|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Where There Is Light -- at the Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura

Alan Gleason |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Viewed from the museum terrace, the torii at the entrance to Tsurugaoka Hachiman Shrine looms behind Heike Pond, with the hills of Kamakura in the distance. Photo by Susan Rogers Chikuba |

|

The upper floor of the museum, supported by rusted-steel columns, extends over the pond. In the background, gardeners arrive by boat to tend to some island landscaping. Photo by Susan Rogers Chikuba |

Like such glib dualisms as life and death, or love and hate, "light" and "place" are two words that get bandied around to excess by people writing about art. Pretty much all art references some universal theme or other -- and of course, all art reflects, absorbs, plays with, and depends on light. So From the Collection: Where There Is Light (the Japanese title, Hikari no aru tokoro, translates literally as "a place where there is light"), the current show at the Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura, could be about practically anything. But I'm a sucker for art that highlights light, and that was the magic word that drew me to the exhibition, which promised an assemblage of works focusing on "the emergence of light."

Normally I'm also wary of exhibitions culled "from the collection." Such shows often seem to be a way for museums to tread water while gearing up for a really big event a few months hence. The bad news about the Kamakura show is that it does have a kitchen-sink aspect that makes it difficult to discern a unifying theme. The good news is that the museum happens to boast a fine collection of post-Meiji-Restoration art, particularly of the prewar yo-ga ("western-style painting") and postwar avant-garde genres. With only some 80 works on display, all but a dozen of them paintings or woodcuts, this is a gratifyingly succinct retrospective of modern Japanese art.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hanjiro Sakamoto, Landscape with Hemp Palms (1903), watercolor on paper, 50.0 x 66.5 cm |

|

Yuichi Takahashi, Enoshima (1876-77), oil on canvas, 47.2 x 74.2 cm |

One enters the first and largest gallery to confront a roomful of yo-ga from the Meiji era. This does not seem too auspicious, though the work facing the door, a pleasant rural landscape by Hanjiro Sakamoto titled Landscape with Hemp Palms (1903), lives up to the show's billing with a soft, mellow light in an impressionist mode. Other works like Nojima's Cottage, Atami (1933) by Ryuzaburo Umehara shine a Provence-like sun on scenes that feel glowingly subtropical, as Japan often does in the summer.

One of the pleasures of Japanese art from this period is the window they open onto life and lifestyles in those days of cultural transition. Yuichi Takahashi's Enoshima (1876-77) lovingly depicts families, priests, and peddlers strolling across the sand spit to the titular island (a Kamakura-area tourist destination that remains just as popular today).

|

|

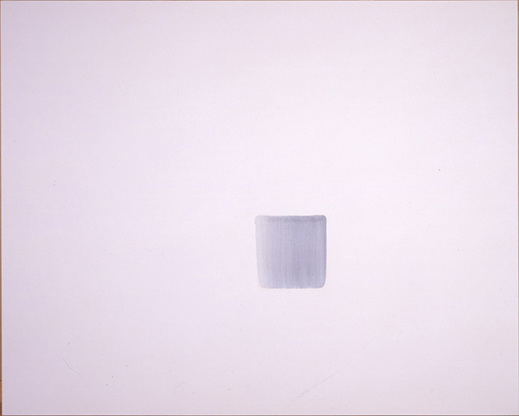

| Lee Ufan, Correspondence (2003), color on canvas, 181.6 x 227.3 cm |

Most of this first section, which extends only to 1936 but makes up more than half of the exhibition, consists of figurative paintings, with a few stabs at cubism and some surrealist pieces from the thirties for good measure. Few seem to showcase any pronounced use or effect of light, so one is left a bit befuddled about the selection process. The next gallery, which picks up in 1957 after the long interregnum of the war, shifts abruptly to big abstract-expressionist works. With their penchant for expanses of unpainted canvas, artists of this era were arguably more engaged in conscious experiments with light -- or the utter lack thereof. Indeed, the most compelling piece is almost entirely black: Masanari Murai's People at the Waterside (1964), a massive composition of thickly slathered oils in varying shades of black, punctuated by a number of tall, thin, curved gray rods -- no people or watersides in sight. More typical are Lee Ufan's Correspondence (2003) and Natsuyuki Nakanishi's Shape and Shadow of an Arc (1980), both studies in white -- though again, it's hard to see how light is more involved here than in, say, planetary life as we know it.

Where the show truly comes to life, and justifies its title best, is in the ground-floor sculpture gallery, a space that extends from the building's inner courtyard onto a terrace that juts out over a pond. The gallery walls are made of Oya stone, an off-white igneous rock whose rough, warm texture perfectly sets off the contemporary works on display. These sculptures, which make up the remainder of the show, inspire with the creative ways they utilize and transform the outdoor light that bounces off the pond or pours into the courtyard.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Natsuyuki Nakanishi, Shape and Shadow of an Arc (1980), oil on canvas and bow, 193.4 x 111.7 cm. Photo by Tadasu Yamamoto |

|

Rei Naito's, Grace (2009 [1999-]), beads and line, 260 x 550 x 0.15 cm. Photo by Naoya Hatakeyama |

At once the most luminous and most delicate work is Rei Naito's Grace, a simple parabola of tiny glass beads strung from the eaves over the pond. On what was the Kanto area's first springlike day this year (talk about perfect timing!), the bright sun was put to excellent effect as Naito's necklace of light shifted patterns beneath the shadows of passing clouds. The only thing missing was a breeze to swing the beads back and forth.

Judging by their use of Grace to represent the "Light" exhibition in brochures and publicity materials, the curators recognize it as a key asset. But in fact, Naito's contribution to this show was something of a disappointment. Her profoundly moving solo exhibition in this same space in 2009-2010 (covered here by this column) was a tour-de-force of light and darkness, and it was her name more than anyone else's that prompted high expectations for the current show on my part. Grace was featured in the previous show, too, but only as one part of her presentation -- in fact, the bead parabola was itself one component of a larger installation. This time it is paired with a work of hers from 2009, The Spirit (Please Be with Me), which consists of two tiny smiley-face-like buttons embedded side by side in a crevasse in the Oya-stone wall. Naito's work often displays a streak of childlike whimsy; when it works, it can be downright mystical, but when it does not it risks looking trivial, as this piece does.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Rei Naito, The Spirit (Please Be with Me) (2009), buttons (private collection) installed in Oya stone. Photo by Naoya Hatakeyama |

|

Noe Aoki, Water in the Air - 1 (2007), iron, 201.0 x 73.0 x 73.0 cm |

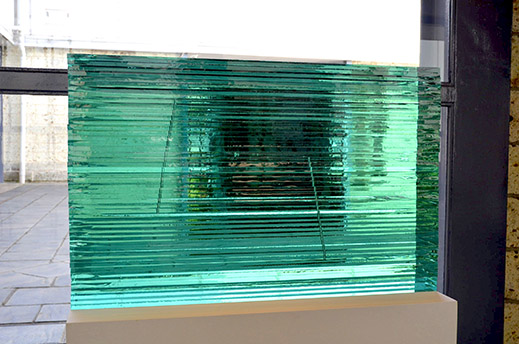

Though the show could have benefited from a more substantial presence by Naito, the other sculptures include some gems. Noe Aoki's Water in the Air - 1 (2007), a remarkably lithe work in iron of droplet-like circles that form thin vertical rods, truly brings to mind a fluid medium that solidified and rusted in place as it fell from the sky. Perhaps the loveliest piece is the oldest in this section: Megu, created by Aiko Miyawaki in 1972. This translucent blue-green block, about a meter long and half a meter high, is a stack of horizontal layers of glass that refract incoming light every which way. Accenting the angular shifts in the light flowing through it are two embedded sequences of solid-colored plugs, aligned almost but not quite atop each other. The result is two incrementally curving forms that resemble strands of seaweed waving underwater, breaking up the monolithic field in the most sublimely minimal way conceivable.

Only an hour by train from downtown Tokyo, Kamakura is a beautiful town with temples and shrines to rival Kyoto's. And the museum is in a prime location on the precincts of the city's centerpiece, Tsurugaoka Hachiman Shrine (the pond looks across to the shrine's vermilion torii gate and bridge, as well as to islets tended by gardeners in rowboats). Backed by green hills and opening onto Sagami Bay, Kamakura is blessed with rolling terrain, sea breezes, and southern light -- an ideal locale for an exhibition about "light" and "place." Perhaps the curators were on to something after all.

|

|

Aiko Miyawaki, Megu (1972), glass, 57.0 x 90.0 x 20.0 cm (installation view at the Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura, February 2014)

All photos courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura & Hayama, except where otherwise noted. |

|

|

|

From the Collection: Where There Is Light |

|

The Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura |

|

14 December 2013 - 23 March 2014 |

| |

2-1-53 Yukinoshita, Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture

Phone: 0467-22-5000

Hours: 9:30 a.m. - 5 p.m. (last admission at 4:30 p.m.)

Closed Monday (except for holidays), during preparation periods between exhibitions, and 29 December - 3 January

Access: 10-minute walk from Kamakura Station (JR Yokosuka Line or Enoden Line), on the grounds of Tsurugaoka Hachiman Shrine |

|

|

|

|

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for 28 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|