|

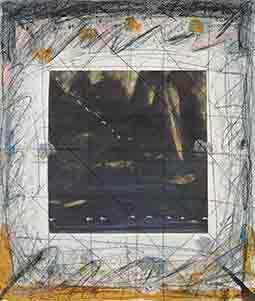

Ichi (1995), ink on paper |

On first hearing, an exhibition consisting largely of variations on the Kanji character  , the number one (pronounced ichi), sounds like it might be, well, a tad minimalist. But Yusaku Tawara's "one" is anything but a simple concept. Each rendering is truly a work of art that rewards lengthy contemplation and repeated views. , the number one (pronounced ichi), sounds like it might be, well, a tad minimalist. But Yusaku Tawara's "one" is anything but a simple concept. Each rendering is truly a work of art that rewards lengthy contemplation and repeated views.

The retrospective of Tawara's work on display until February 8 at the Nerima Art Museum in western Tokyo offers much more than single horizontal strokes of sumi ink. Tawara (1932-2004) was a mystic, concerned with giving visual expression to the ineffable essence of the cosmos. About his favorite numeral, he said: "Ichi is not just the number one or the beginning of something; on the macro level it is the entire universe, and on the micro level it is the wave that is the smallest unit of reality."

|

Ichi (1996), ink on paper |

|

Ichi (2001), ink on paper |

Hado -- meaning a wavelike movement, or fluctuation -- was a word Tawara favored to describe what he perceived as the fundamental element of both natural and spiritual phenomena. In his way he treaded a path similar to that of thinkers who in recent decades have sought to find common ground between Eastern philosophy and modern science, a la the "Tao of physics." And indeed, Buddhism was a powerful influence on Tawara's life and art.

Born in Onomichi, Hiroshima Prefecture, Tawara showed artistic promise at an early age and apprenticed himself to Western-style painter Wasaku Kobayashi while in high school. Entering university in Tokyo, he dropped out to concentrate on art after an oil of his won the Prime Minister's Prize in a competition. That was in 1951; for the next decade he devoted himself to painting oils like the intense, thickly slathered Still Life from 1957, which juxtaposes a fish and a pear in spare Zenlike fashion.

|

Still Life (1957), oil on panel |

Then, in 1963, he abruptly quit painting, for reasons he never explained. For 25 years he worked at Bingoya, a folkcraft shop he ran with his brother in Tokyo, and earned a reputation as a collector and curator of traditional crafts, particularly clay dolls. Along the way he became close to textile designer Keisuke Serizawa and other members of the Mingei folk-arts movement.

In 1987, Tawara resumed painting -- but this time with sumi ink, not oil. During the final decade of his life he was astoundingly prolific in this medium. One year he devoted himself to producing ten tiny postcard-size sumi works a day, for a total of 3,650, many of which he mailed to family and friends. A few dozen of these are on display at the Nerima.

Auspicious Cloud Mandala (2002), ink on paper |

|

Space (2002), ink on paper |

During this period and posthumously, Tawara gained more recognition overseas than he did at home, beginning with an exhibition in London in 2000. In 2012, eight years after his death, the Indianapolis Museum of Art produced his U.S. debut, Universe Is Flux: The Art of Tawara Yusaku, which went on to the Asia Society in Houston in 2013. The current presentation is essentially the same show -- the first major exhibition of the artist's work in his home country.

|

Cloud Mandala (2002), ink on paper |

Though Tawara's late-period output was prodigious, it is not the quantity but the quality of his work that inspires awe. Every painting, large or small, offers food for thought, and a bit of an epiphany. His Buddhist motifs range from a series of purely abstract images titled "Nirvana" to mandalas that display arrays of cloudlike brushstrokes in place of Buddha figures. The cloud motif, which he referred to as "auspicious clouds" (zuiun), is really a more rounded variant of his "one" stroke: a single, elliptical, counterclockwise swipe of the brush that trails off to the bottom right, looking a bit like the capital letter Q, or perhaps a tadpole. He was also fond of waterfalls, mountains, and ocean waves, drawing inspiration from the Song-dynasty masters of sumi landscape art. But these nature-evoking images so brilliantly straddle the spectrum between figurative and abstract that they become a sort of Rorschach test of our own aesthetic inclinations.

|

|

Thinking of Ancient Paintings (1997), ink on paper |

|

|

|

|

|

Prayer (1988), ink and color on paper

All works shown are by Yusaku Tawara; images are courtesy of the Nerima Art Museum.

|

Even Tawara's seemingly simple "one"s are not what they seem. The temptation is to view them as examples of the famous "one-stroke" Zen approach to calligraphy. But in fact, Tawara spent much time embellishing his initial brushwork with a rich vocabulary of dribbles, streaks and blobs, so that every ichi takes on the features of a landscape all its own.

Occupying the four walls of just one large gallery at the museum, and adding up to less than a hundred pieces, the Tawara exhibition is compact but hardly lightweight. By the time you have made the circuit and perused all the works on display -- every one of which will call out to you for prolonged scrutiny -- you will find that a sizable amount of time has flown by. Or rather, has stopped altogether.

|

|

| |

Nerima Art Museum |

| |

6 December 2014 - 8 February 2015 |

| |

1-36-16 Nukui, Nerima-ku, Tokyo

Phone: 03-3577-1821

Hours: 10 a.m. - 6 p.m. (last admission at 5:30 p.m.)

Closed Monday (or Tuesday when Monday is a national holiday)

Access: 3-minute walk from Nakamurabashi Station on the Seibu Ikebukuro Line |

|

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for 28 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|