|

|

| A row of refurbished Ogawa sake storehouses, viewed from the Seta riverfront in Kawasaki, Ise. Photo by Alan Gleason |

Ise is justly renowned for the ancient shrine by the same name, sanctuary of the sun goddess Amaterasu. Less frequented by tourists are the neighborhoods that historically provided logistical support to the throngs of visitors to the shrine, particularly during the Edo period (1603-1867), when a pilgrimage to Ise was one of the few excuses for out-of-town travel permitted to commoners by the draconian Tokugawa Shogunate.

|

|

| Kawasaki as it appeared in the early Taisho era (1912-26), from a colorized picture postcard. |

As in other parts of Japan, recent years have seen a gratifying proliferation of efforts to restore some of these old districts, and Ise can lay claim to one of the most successful of such projects in Kawasaki, a neighborhood known in its heyday as the "kitchen of Ise." Situated along the Seta River, a navigable waterway that meanders through the mud flats between the city center and Ise Bay, Kawasaki was where local wholesalers built warehouses to store the sake, foodstuffs, and other goods that arrived by boat from all over Japan. A critical mass of these structures -- fine representatives of tsumairizukuri architecture, a style unique to Ise -- miraculously escaped wartime bombings, urban renewal, and other vagaries of the modern era. Still, by the 1980s these buildings had fallen into considerable disrepair. With freight trains and then trucks replacing the riverboats, Kawasaki's warehouses were boarded up and abandoned, though descendants of the old merchant families could still be found living in their homes nearby.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Copper-covered windows on the street side of an Ogawa warehouse. The façade is made of cedar. Photo by Alan Gleason |

|

A typical Kawasaki storefront, still in business as a grocery. Photo by Alan Gleason |

The impetus for restoration of Kawasaki arrived in the form of a threat: a devastating flood in 1974 prompted the conversion of the Seta River into a concrete-lined canal, and with it plans to dismantle the now-obsolete warehouses. A citizens' movement to save Kawasaki was launched in 1979, and the ensuing campaign to preserve the buildings and revitalize the neighborhood has succeeded magnificently.

The restoration project extends for nearly a kilometer along a narrow lane one block back from the riverbank. The centerpiece is the Ise Kawasaki Shoninkan (Merchant Hall), which sprawls across 1,000 square meters on both sides of the street. Restored by the city of Ise and designated by the government as a Registered Tangible Cultural Property in 2001, the complex reopened in its present incarnation in 2002 and is managed by Ise Kawasaki Machizukuri-shu (People Building the Town of Ise Kawasaki), an NPO formed in 1999.

|

|

| A Meiji-era sketch of Kawasaki, with a somewhat alphabet-challenged English caption. Photo by Kaoru Moriyama |

Between the street and the river sits a row of warehouses, beautifully maintained examples of the distinctively gabled tsumairizukuri style with their dark-brown latticed cedarwood facades, white trim, and ornate tile roofs. These were where the Ogawa family stored its sake barrels. Several of the structures have been joined into a single large, high-ceilinged space that houses a warren of craft and clothing shops. Down the street are a café, a design workshop that features Ise Shunkei lacquerware, and a small building, modeled after one of the old streetcar stops, that now serves as a pier for boat trips down the Seta. Farther along are still more cafés and restaurants, all occupying renovated Edo- or Meiji-era buildings.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| An Ogawa roof tile, prominently displaying the family's signature "X" crest (a modernization of the traditional "crossed hawk feathers" insignia shown above). Photo by Kaoru Moriyama |

|

Roof tiles atop one of the Ogawa warehouses with the same "X" crest. Photo by Alan Gleason |

The main attraction, however, is across the alley: the main Ogawa residence (the family lived there until the 1980s), a spacious edifice that boasts a museum as well as two tranquil Edo-era gardens and a tea ceremony room modeled after that of the master Sen no Rikyu. The museum exhibits dovetail nicely with the sights one sees wandering along the alleys just outside the door. A significant part of the display is devoted to the heavy roof tiles, decorated with family crests, wave-like sculptures, and demonic faces, that adorn these houses.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Entrance to the Ogawa kura storehouse inside the Ise Kawasaki Shoninkan. Photo by Alan Gleason |

|

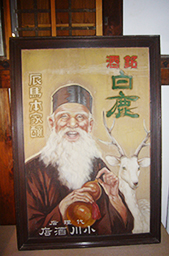

A Meiji-era poster for Ogawa sake. Photo by Kaoru Moriyama |

Also of interest are artifacts from the Ogawa family business, which expanded from sake into cider production in 1909; it continued to sell its flagship "S Cider" (the initial is a tribute to Ogawa patriarch Sansaemon) into the late 1970s. Now the NPO has teamed up with the Kadoya company to bring the brand back to life, retro labeling and all. (I can testify that it's delicious!)

Given that the sanctuaries of Ise Shrine itself are famously replaced every 20 years, it is all the more impressive that the old wooden buildings of Kawasaki have weathered the winds of change so well. Although Japan has plenty of shiny new Disney-like replications of old neighborhoods -- the Okage Yokocho shopping complex just outside the shrine gate is an example -- Kawasaki is the real deal, and the folks at the NPO who serve as its vigilant guardians deserve our gratitude and patronage.

|

|

Another Ogawa sake warehouse inside the Shoninkan complex. Photo by Alan Gleason

All photos are by permission of the Ise Kawasaki Shoninkan.

|

|

|

Ise Kawasaki Shoninkan |

|

2-25-32 Kawasaki, Ise City, Mie Prefecture

Phone: 0596-22-4810

Hours: 9:30 a.m. - 5 p.m. Closed Tuesday (or Wednesday when Tuesday is a national holiday)

Access: 15-minute walk from Iseshi Station (JR Sangu and Kintetsu Yamada Lines), 1 1/2 hours from Nagoya |

|

|

|

|

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for 28 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|