|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Ishikawa: Not Your Standard-Issue Prefectural Museum

Alan Gleason |

|

|

|

Screen paintings, scrolls, and Old Kutani ware on display in Gallery 2

at the Ishikawa Prefectural Museum of Art |

|

|

|

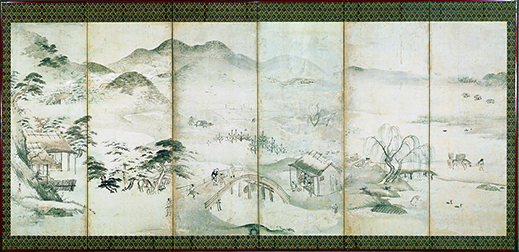

| Kusumi Morikage, Left screen of Farming in the Four Seasons, 17th century, one of two six-panel screens, sumi ink on paper, 146 x 336 cm, Important Cultural Property |

Every prefecture in Japan has its official art museum, showcasing artists of every medium who happened to grow up or study or work in the area. The hodgepodge exhibits that often result tend to make the eyes glaze over, and not every prefecture can boast a critical mass of brilliant art that spurs the out-of-town tourist to explore collections of local talent. A salient exception to the rule is the Ishikawa Prefectural Museum of Art in Kanazawa.

That the Ishikawa's collection should stand out so conspicuously among Japan's regional holdings will come as no surprise to anyone remotely familiar with the prefecture's history. In the words of director Susumu Shimasaki, Ishikawa is "a prefecture whose culture of fine arts and traditional crafts compares with that of Tokyo and Kyoto." That claim is no overstatement. Thanks to the artistic tastes and fiscal largesse of the wealthy Maeda clan who ruled the area (then known as the Kaga Domain) from 1583 to 1868, Ishikawa Prefecture, and Kanazawa in particular, has long boasted a cultural legacy rivaling that of Japan's capitals, current and former.

|

|

|

|

|

|

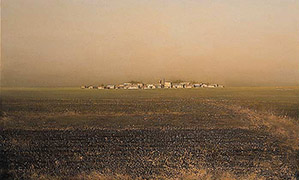

| Nihei Morimoto, Earth and Colony (1995), oil on canvas, 88.3 x 144.4 cm |

|

Yoichiro Nishida, View for the Realm of Line (1992), acrylic on canvas, 170 x 200 cm |

The present Ishikawa Museum opened in 1983, but its predecessor, founded in 1959, was one of Japan's oldest regional museums. Attractively laid out on a wooded hilltop next to Kanazawa's legendary Kenrokuen garden, the building is a rambling affair with several large exhibition rooms. One of these features works in the possession of Maeda Ikutokukai, a nonprofit foundation tasked with preserving the cultural artifacts of the Maeda family, among them a glorious screen painting by the sumi-ink master Sesshu (1420-1506). The museum itself owns a lovely double-screen ink painting, Farming in the Four Seasons, by Kusumi Morikage (c.1620-90), a Kano-school artist who deviated from conventions of the time to depict the everyday lives of farmers and the rural poor. Ceramics buffs will want to visit the Ishikawa for its extensive collection of Kaga's Old Kutani ware, famed for its thick overglazes and bold designs and colors.

But while the museum's collection of Edo-period masterpieces -- the Maeda heritage -- is second to none, what astonishes is the quality of the more contemporary work on display. It turns out that 20th-century Ishikawa Prefecture was a hotbed of Western-influenced experimentation, thanks in part to the influence of locally born painter Saburo Miyamoto (1905-74), a master of Western-style realism. Regional artists followed in his footsteps, an example being Nihei Morimoto (1911-2004), whose subdued, ochre-hued yet luminous landscapes recall Andrew Wyeth. More recently, postwar favorite sons like Yoichiro Nishida (b. 1948) and Koichi Hiraki (b. 1958) have produced a slew of surrealistic works -- some hilariously absurd, some downright gorgeous -- that make one wonder just what's in the water in Kaga. It is to the museum's credit that it continues to champion regional art that bears little if any link to the glories of the Maeda days, other than in its level of accomplishment.

|

|

| Koichi Hiraki, Three Invisible Sounds (2004), oil on canvas, 184 x 460 cm |

|

|

|

| Yoshifumi Nojima, Market of Affectation (2000), 486 x 130 cm, oil on gesso and panel, collection of the artist |

In addition to rotating displays from its permanent collection, the Ishikawa highlights individual artists in special exhibitions, as it did recently for the remarkable and deserving-of-wider-recognition painter Yoshifumi Nojima (b. 1948). Born in neighboring Toyama Prefecture (also part of the old Kaga Domain), Nojima graduated from the Kanazawa College of Art, then spent three years at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent, Belgium, where he became absorbed in mastering the "Flemish technique" of oil painting. Developed by artists like van Eyck half a millennium ago, this was one of the earliest methods of working with oil, either in combination with or in place of tempera. Transparent glazes are layered several times over a white gesso ground, producing a glow so luminous that, as Nojima surmises, viewers "are tempted to search for the light projector hidden behind the painting."

In Yoshifumi Nojima - Evolution from the 15th Century Flandre Technique (which closed on November 17 after a too-short month's run), Nojima's large oils hung in a darkened gallery whose walls were covered with black cloth, a single spotlight illuminating each work. Nojima was not exaggerating: the paintings gleamed as if backlit.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yoshifumi Nojima, Wind Erosion G (2006), F130, oil on gesso and panel,

collection of the artist |

|

Yoshifumi Nojima, Wind Erosion - Pumpkin F (2010), S100, oil on gesso and panel, collection of the artist |

A devotee of Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516), Nojima spent much of his time in Ghent painting copies of such works as Hell and the Flood and St. Jerome at Prayer. In his first years back in Japan, he produced paintings that emulate Bosch's distinctive mix of the whimsical and the grotesque. Sometime around 2007, however, Nojima appears to have become obsessed with painting huge close-ups of kabocha pumpkins that he has allowed to dry and shrink over a period of several years. Into the cracks and orifices of these mummified vegetables he inserts bizarre objects: gears and other mechanical devices, fossils, insects, and organic blobs that resemble entrails. The results are some of the most quease-inducing still lifes you will ever encounter. And indeed, Nojima declares that they are inspired by the same sense of existence's absurdity that "Roquentin felt when he saw the roots of the chestnut tree in Sartre's Nausea."

Their disturbing appearance notwithstanding, Nojima's pumpkins gleam with the shimmering beauty of a Flemish masterpiece. Working today at the peak of his craft, he is living proof that the artistic legacy of Kaga shines brightly on.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yoshifumi Nojima, Wind Erosion - Pumpkin M (2011), F130, oil on gesso and panel,

collection of the artist |

|

Yoshifumi Nojima, Wind Erosion - Pumpkin UC (2012), F200, oil on gesso and panel, collection of the artist

All images are courtesy of the Ishikawa Prefectural Museum of Art. |

|

|

|

Ishikawa Prefectural Museum of Art |

| |

2-1 Dewa-machi, Kanazawa City, Ishikawa Prefecture

Phone: 076-231-7580

Open 9:30 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. (last admittance 5:30 p.m.). Open all year, but exhibition galleries are closed during the year-end and New Year holiday.

Transportation: Located next to Kenrokuen garden; 15 minutes by Kenrokuen shuttle bus from JR Kanazawa Station to Seisonkaku-mae bus stop. |

|

|

|

|

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for 28 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|