|

Wall of the Sea (2007), three-channel video with sound; installation view at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, 2011. © Takashi Ishida; photo by Haruyuki Shirai |

Multimedia art has become so commonplace that artists who combine sight with sound, and sometimes touch, are a dime a dozen these days. Nowhere is this truer than in Japan, where cutting-edge technology is the driving force in so many realms of endeavor, not least the creative arts.

As they say, though, genius will out, and it is always a thrill to come across someone with a conception so original and compelling that it grabs technology and runs with it, shaping it to its own ends, rather than merely toying with the latest gadgetry. Takashi Ishida is one such force to be reckoned with. His vision is unique, and its evolution over the past two decades suggests that he is on a perennially restless quest for new means of giving it form.

|

|

|

|

|

|

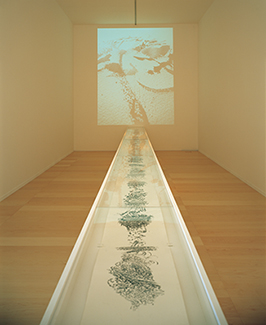

Unasaka (Slope of the Sea) (2007), silent video with scroll drawing in India ink on paper; installation view at the Yokosuka Museum of Art, 2007. © Takashi Ishida |

|

Emaki (Wave) (2010), video still of scroll

drawing in ink on paper. © Takashi Ishida |

Ishida's work is all about medium and process. It is so abstract, and devoid of sociocultural references, that one can search in vain for any signs of a "message." From interviews it is clear that the world at large does affect and motivate him, but his creations are purely about light, sound, and movement. They defy interpretation. The effect on the viewer is mystical, an appeal to the intuition, beyond analytical thought.

Until the end of May the Yokohama Museum of Art is offering a massive retrospective of Ishida's works, each of which could easily occupy an entire gallery. Because they unfold over time -- most involve films that last anywhere from a few seconds to 20 minutes -- it could take an entire day to fully absorb all of these installations. If you have a few hours to spare, though, this show is well worth the investment. Just as fascinating as the individual works is the progression one sees in Ishida's development as he revisits certain motifs and adds new ones. Growing up in Tokyo in a musical household (his father was a music critic and his mother a singer), he began looking for ways to express sound through art while still a teenager. This gave birth to one of his prevailing motifs: curving lines, rendered calligraphy-like in sumi ink, which extend, split, and multiply like tendrils of jungle foliage or cascades of rushing water.

|

|

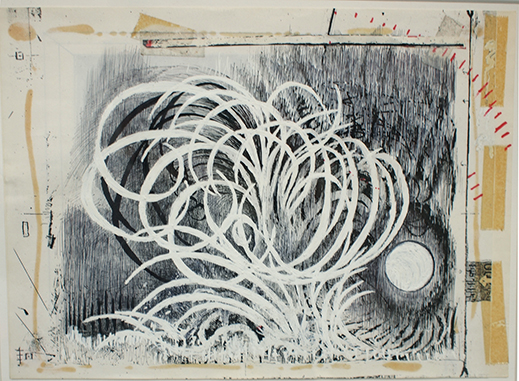

Original drawing from Die Kunst Der Fuge (The Art of Fugue) (2001), pen, ink, and whiteout on paper. © Takashi Ishida |

Early on Ishida sought ways to generate these fluid, organic forms in real time, leading him to develop a stop-motion "drawing animation" technique in which he draws a pattern, shoots it with a fixed-point camera, then draws some more and shoots again. He began making animated films of growing, flowing works like Unasaka (Slope of the Sea), which he painted bit by bit on a long scroll of paper. The video Ishida shot of this process carries the viewer along like the crest of a wave racing across sand.

In time Ishida introduced another motif that seems diametrically opposed to his spiraling curves: a square frame. In an interview he explains: "These swirling lines can stretch out forever and lose all shape, and the new task I set myself was to somehow contain them in a rectangular framework." He also began creating works integrated with music -- by Bach, Berg, and Shostakovich, as well as his composer brother. The 19-minute The Art of Fugue, which attempts to visually reproduce the intertwining, recurring leitmotifs of Bach's masterpiece, is a glorious summing-up of his experiments with these various elements. A tour de force of pulsing, shape-shifting squares and swirls, the film packs a psychedelic punch reminiscent of the trip into hyperspace that climaxed Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The rectangle is still a prominent motif in Ishida's work today, but it has morphed into many variants: windows, doors, tables, entire rooms. His compositions themselves have expanded in scale and acquired a certain poignancy. Without explicitly addressing the human condition, images of habitation -- furniture, houses -- undergo processes of disintegration and destruction, hinting at darker, more ambivalent emotions than his earlier, more abstract work. Burning Chair depicts just that, as flames appear to consume a simple stool at the center of an eerily static tableau. In Where Light Falls, a large canvas suspended at an oblique angle in an otherwise bare concrete room is painted over many times and ultimately slashed and shredded, while light and shadows play across the walls as time passes from day to night and back again.

|

|

Burning Chair (2013), video with sound. © Takashi Ishida |

One of Ishida's loveliest compositions, Reflections, was created over the course of a month in the brick-walled room of an old building in Portsmouth, England. The artist painted a section of the wall with a series of patterns that ebb and flow over time, but what makes the piece sublime is the shifting light that comes through the single window. The soundtrack consists of ambient sounds the artist recorded while walking to the building each day.

One might say that the underlying theme of Ishida's art is time itself. He is fascinated by transience -- the eternal flux of phenomena, how everything emerges and dissolves back into nothingness. The most graphic examples of this concern are films shot on beaches or streets, where he uses a mist sprayer to draw in the sand or on the pavement in swirling patterns that wash away or evaporate as quickly as he creates them. It's easy to see this as an ongoing contemplation of the evanescence of life, but Ishida adds no such conceptual baggage, letting the work speak for itself.

|

Where Light Falls (2015), video with sound; painting in acrylic, watercolor, and chalk on canvas. © Takashi Ishida |

Above all, these compositions are quite simply beautiful, hypnotic, and one-of-a-kind. If there is a problem with the current exhibition, it is that every one of Ishida's installations merits a solid hour's worth of concentrated attention. I would have preferred to experience them in small doses -- in the galleries where they initially appeared, one or two at a time, perhaps. Viewing such large-scale, time-demanding works in rapid succession eventually induces a bit of numbness in the beholder. But Ishida's oeuvre, at least as represented in this show, doesn't have a weak link in it. If you can, allow yourself a day to see it all, and take a couple of breaks -- for a walk, lunch or coffee -- in order to approach each work with a fresh mind.

The still photos shown here cannot do justice to the actual installations, of which motion is such an integral element. Due to copyright restrictions, there are no full-length videos of Ishida's work in the public domain. However, this video digest of very short (under five seconds each) excerpts from several of the works at the Yokohama show was posted online with his permission.

You can also see an interview with Ishida here on the museum website. Though the dialogue is in Japanese, it offers some generous glimpses of his works.

Finally, the artist's website has pages in English and shows numerous still images from his portfolio. The museum also deserves credit for providing full English translations of the very thorough explanatory texts that accompany the exhibition.

The artist at work on Wall of the Sea at the Yokohama Museum of Art, 2006. © Takashi Ishida

All images are courtesy of the Yokohama Museum of Art. |

|

|

| |

3-4-1 Minatomirai, Nishi-ku, Yokohama

Phone: 045-221-0300

Hours: 10 a.m. - 6 p.m. (admission until 5:30 p.m.)

Closed Thursdays

Access: 3 minutes' walk from Minatomirai Station on the Minatomirai Line; 10 minutes' walk from Sakuragicho Station on the JR Negishi Line |

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for 30 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|