|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Un-Kawaii Otaku: Makoto Aida at the Mori Art Museum

Alan Gleason |

|

|

Aida Makoto: Monument for Nothing installation view, Mori Art Museum.

Courtesy Mizuma Art Gallery; photo by Osamu Watanabe; photo courtesy Mori Art Museum, Tokyo. |

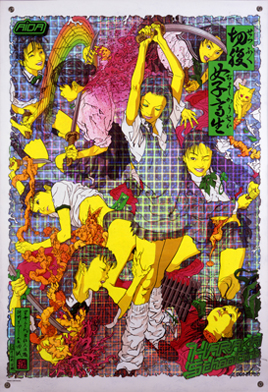

Makoto Aida is the Anti-Cute. His sprawling, unwieldy, downright nasty oeuvre embodies everything antithetical to the Superflat conceits and big-eyed mangaesque indulgences of much of what passes for contemporary art in Japan. That his significance to the discourse has not gone unrecognized was reflected by his inclusion in a show at New York's Japan Society in 2011, Bye Bye Kitty!!! Between Heaven and Hell in Contemporary Japanese Art, which attempted to right the past few years' tilt toward the otaku/kawaii end of the spectrum. A painting Aida displayed there, Harakiri School Girls, has it all -- teenage suicides, the traditional glorification of ritual suicide, the otaku obsession with pubescent girls -- issues that push the buttons of the collective Japanese psyche today. Aida takes fiendish delight in mashing those buttons and holding them down till the viewer screams for mercy. Meanwhile his images -- equal parts nauseating and titillating -- send our synapses firing in corners of the unconscious that we can't even begin to articulate.

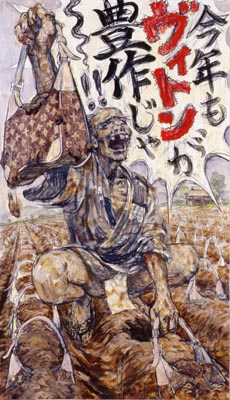

Monument for Nothing, the massive Aida retrospective currently showing at Roppongi's Mori Art Museum, is like a gauntlet the unsuspecting Tokyoite must run for the amusement of a gallery of sadistic Freudian gods. As one advances through the stark, hollow labyrinths of the Mori, the barrage of provocative imagery seems relentless, but is fortunately leavened with plenty of material showcasing Aida's wacky side. A fine example of his canny balance of humor and social commentary is Louis Vuitton, a painting of a filthy, toothless Edo-era peasant triumphantly yanking handbags out of the ground, dirt clods and all, and shouting "Bumper crop this year!" Behind him extend rows of purse straps protruding from the earth like so many vegetables. Not for Aida the cynical commercial tie-ups that masquerade as conceptual art in certain heavily hyped Tokyo circles.

|

|

|

| Makoto Aida, Harakiri School Girls (2002); acrylic on holographic film, 119 x 84.7 cm. Collection of Yasuyuki Watai; courtesy Mizuma Art Gallery. |

|

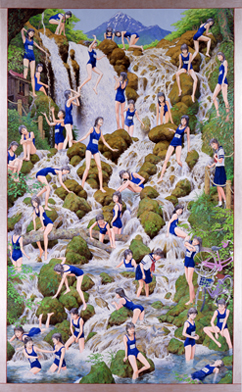

Makoto Aida, Picture of Waterfall (2007-10); acrylic on canvas, 439 x 272 cm. Collection of the National Museum of Art, Osaka; courtesy Mizuma Art Gallery. |

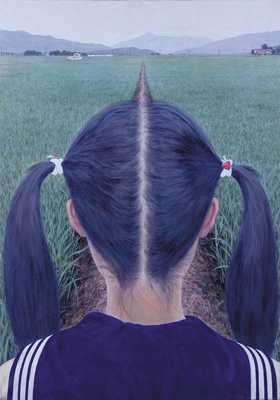

Aida is a consummate parodist. His Azemichi (a path between rice fields) (no longer on view at this show, alas) is a takeoff on the late Nihonga artist Kaii Higashiyama's much-vaunted Michi (The Road, 1950), a simple rendering of a rural road stretching straight toward the horizon. Aida has taken this motif and extended the road from the part in a teenage girl's hair, adding a faintly sinister Lolitesque element to the bucolic scene.

Teenage girls are a recurring motif in Aida's work and probably the most controversial. Aida acknowledges his fixation and even makes fun of it, most blatantly in a video that shows him masturbating (back to the camera, rest assured) in front of a wall with nothing on it but three large Japanese characters, bi-sho-jo, meaning "beautiful young girl." This and other works, some of an even more shocking nature, are sequestered in a small gallery curtained off from the main exhibition, with a sign at the entrance warning visitors of the prurient content within and refusing admittance to anyone under 18. Given the arbitrary and inconsistent behavior of Tokyo's finest in enforcing the nation's anti-pornography laws, this is probably a wise precaution. Oddly, Aida himself practices a sort of self-censorship in depicting his pubescent female subjects. Some are nude, but always nipple-less. Those that are clothed often exude an unadulterated innocence, as in the quite lovely and touching work Picture of Waterfall, which depicts a bevy of girls, demurely clad in their middle-school swimsuits, cavorting around a glorious cascade. Then again, Aida's corrupting effect on the brain is such that every image comes to look suspiciously Freudian.

|

| Makoto Aida, A Picture of an Air Raid on New York City (War Picture Returns) (1996); six-panel folding screens, mixed media, 174 x 382 cm. Takahashi Collection, Tokyo; CG of Zero fighters created by Mutsuo Matsuhashi; courtesy Mizuma Art Gallery. |

Whether the shojo motif is a commentary on the otaku male's so-called "Lolita complex," or merely a venting of the artist's own, is something the viewer is hard put to fathom. In much of Aida's work his methodology seems to consist of tossing the stuff of his subconscious at the canvas, like a plate of spaghetti at a wall, just to see what sticks.

After having one's sensibilities jerked around by the contents of the curtained room, it's a relief to venture back out into the bright open spaces of the main exhibit and enjoy some of Aida's more lighthearted efforts. Even these, however, generally manage to provoke or critique on some level. A gargantuan medieval Japanese castle made of cardboard was inspired, Aida says, by the elaborate dwellings constructed from similar materials by some of Tokyo's more creative homeless. Monument for Nothing IV, a soaring, wall-sized, baby-blue creation that looks vaguely oceanic, turns out on closer inspection to be a mockup of the exploded Fukushima No. 1 nuclear plant, covered with printouts of tweets about the disaster.

|

| Makoto Aida, Monument for Nothing IV (2012); acrylic, paper on plywood, wood bolt, 570 x 750 cm. Courtesy Mizuma Art Gallery; photo by Osamu Watanabe; photo courtesy Mori Art Museum, Tokyo. |

Aida denies that he is a knee-jerk liberal trying to rub our noses in all that is wrong with society, and his feelings about war and patriotism are particularly complex. His War Picture Returns series is inspired by the wartime military government's pressure on Japanese artists to paint scenes of troops in battle and other patriotic motifs. One of his latter-day "war pictures" attracted notice among American viewers due to its eerie confluence with the events of September 11, 2001, though it was painted in 1996. Titled A Picture of an Air Raid on New York City, it shows a formation of World War II-vintage Zero fighters circling in an infinite loop over the skyscrapers of Manhattan, which are ablaze. The reference is clearly to the U.S. firebombing of Tokyo in 1945; whether the image is a tit-for-tat revenge fantasy or a statement about the eternal repetition of history (or, again, both) is hard to say, but it is an understandably disturbing one for New York viewers.

|

|

|

| Makoto Aida, Azemichi (a path between rice fields) (1991); Japanese mineral pigment, acrylic on Japanese paper, 73 x 52 cm. Collection of Toyota Municipal Museum of Art; courtesy Mizuma Art Gallery. |

|

Makoto Aida, Louis Vuitton (2007); oil on canvas, 194 x 112 cm. Private collection; courtesy Mizuma Art Gallery. |

Though the breadth and originality of Aida's artistic visions -- as well as the skill with which he executes them -- are indisputable, his greatest talent may lie in reigning in his more extreme impulses. The lasting impression one gets from the wild and woolly show at the Mori is of his mastery in veering between the high-voltage poles of psychosexual obsession and sociopolitical pontification without quite touching them. His saving grace is what appears to be an utter lack of self-importance. The Japanese subtitle of the show (which I wish they had used for the English as well) translates to "Sorry I'm a Genius." Aida knows perfectly well how pompous that sounds; as he tosses the G-word back at those who have so labeled him, you can practically hear him snickering.

|

|

|

Aida Makoto: Monument for Nothing |

|

Mori Art Museum |

|

17 November 2012 - 31 March 2013 |

|

53F, Roppongi Hills Mori Tower

6-10-1 Roppongi, Minato-ku, Tokyo

Phone: 03-5777-8600 (Hello Dial)

Hours: 10 a.m. to 10 p.m. (to 5 p.m. Tuesdays); admission until 30 minutes before closing. Closed when no exhibitions are being held; check website for schedule.

Transportation: Direct access from Roppongi Hills Exit, Roppongi Station, Tokyo Metro Hibiya Line; 5 minutes' walk from Roppongi and Azabu-Juban Stations, Toei Oedo Subway Line |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for 25 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|