|

Entrance to the Clark Center Gallery. Photo courtesy of the Clark Center |

It sat in the middle of the flattest, hottest part of California's Central Valley, surrounded by endless rows of almond trees. One is tempted to say "in the middle of nowhere" but that would be an insult to the good citizens of Hanford, the nearest town. This is, after all, where one native son, Willard Clark, single-handedly amassed one of the largest privately owned collections of Japanese art anywhere outside Japan -- and built a museum to house it. An astonishing labor of love and good taste, the Clark Center for Japanese Art & Culture was open to the public for 20 years, from 1995 until this past June 30 when it closed for good.

Happily for Japanese-art aficionados in the U.S., the museum's holdings are safely in the hands of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Along with the entire collection, which has an estimated value of $25 million, the MIA acquired the Center's curator, Andreas Marks, who now oversees the institute's Japanese and Korean art. Although it's most of the way across the country, the MIA was willing to look after the Clark Collection and keep it intact when museums in California failed to show interest. Fortunately for Central Valley residents, the Clark Center's equally impressive bonsai garden has found a home closer by, at the Shinzen Friendship Garden in nearby Fresno.

|

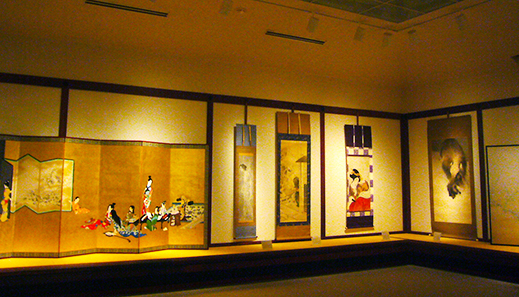

Interior of the Clark Center Gallery. Photo courtesy of the Clark Center |

Though I was living in the Bay Area, only three hours away by interstate, when the Clark Center opened, I had only vaguely heard about the place and wasn't prompted to visit it until about two years ago, when Bill Clark wrote to say that he read and enjoyed Artscape Japan. I made a mental note to check out his museum on one of my trips home, then promptly forgot about it until I learned that the Center would be closing this summer. Luckily I was planning to visit the Bay Area in June, so with a slight itinerary adjustment my wife and I were able to drive downstate to Hanford three days before the Center's closure.

Six miles south of Hanford, a modest sign indicated where to turn off a country road onto a gravel drive with almond orchards on both sides. After about a half-mile, the driveway abruptly ended at a parking lot next to what appeared, incongruously, to be a Japanese temple wall of tan stucco framed by sturdy wooden crossbars. A rustic shake-roofed gate led inside the compound, where we found a large one-story stucco building, also in Japanese style, surrounded by grounds landscaped with pines, rocks, and stone lanterns. Coming upon this scene on a hot summer afternoon in the midst of a Central Valley farmscape was, in a word, disorienting.

|

Part of the karesansui-style rock garden surrounding the Clark Center Gallery. Photo by Alan Gleason |

Entering the exhibit hall, we passed through a foyer with a selection of works from varying eras into the main gallery. This was a spacious, high-ceilinged room ringed with a stunning variety of works. The exhibition was nothing if not eclectic. As the 1,700-piece collection had already been moved to Minnesota, this, the Center's valedictory show, represented the temporary return of a few select highlights -- only a couple of dozen in all. If that gave the show a somewhat scattershot aspect, it also whetted one's appetite for more. We found ourselves wishing we could fly to Minneapolis right then and there.

Clark has described himself as an "unrestrained, undisciplined, crazy collector." So it is no surprise that his acquisitions run the gamut of genres -- scrolls, screens, sculptures, ceramics, kimono -- from the eighth century to the present. But thanks to his own judicious eye, as well of those of the experts he eagerly sought out, there is no dross in the gold here. Of particular note are the collection's Kamakura-period Buddhist sculptures, its Edo-period paintings, and some fine folding screens, one pair of which, a 12-panel tour-de-force by the 19th-century artist Shibata Zeshin entitled The Four Elegant Pastimes, formed the centerpiece of the final Hanford exhibition.

|

|

|

|

| Scrolls and screens on display in the Clark Center Gallery's final exhibition, Elegant Pastimes: Masterpieces of Japanese Art from the Clark Collections at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Photos by Kaoru Moriyama |

Judging from the overall selection, it seems that the collector's real soft spot is for Edo-era and later scroll paintings, particularly landscapes in sumi ink. There were some gems on display by the likes of Kano Sansetsu (early 17th century), Ito Jakuchu (late 18th century), Yokoi Kinoku, Yamamoto Baiitsu, and Kikuchi Yosai (early, mid-, and late 19th century respectively), and Fukuda Kodojin (early 20th century). Another standout was a pale-blue porcelain urn by Sueharu Fukami, a contemporary ceramist whose works are a favorite of Clark; he has purchased about 80 of them.

How did all of these works wind up in central California? Even the collector himself has a hard time explaining this. In an interview published on the Center website here, Clark recalls being captivated by a photo of a Japanese garden in his sixth-grade geography book. Much later, while serving in the U.S. Navy, his squadron was frequently deployed to Japan, where, he says, "the beauty of everything astounded me." Later still, in the mid-1950s, he and his wife traveled in Japan for several weeks and bought their first Japanese art. From then on the fix was in. Returning to live and work on the family dairy farm in Hanford, Clark eventually designed and built a Japanese-inspired house and pond. A fortuitous meeting with Kodo Matsubara, a Japanese landscape architect who was designing gardens in California, led to a lifelong collaboration during which Matsubara lent his skills and tastes to the construction and expansion of the Clark Center.

|

|

Landscaping around the Clark Center Gallery building. Photo by Alan Gleason |

By the late 1970s Clark was forming connections with dealers in Japanese art in New York and elsewhere, and making increasingly frequent purchases of paintings and sculpture of various eras. Bill and his wife Libby launched the nonprofit Clark Foundation for the Study of Art in 1995 and moved their collection into a newly completed gallery. Eventually renamed the Clark Center for Japanese Art & Culture, the facilities that just closed are the culmination of a gradual expansion of what began as an extra wing on the family home. One of only two U.S. museums devoted exclusively to Japanese art, at its peak the Center was holding four exhibitions and drawing 5,000 visitors annually; today it sits empty among the almond groves. The Clarks have not commented on what will happen to the buildings and grounds, which they still own.

Sadly, Bill Clark was not well enough to be at the Center during its last days of operation. One wishes that his accomplishments were better known in the homeland of the masterpieces he so admired. Still, he is not without recognition in Japan. Clark is one of very few Americans to have received two Orders of the Rising Sun from the Japanese government -- one for innovations in cattle farming that improved the Japanese dairy industry, and one for his promotion of the study of Japanese art and culture. Let us hope his legacy can be preserved in the Central Valley as well.

View through the gate of the Clark Center to the almond orchards stretching beyond. Photo by Kaoru Moriyama

All images by permission of the Clark Center for Japanese Art & Culture.

|

|

|

| |

Hanford, California

(The Clark Center closed permanently on June 30, 2015.) |

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for 30 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|