|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Adhering to the Concept: Yoko Ono at MOT

Alan Gleason |

|

|

Yoko Ono, Vertical Memory (1997), 21 framed iris prints with texts; installation view, BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, England (2008); photo by Colin Davison, private collection © Yoko Ono 2015. |

Yoko Ono needs no introduction; she is a global celebrity who has attracted praise and opprobrium in equal parts. The accolades tend to cite her commitment to progressive political causes and her success as a woman negotiating the male-dominated milieus of contemporary art and, later, of pop music. The negativity usually revolves around her marriage to John Lennon, whose romance with Ono was blamed early on for the breakup of the Beatles and whose coattails she has often been accused of riding on, both in life and death.

All of the hype, good and bad, obscures the fact that long before she met Lennon (famously, at her solo show in a London gallery in 1966), Ono had already established herself as a pioneering conceptual artist. Happily, the retrospective currently up at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo reintroduces her early work, reminding us that her very public persona -- both as artist and as musician -- is firmly grounded in her work of the fifties and sixties.

|

|

|

|

Yoko Ono, From My Window: Salem 1692 (2002), pigment on stretched canvas, private collection © Yoko Ono 2015. |

Ono has never professed to be a visual artist in the conventional sense. From the outset her media of choice have been her own body and the written word. Above all, she operates in the realm of ideas, particularly those that cannot be given tangible form in the "real" world. Growing up in an elite Tokyo family before and during World War II (she was born in 1933), she attended a progressive kindergarten where a free-thinking teacher introduced her to the notion that everyday sounds could be construed as music. After the war she entered the posh Gakushuin University but soon dropped out to move to New York City, where her parents were then living.

|

|

|

|

|

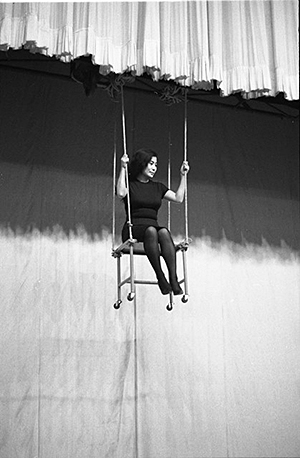

Yoko Ono, Chair Piece, performed by the artist, October 12, 1962, during Event of John Cage and David Tudor, Kyoto Kaikan Hall, Kyoto, Japan; photo by Yasuhiro Yoshioka, courtesy of Lenono Photo Archive © Yoko Ono 2015. |

Ono's timing could not have been better, because postwar artists in the city were just beginning to explode the boundaries of what constituted "art." Groups like Fluxus picked up where Dada had left off. Marcel Duchamp was still alive, and composers like John Cage and La Monte Young were applying such concepts as found objects and indeterminacy to music. To Ono, their experiments most likely seemed a natural extension of her own childhood influences. She quickly became a fixture on the New York art scene with works that, in hindsight, were among the earliest to fit later definitions of "conceptual art." One of the first was the self-explanatory Painting to Be Stepped On, followed by the legendary Cut Piece, a performance in which Ono knelt on a stage and invited audience members to cut off pieces of her clothing.

|

|

|

|

|

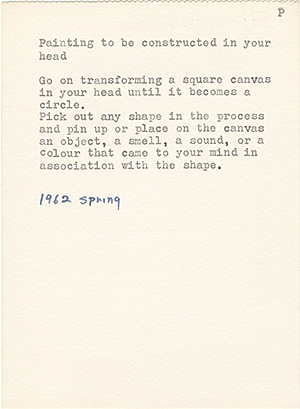

Yoko Ono, Painting to be constructed in your head (1962 spring), typewriter and ink on white Japanese "Apollo" postcard, private collection © Yoko Ono 2015.

|

Then, in 1964, she published Grapefruit, a set of instructions to be carried out entirely in the imagination. The ideas range from the whimsical -- "Take a tape of the voices of fish on the night of a full moon" -- to the morbid -- "Hide until everybody goes home. Hide until everybody forgets about you. Hide until everybody dies." Some could actually be implemented, as Ono did in subsequent performance pieces, but most lay purely in the realm of thought experiments. Many of the instructions were cinematic or musical, presaging her later films (Fly, Bottoms) and musical exploits (one of the first that brought her to my attention as a teenage Beatle fan was "Don't Worry Kyoko, Mummy's Only Looking for Her Hand in the Snow," her brilliantly titled tour de force of wailing and moaning on Ono and Lennon's album Live Peace in Toronto 1969).

Unfortunately for Ono's reputation as a serious artist, I think that people (including me) overlooked the sheer originality and chutzpah of Grapefruit only because aphorisms like "Count the clouds. Name them." got conflated with the fluffy, easily parodied feel-good adages of the New Age. But Ono was no flower child, as the book's tough, even punkish allusions to sex, death, and existential absurdity will attest.

|

|

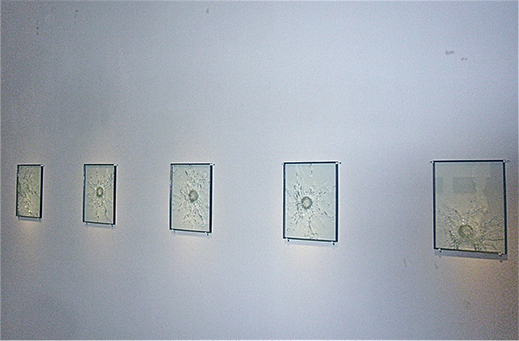

Installation view of A Hole (2009), sheets of shot glass, private collection © Yoko Ono 2015; photo by Alan Gleason. |

The MOT show's emphasis on "early Ono" is fine with me; it's an edifying pleasure to see films like Cut Piece and Fly in their entirety, and you can purchase a reprint of the "classic" edition of Grapefruit in the museum shop. The more recent pieces on display seem to dwell inordinately, if inevitably, on the tragedy of her husband's murder in 1980. Sometimes this fixation yields powerful work, sometimes not so much. An example of the former is the installation A Hole, which includes a series of small, identically sized glass panes, each shot through with a single bullet. The violent subtext speaks for itself, but what makes the work compelling is the snowflake-like beauty and uniqueness of each pattern of shattered glass.

|

|

|

|

|

Yoko Ono, A Hole (2009), large sheet of shot glass with the engraved text: GO TO THE OTHER SIDE OF THE GLASS AND SEE THROUGH THE HOLE; metal support. Detail. First exhibited at Gallery 360 Degrees, Tokyo (2009); private collection © Yoko Ono 2015. |

More problematic is the titular From My Window: Plaza, a row of color prints of Ono and Lennon sitting and smiling at each other at their kitchen table; behind them a window looks out over Central Park. Each iteration of the image is progressively darker, till the last one fades completely to black. Though no doubt a sincere evocation of Ono's personal feelings about loss and memory, it tugs so overtly at the viewer's heartstrings (particularly if you're a Lennon fan) that it is hard to view dispassionately as art. Another From My Window series, overlaying the same window view with a childhood photo of Ono and a painting of the Salem Witch Trials, similarly leaves one with mixed emotions.

|

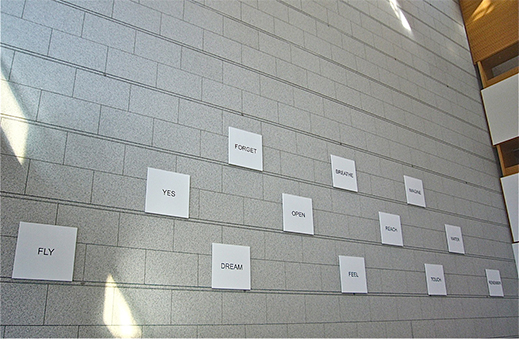

| Yoko Ono, Word Pieces (2015), black pigment on 12 white canvases, private collection © Yoko Ono 2015; photo by Alan Gleason. |

An atrium-high wall covered with placards bearing one-word slogans -- FLY, YES, FORGET, DREAM, OPEN, BREATHE, FEEL, REACH, and so on -- typifies one of the recurring motifs in Ono's oeuvre, but otherwise doesn't have much impact. Overall, this show, while a solid and respectful presentation of the artist's long and varied career, is a rather staid affair that made me miss the playful, real-time elements of some past Ono exhibitions. A few years ago, I attended another Ono show in Tokyo that had a telephone sitting in the corner of the gallery. The idea was that Ono would dial the number at odd intervals and speak to whoever picked up the receiver. Unaware of this, a friend who happened to be standing near the phone when it rang picked up, and when the other party said "Hello, this is Yoko Ono," refused to believe her and demanded to know who it really was. Ono remonstrated but finally hung up in a huff, or so my friend claims. Perhaps the current exhibition could have benefited from a bit of this sort of randomness.

|

|

Yoko Ono, Cloud Piece (1963/2005), part of the permanent installation Sky TV for Hokkaido, Millennium Forest, Hokkaido, Japan © Yoko Ono 2015. The instructions for the work read as follows:

CLOUD PIECE

Imagine the clouds dripping.

Dig a hole in your garden to

put them in.

1963 spring |

| All images are courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo except where otherwise indicated. |

|

|

| |

4-1-1 Miyoshi, Koto-ku, Tokyo

Phone: 03-5245-4111

Hours: 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. (last entry 30 minutes before closing); closed Mondays (except when Monday is a national holiday; museum closes the following Tuesday), and 15 February - 4 March 2016 for exhibition installation

Access: From Kiyosumi-Shirakawa Station, 9 minutes' walk from exit B2 on the Tokyo Metro Hanzomon Line or 13 minutes' walk from exit A3 on the Toei Oedo Line |

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for 30 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|