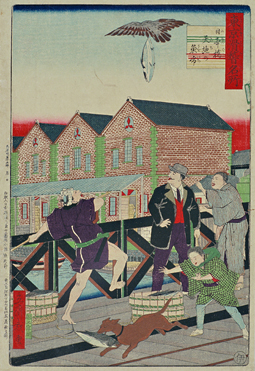

| Utagawa Hiroshige III, "Tokyo Pleasantries: The Fish Market at Nihonbashi Tenchi" (1883). A hapless fishmonger loses one fish to a bird and another to a dog, while a foreigner laughs. In the background is the brick Mitsubishi warehouse. |

|

Utagawa Hiroshige III, "Tokyo Pleasantries: Battledore and Shuttlecock Players Dealing a Blow to the Jaw in Yanagibashi" (1883). A Western-attired gentleman's tophat goes flying when he is struck by an errant battledore. |

"Meiji Restoration" is a euphemism if there ever was one. Basically a coup d'etat by disgruntled daimyo, followed by a bloody civil war, the upheaval that toppled the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1868 and "restored" the emperor to his rightful position (albeit as little more than a figurehead) took several years to subside. When it did, however, it ushered in a period of relatively peaceful, but no less profound, cultural revolution during which Japan began modernizing and Westernizing at a pace never seen in Asia before or since. The process had already begun under the Shogun (Perry and his black ships had shown up nearly two decades earlier), but by the 1870s Japan's major cities had gaslit streets, railroads, and citizens in Western dress jostling with those in traditional kimono, loincloths, clogs and topknots.

It was a great time to be a caricaturist, and woodblock artists rose to the occasion. The disciples of Hiroshige and other masters of a previous generation began churning out witty and often hilarious depictions of urban Japanese negotiating the dizzying changes in fashion and lifestyle against a backdrop of shiny new Victorian buildings and steam-belching locomotives. Adding to the sense of dramatic departure from the older style of ukiyo-e, these "Meiji nishiki-e" were often inked in the gaudy reds and purples of aniline dyes recently imported from Europe. Ukiyo-e connoisseurs may have sniffed disdainfully at the garish chemical hues, and many still do, but in a way they were perfect for the radical new subject matter.

An excellent collection of Meiji nishiki-e is owned by none other than Tokyo Gas Co., and the reason is quite simple. The introduction of gas as a source of illumination in the early 1870s transformed life in Japan's cities, and gaslights figure prominently in illustrations of the period. Housed in a pair of restored late-Meiji brick buildings in the western Tokyo suburb of Kodaira, the utility's attractively appointed Gas Museum is currently showing several dozen of its most humorous nishiki-e in an immensely enjoyable exhibition entitled Warai kara miru Tokyo meisho, or literally "A Comic View of Famous Places in Tokyo." Unfortunately for non-Japanese visitors, none of the generous explanatory text accompanying the artwork has been translated into English; fortunately, the visual gags need no translation.

|

|

|

| Utagawa Hiroshige III, "Famous Sites in Tokyo: Brick Buildings on the Ginza" (1879). A lamplighter goes about his work during cherry-blossom season; behind him, a horsedrawn carriage and rickshaw rush past each other on the busy Ginza. |

|

Shosai Ikkei, "Thirty-Six Comic Scenes of Famous Places in Tokyo: Kameido Tenjin Shrine at New Year" (1872). A horse gets entangled in festival decorations and knocks over a vendor's stall. |

Pride of place in the show goes to Utagawa Hiroshige III (1842-94), not the son of the original Hiroshige but the second of his disciples to marry the master's daughter, after she and Hiroshige II had divorced. Born Goto Torakichi and initially known by the artistic name Shigemasa, this enterprising third Hiroshige lacked his teacher's genius but displayed a knack for sharp visual commentary, verging on slapstick, on the trends of the times. Calling himself the "Meiji Hiroshige," he produced a series of

Famous Comic Views of Tokyo that depict the citizens of the capital drinking, brawling, taking pratfalls, gawking at foreigners, and generally buffeted to and fro by the winds of change.

Less prestigiously named than Hiroshige III but possessed of just as sublime a sense of the absurd was Shosai Ikkei, whose origins and fate are as much a mystery as those of the legendary Sharaku. Ikkei was active as an ukiyo-e artist between 1870 and 1874, then disappeared. His grand opus,

Thirty-Six Comic Scenes of Famous Places in Tokyo (1872), demonstrates a more fluid line and artistic sense of composition than Hiroshige III. Some of his works could be taken for those of a contemporary of Hiroshige I and Hokusai, were it not for the offhand yet telltale signs of Westernization -- shoes instead of sandals, umbrellas instead of paper parasols, short haircuts on men, corked wine bottles on a bar counter.

Ikkei and Hiroshige III did not always milk the East-meets-West theme for laughs. Many of their works straightforwardly document the Meiji era's wild juxtapositions of old and new architecture, custom, and dress, or use these novelties as backdrops for bits of mischief that have nothing to do with culture clashes per se: a bird stealing a fishmonger's fish, for example, while a foreigner in a bowler hat looks on with amusement. When they do poke fun at clumsy Japanese attempts at modernity, it is usually at the expense of pretension, like the dandy who stumbles in his fancy Western shoes and tumbles head over heels from a steeply arched garden bridge.

|

|

|

| Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, "Tokyo Enlightenment Pleasantries: Nipposha, Owari-cho" (date unknown). City slickers guffaw at two elderly bumpkins praying reverently to a brightly lit office building. |

|

A crab-shaped gas stove, the No. 17 OS (1937), on display in The House of Gas for Life, a restored 1912 brick building at the Gas Museum. |

Other artists found comic relief in the confusion engendered by the pace of change. Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, best known for his grotesqueries of violent crimes and ghosts, is represented here by works with a lighter, more satirical touch: in one woodcut, a drunk mistakes a police box for a public urinal and is blithely at his business when an irate cop shows up; in another, two elderly folks from the country bow and pray to a "shrine" that is actually a brightly gaslit newspaper office.

Gaslights were emblematic of the Meiji slogan "civilization and enlightenment," and quite naturally they are the centerpiece of the Gas Museum, which boasts a courtyard illuminated by ornate streetlamps from London, Paris, and the Ginza, the first avenue in Japan to be gaslit from end to end, in 1874. The heyday of gas as a light source was to be short-lived, however, with the introduction of electricity only a few years later. Still, gas remained popular for heating in Japan, as it is to this day. Besides its art gallery and its gaslights, the Gas Museum offers an exhaustive collection of gas-powered lamps, stoves, furnaces, refrigerators, and even a gas-operated pipe organ.

Gas may be the fuel that doesn't get much respect, but in the wake of the electric power industry's nuclear plant disaster, to many Japan residents natural gas might just be starting to smell like a rose.

|

|

A gas streetlamp from Yokohama, the first city in Japan to get gas lighting in 1872. Behind is The House of Gas Lamps, a 1909 building restored and relocated from downtown Tokyo to Kodaira. |

All images courtesy of the Gas Museum |