|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Getting Oriented at the Toyo Bunko Museum

Alan Gleason |

|

|

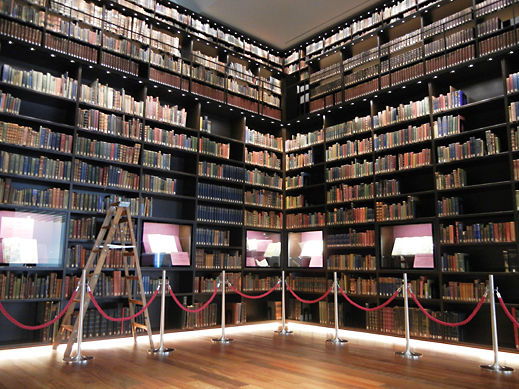

| The Morrison Collection fills a large, high-ceilinged room at the heart of the Toyo Bunko Museum. |

Toyo Bunko, a.k.a. The Oriental Library, is a Tokyo institution that may be better known overseas than in its home country. Japan's oldest and largest Asian studies research library, it ranks with such august entities as the British Library and the Harvard-Yenching Institute and Library as one of the world's top five centers of East Asian studies. Nearly as well-kept a secret is the fact that this singular facility runs a state-of-the art museum whose exhibitions, both permanent and temporary, not only offer access to the library's vast archive of printed materials about East Asia -- many of them in English -- but also provide a detailed look at significant episodes in Japan's history, particularly its encounters with the West.

Toyo Bunko was founded in 1924 by Hisaya Iwasaki (1865-1955), the cosmopolitan third president of the Mitsubishi business conglomerate, to house his personal collection of 38,000 Japanese and Chinese books, expanded in 1917 by his purchase of a 24,000-volume collection of Far East-related tomes owned by George Ernest Morrison (1862-1920), the Australian adventurer who variously served as Peking correspondent for the London Times and political adviser to the republican Chinese government. Occupying an atrium-like chamber of multistory bookshelves that is the museum's centerpiece, the Morrison Collection itself is arguably the most dramatic exhibit on display.

|

|

|

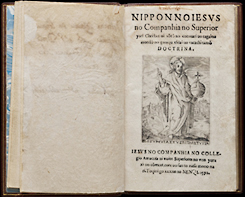

| The title page of Doctrina Christan, a Jesuit text explaining Christian doctrine in romanized Japanese (1592). |

|

A map of Japan by Portuguese Jesuit cartographer Ludoico Teisera, printed in 1595; this is the first map of Japan drawn by a European and possibly the first ever to show the entire archipelago. |

Today the library contains some one million volumes, of which 40 percent are Chinese, 30 percent Western, 20 percent Japanese, and the remainder in such languages as Korean, Vietnamese, Sanskrit, Arabic, and Turkish. The 80-person staff conducts research and assists scholars in their use of the library's stacks, which are open to the public. Among Toyo Bunko's treasures are over 600 inscribed oracle bone fragments from China that date back to the Yin (Shang) period (17th to 11th centuries BCE); 77 editions (54 of them collected by Morrison) of Il Milione, the legendary account by Marco Polo (1254-1324) of his travels in China; and an excellent selection of ukiyo-e woodblock prints, highlighting those that famously influenced 19th-century Western artists like Van Gogh. With so much visually appealing and historically relevant material on hand, it is easy to see why the institute felt the need to augment its library with a museum, which it opened in October 2011.

For the non-Japanese visitor the most fascinating items on display are surely the illustrations of Japan, China and other regions of the "Orient" produced by the first Westerners to visit this part of the world. In Japan these artists range from the Jesuit missionaries who arrived in the 16th century to Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796-1866), a German physician who taught Western science to the Japanese in the final years of the Tokugawa Shogunate and is known for his thorough study of Japanese flora and fauna.

|

|

|

| An illustration of Christians being martyred at Shimabara, Kyushu, from Arnoldus Montanus, Atlas Japannensis, being remarkable addresses by way of embassy from the East India Company of the United Provinces, to the Emperor of Japan (1670). |

|

Kitagawa Utamaro, Takashima Ohisa (1792-93), an ukiyo-e woodblock print from the Toyo Bunko collection. |

Until the end of July, an intriguing special exhibition traces the history of Christianity in Japan, from the arrival of the Jesuits through the religion's rapid spread in Kyushu to its subsequent brutal suppression under the Shogunate. The curious "hook" here is the somewhat tenuous connection between Japanese Christians and Marie Antoinette, of all people. Titled Marie Antoinette and the Noble Ladies of Asia: East West Exchanges through the Culture of Christianity, the show revolves around the guillotined queen's possession of Collected Letters of the Society of Jesus, a 26-volume series of books published in Paris in 1780-83 that describe Jesuit missionary activities around the world. Around the same time, the Jesuits also popularized an account of a samurai wife who converted to Catholicism, received baptism as Gracia Hosokawa, and was killed during the siege of Osaka Castle in 1600. Her execution, allegedly at her own behest, was carried out by a loyal retainer to prevent her being taken hostage by a rival of her husband. Though Gracia died more as a result of the vagaries of civil war than because of her faith, her story was taken up by the Jesuits and she earned posthumous fame in Europe as a paragon of Christian martyrdom in the Orient. The parallels between the two women -- both Gracia and Marie met their demise at age 37 and wrote letters declaring devotion to their Catholic faith and fearlessness in the face of impending death -- prompt the exhibition authors to speculate that Marie may have taken solace from Gracia's example in her own final moments, nearly two centuries later.

|

|

|

| The entrance to the new Toyo Bunko building in Komagome, Tokyo, completed in 2011. Photo by Alan Gleason |

|

The Siebold Garden in the back of Toyo Bunko, with one of its contemporary outdoor sculptures, viewed from the Orient Café. Photo by Alan Gleason

All images courtesy of Toyo Bunko unless otherwise indicated. |

Whatever its historical veracity, this tale of two noblewomen provides an appealing point of entry to the story of Christianity's dramatic rise and fall in feudal Japan, as well as of its perpetuation against all odds by a few faithful -- the "hidden Christians" of the Edo era -- on the more isolated peninsulas and islands of northwestern Kyushu. Maps, photographs, and illustrations -- including some gruesome depictions of the Shogunate's treatment of those who would not renounce their faith -- round out a striking show on a significant episode in pre-modern Japanese history.

For those seeking a change of mood from the sometimes dire subject matter of the Marie Antoinette exhibition, I recommend Toyo Bunko's attractively appointed Orient Café, which looks out on a garden named after the aforementioned Siebold. Also well worth a visit is the nearby Rikugien, one of Tokyo's finest formal gardens.

|

|

|

Marie Antoinette and the Noble Ladies of Asia

Toyo Bunko Museum

20 March - 28 July 2013

|

|

2-28-21 Honkomagome, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo

Phone: 03-3942-0280

Open 10 a.m. to 8 p.m.; admission until 30 minutes before closing

Closed Tuesdays (or the next day when Tuesday is a national holiday) and during the New Year holiday

Transportation: 8 minutes' walk from Komagome Station on the JR Yamanote Line or Tokyo Metro Nanboku Line |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for 28 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|