|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spiritual Worlds at the Photography Museum

Alan Gleason |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Naoki Ishikawa, "Mt. Fuji #28" (2008). |

|

Risaku Suzuki, "Between the Sea and the Mountain - Kumano 14" (2005). |

As art-show themes go, "spirituality" is sort of a no-brainer. Art is, after all, expected to be a direct conduit to the soul, and for many of us the craving for a bit of spiritual uplift, maybe even the occasional satori-like epiphany, is what draws us to museums and galleries. In terms of content, Western art has always been heavy on Biblical scenes and overtly religious themes in general. What, then, might an exhibition of photographic art about spirituality, Japan-style, entail?

Tetsuro Ishida, curator of The Spiritual World at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, writes in his catalog essay that he selected works from the museum's permanent collection that "portray aspects of religion and folk beliefs in Japan." Thus the emphasis is a fairly literal one, on images depicting faith and its temporal manifestations: shrines, temples, Buddhas, shamans and worshippers, holy mountains and waterfalls. Many of the pictures, particularly those of people in prayer or trance, are movingly evocative of the state of communion with the spiritual world. But in a country where that world has always been far more immanent than transcendent -- inhabiting not only ourselves but our immediate surroundings, rather than dwelling in heaven on high -- one might expect a bit more attention to the rich vein of photography here that seeks to actually reproduce, or at least represent, the spiritual experience.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Shomei Tomatsu, "The Pencil of the Sun, Iriomotejima" (1972). |

|

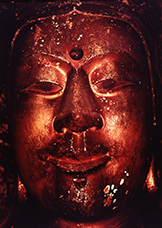

Ken Domon, "Face of the Yumedono Avalokiteshvara (Bodhisattva of Compassion), Horyuji Temple" (1972), from A Pilgrimage to Ancient Temples. |

For me, the high points of the show were precisely those images that inspired awe and even gratitude -- for life, for the vast incomprehensible cosmos, for being born an at least somewhat sentient being. Among the standouts were Ken Domon's mesmerizing closeups of the astonishingly lifelike faces of statues of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, taken on his sojourns to temples throughout Japan. Shomei Tomatsu's monochrome shots of female shamans in Okinawa offered glimpses into a separate, yet also non-separate, reality with unsettling hints of sorcery. Perhaps the most disarming images were those of sightless mediums in northeastern Japan, taken by Masatoshi Naito in the 1960s. The elderly women are sometimes captured in mid-trance or -dance, but just as often they grin effusively at the camera.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Masatoshi Naito, "Old women spending night at the shrine, Takayama-Inari, Aomori" (1970), from Old Women in a Burst! |

|

Hiromi Tsuchida, "Ise Jingu Bugaku, Ise, Mie" (1987), from ZOKUSHIN: Gods of the Earth, Continued. |

In tackling a theme this broad and amorphous, particularly when one has access to a collection as vast as this museum's, any curator would be hard put to pare the display options down to something manageable. Ishida has wisely divided this show into two parts with different approaches. The first half comprises a number of theme-based sections (Sanctuary, Immortality, Kami and Buddhas, To the Invisible), while the second is a series of galleries devoted to specific artists. Inevitably, however, the show's center of gravity tilts toward the latter, and here we are at the mercy of the curator's own tastes in choosing who to give star treatment and who to relegate to the crowded "theme" sections. I wanted very much to see more of Domon's Buddha portraits (only four appeared here), and would have settled for less than a roomful of Tadanori Yokoo's "technamation" lightbox paintings of crucifixes and angels against a backdrop of animated waterfalls. Then again, Yokoo's works were the only ones referencing the Western religious-art tradition, which made for an edifying contrast with the rest of the exhibition.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tadanori Yokoo, "All for One, One for All" (1993). |

|

Tokihiro Sato, "Photo-Respiration: From the Sea, #347 Hattachi" (1998).

Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography |

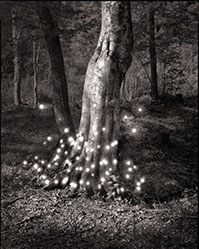

Though The Spiritual World did include some landscapes that offer balm for the soul by simply recording Nature at her most sublime -- notably a gallery devoted to Mt. Fuji, and works like Risaku Suzuki's Between the Sea and the Mountain, of a forest trail overlooking the ocean in the Shinto holy land of Kumano -- a more intuitive articulation of mystical experience could be found in another exhibition the museum is showing concurrent with this one. Sato Tokihiro: Presence or Absence showcases a remarkable body of work by one of Japan's most innovative and inquisitive artists working in the photo medium. Born in 1957 in Yamagata, Sato began his career as a metal sculptor, and even after turning to the camera in the late 1980s, he has always engaged himself with issues of space and depth. This show focuses mostly on his long-term Photo-Respiration project, which gives full play to his fascination with such assertively non-digital elements as 8 x 10 film and extremely long exposures. In the three series "From the Sea," "In the Snow," and "Trees," he sets up his camera in natural environments, opens the lens, then moves about with a mirror (by day) or a penlight (by night), creating glowing spots or lines of light that populate the landscape or seascape like so many wood sprites, water nymphs, or will-o-the-wisps. Most amazingly, no trace remains of Sato himself in these prints: nary a shadow nor a footprint registers, due to the lengthy exposure times.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tokihiro Sato, "Photo-Respiration: Trees, Shirakami #7" (2008).

Collection of the artist |

|

Tokihiro Sato, "Wandering Camera 2, Musenyama #1" (2013).

Collection of the artist

All images courtesy of the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography. |

Though Sato's concerns appear to be primarily technical and aesthetic, the images he produces are nothing if not mystical. Indeed, of all the photographs I saw in the course of viewing these two shows in the same afternoon, Sato's supernaturally luminous forests and seashores seemed the most profoundly imbued with spiritual energy. And for photo buffs for whom a little spirituality goes a long way, his other series on display -- shot with a homemade camera obscura which he towed around Japan behind his car, or with pinhole cameras of various permutations, including a room converted into one big camera -- testify to the delight he takes in forging new pathways in photography, both as technology and as art.

|

|

|

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for 28 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|