|

|

| Till Nowak, The Experience of Fliehkraft (2011) |

At last: a cutting-edge, multimedia art show with plenty of visual wackiness that even little kids -- or Luddite adults -- can "get"!

Come to think of it, maybe most "media art," leaning as it does toward experimental and often irreverent applications of the latest gee-whiz communications technology, is both cutting-edge and wacky to some extent. In any case, Open Space 2013, on till March 2 at the NTT InterCommunication Center (ICC) in Hatsudai, Tokyo, offers plenty of guffaw opportunities as well as a number of works at the sublimely contemplative end of the scale. Yet the show (described by ICC as a "beginner's guide to media art") is compact, the number of exhibits not overwhelming -- and utterly wholesome and suitable for family consumption.

As is often the case, no doubt for cultural reasons I don't even want to try to figure out, the non-Japanese works in this international show seem more laugh-out-loud funny, more deliberately entertaining, than the somewhat abstract, Zen-y contributions by many of the domestic artists. Here are a few examples:

By far the most in-your-face satirical piece is Hamburg-based Till Nowak's The Experience of Fliehkraft. A video pseudo-documentary featuring physically untenable amusement park attractions and the mad scientist who conceived them, the work is a hilarious sendup of human technological hubris. The "rides," brilliantly created with computer graphics juxtaposed with footage and sounds of actual amusement-park crowds, run at speeds that would kill riders in real life, or alternatively, bore them to death (a 14-hour ferris wheel!). In an "interview," their inventor, who is studying "the effects of centrifugal force on the human brain," acknowledges that "a few mistakes" were made in the early stages . . .

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gregory Barsamian, Juggler (1997). Photo by Takashi Ohtaka |

|

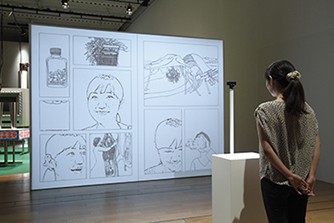

Nova Jiang, Ideogenetic Machine (2011) |

Equally entertaining is New Yorker Gregory Barsamian's Juggler, a room-sized rotating strobe sculpture that conjures up the very realistic illusion of humanoid figures juggling objects that mutate, before one's eyes, from phone receiver to milk bottle to milk to dice to dog bone (which descends under a tiny parachute!), and back to a receiver. Barsamian cites the influence of Jungian psychology -- dream images and archetypes -- but the work can simply be appreciated as pure fun by visitors of all ages.

A more interactive presentation, Los Angeles-based Nova Jiang's Ideogenetic Machine, employs a camera to capture the viewer's face and inserts it here and there amid frames of a wordless, somewhat surreal cartoon story prepared by the artist. The result is the viewer's very own manga, featuring him or her as the protagonist, which can be acquired via email and augmented with dialogue to the owner's taste.

Closer to the realm of pure art are works like Swiss-born Pe Lang's moving objects. This deceptively simple construction of tiny plastic rings strung on thin, horizontal silicon tubes comes alive when, at the touch of a button, the tubes begin to vibrate, causing the rings to jiggle back and forth, colliding and separating in patterns that are at once random and dictated by the laws of physics. The result is a painting that pulses and circulates -- hypnotic, meditative, and somehow touching in the way it imparts organic movement to inorganic components.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Pe Lang, moving objects no. 692 - 803 (2012) |

|

Ei Wada, Toki Ori Ori Nasu ver.2: Falling Records (2013) |

Similarly striking for the beauty it elicits from prosaic moving parts is Ei Wada and his group Open Reel Ensemble's Toki Ori Ori Nasu ver.2: Falling Records, an installation of four open-reel tape recorders mounted in parallel high up on a wall. From each machine a single reel of tape unravels downward, dropping like a waterfall to the bottom of a backlit acrylic shaft, where the tape accumulates in ever-mutating loops. When the tapes come to an end they abruptly rewind back up onto the reels, emitting a speeded-up version, in slightly phased unison, of the music recorded on them (on the day I visited they were playing The Blue Danube). Again, randomly generated patterns of familiar materials -- in this case, the piling, shifting loops of tape -- induce a pleasingly trancelike state.

But the prize for sensory stimulation must go to the anechoic chamber created by Japanese sound artists evala and Akio Suzuki. Named for the African bat-eared fox, which is known for its acute sense of hearing, Otocyon megalotis offers a truly psychedelic experience. The visitor sits in the middle of a box-like room devoid of light or sound, surrounded by a matrix of eight equidistant speakers (plus one more under the chair). For ten minutes you are bathed in an onrush of unexpected sounds -- some soothing, some jarring -- that seem to inhabit your head, perhaps even emanate from it. The experience is a powerful lesson in the close link between aural and visual perception. Deprived of sight, the mind loses any sense of the distance between itself and the sound source. A number of aural-trip options are offered, ranging from handmade musical instruments to the sounds of nature. Since only one person can sit in the chamber at a time, it's a good idea to reserve a time slot for yourself when you first enter the exhibition.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Toshio Iwai, Marshmallow Scope (2002) |

|

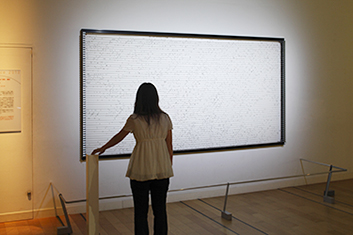

Yasuhiro Suzuki, Footprint of Your Future (2009)

Photos are by Keizo Kioku unless otherwise noted. All images are courtesy of NTT InterCommunication Center (ICC). |

Leavening the intensity of installations like the above are some very light-hearted works. Hits with the younger set include Toshio Iwai's Marshmallow Scope, which functions like a temporal funny-mirror that distorts, in time, the movements of anyone passing in front of the video camera hooked up to the monitor; and Yasuhiro Suzuki's Please Watch Your Time and Footprint of Your Future, which respectively reproduce your face on the hands of a wall clock, and your footsteps as footprints on the floor -- ahead of you, before you take them.

NTT, the telecom behemoth, has been presenting Open Space at its ICC site in Tokyo Opera City since 2006. Neither daunting in scale nor overly hyped, the show does a nice job of organizing media-art installations -- with their potential for sprawl -- in a space that is easy to negotiate and far less exhausting than big-ticket, kitchen-sink events like the gargantuan Cultural Agency-sponsored Japan Media Arts Festival (slated for next month; for a review of last year's edition, see the February 2013 issue of Here and There). The curators have also reached out to non-Japanese visitors by preparing a well-written English pamphlet describing each work in detail. Some of the pieces are more successful than others at inspiring the viewer, but few will disappoint, and the overall playfulness quotient will leave you refreshed and rejuvenated. Bring the kids!

|

|

|

Open Space 2013 |

|

NTT InterCommunication Center (ICC) |

|

25 May 2013 - 2 March 2014 |

| |

Tokyo Opera City Tower 4F, 3-20-2 Nishi-Shinjuku, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo

Phone: 0120-14-4199

Open 11:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Closed Monday (or Tuesday when Monday is a holiday) and 9 February (maintenance day)

Transportation: 2 minutes' walk from Hatsudai Station (east exit) on the Keio New Line, one stop west of Shinjuku Station |

|

|

|

|

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for 28 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|