|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Shades of Gray: The Photographic Alchemy of Kenro Izu

Alan Gleason |

|

|

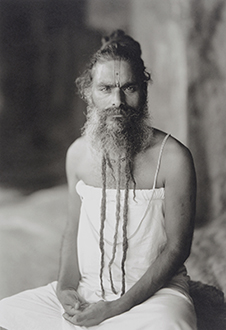

India, Where Prayer Echoes, Rameswaram #665, India 2012; platinum-palladium print. © Kenro Izu |

A massive, starkly modern concrete structure, the Kiyosato Museum of Photographic Arts (K*MoPA) looms incongruously above the forests of the Yatsugatake Highlands at the end of a narrow winding road, far from the nearest highway. Once a visitor enters, though, the building is a revelation. A vaulted, cathedral-like atrium lets in ample sunlight, and a terrace in back is shaded by trees that encroach from the surrounding woods, seemingly on the verge of overrunning the hard gray surfaces of the building. The effect is like stumbling across a Mayan temple ruin designed by Bauhaus.

Despite its isolated setting, the museum is reasonably accessible. About two hours west of Tokyo by car or rail, it's not that far from an expressway exit, but most visitors will prefer to ride the bucolic Koumi Line as it chugs across a scenic plateau lush with mountain vistas, then disembark at Kiyosato Station and grab a cab. Still, it's easy to see why some might find the trek daunting. On a recent summer Friday the cavernous building was nearly deserted, and much of it is currently unused: the exhibition galleries occupy only part of the first floor, and a lovely outdoor concert space fills with music only once or twice a year.

|

|

|

|

The terrace and galleria of K*MoPA. |

More's the pity, because the museum's commitment to photographic art is unassailable. Since it opened in 1995, K*MoPA has been guided by director Eikoh Hosoe, a living icon of postwar Japanese photography, now 83 and still going strong. One Hosoe brainchild is the museum's Young Portfolios program (previously featured here in Artscape), through which it solicits work by photographers age 35 or younger. The works selected under the program make up one of three major exhibitions the museum holds each year.

In his director's message on the museum website, Hosoe cites three exhibiting principles or policies espoused by K*MoPA. First is the rather all-encompassing "Affirmation of Life"; another is "Photographs by the Next Generation," as represented by the Young Portfolios program. The third is intriguing because it is technically so specific: a commitment to "Eternal Platinum Prints." For those who don't know (I sure didn't), platinum produces monochrome images that boast an unparalleled richness of tone, particularly grays, and the prints are extremely durable. The process dates back to the earliest days of photography, but fell out of favor when platinum prices soared during World War I. Thereafter the gelatin silver process became the default option for black and white photography. Lately, though, platinum and platinum-palladium prints have enjoyed a revival among contemporary photographers who like to work in monochrome.

|

|

|

|

India, Where Prayer Echoes, Ellora #460, India 2010; platinum-palladium print. © Kenro Izu |

|

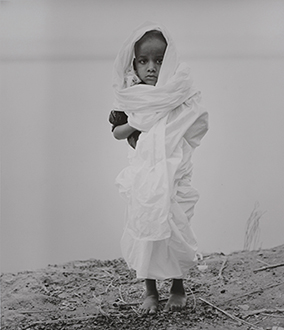

Eternal Light 35 #5, Narainpur, February 2013; gelatin silver print. "Chithdu Ria, a five-year-old boy with a shaved head and dressed in white, is a chief mourner of his mother at Narainpur cremation ground at dusk. Because his father passed away last year, he now is the only remaining member of the family." © Kenro Izu |

One of the platinum print's foremost champions today is Kenro Izu. Born in Osaka in 1949, he traveled to the U.S. in 1972 and ended up living there. A wanderer at heart, he has devoted much of his career to photographing sacred places around the world. Eternal Light, Izu's current solo show at K*MoPA, is a revelatory marriage of content and technique, with exquisite examples of his work in both platinum-palladium and gelatin silver.

Eternal Light 441 #8, Narainpur, February 2015; gelatin silver print. "Sunset over a cremation at Narainpur." © Kenro Izu |

|

Eternal Light 171 #10, Saidpur, January 2014; gelatin silver print. "As the flames gain intensity, the setting sun over the fire appears as if a mirage."

© Kenro Izu |

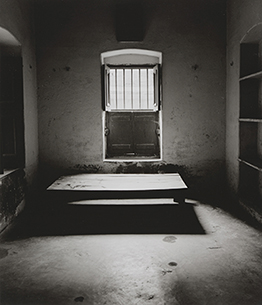

Izu has been visiting India for several decades, lugging his camera of choice -- a massive 14" x 20" Deardorff -- to holy spots throughout the subcontinent. Between 2006 and 2013 he produced an epic platinum-palladium series, India, Where Prayer Echoes. For the past three years he has focused on the lives of people in holy cities along the Ganges and Yamuna rivers. The resulting series, Eternal Light, is a moving example of technical mastery placed in the service of profound and often unsettling subject matter. Izu films cremations on the ghats at Varanasi; families tending to dying loved ones in a "House of Liberation" that provides free lodging for that purpose; widows living a cloistered life in Vrindavan, a center of Krishna worship, after being cast out of their homes when their husbands died; and young children, overwhelmingly girls, in a Varanasi orphanage. These are images of death and deprivation, yet they brim with life. Eyes, skin, water, flames -- all emit a sublime luminosity in Izu's hands.

|

|

|

|

Eternal Light 23 #12, Varanasi, February 2013; gelatin silver print. At the House of Liberation: "They have been married for 70 years. When the 100-year-old man struggled unconsciously, the wife came up and held his hand and whispered to him. The man regained calmness." © Kenro Izu |

|

Eternal Light 14 #4, Varanasi, February 2013; gelatin silver print. "The morning after the departure of an occupant. The room has been washed and cleaned already." © Kenro Izu |

The current show includes works from India, Where Prayer Echoes as well as Eternal Light. The former, while stunningly beautiful, have a cooler documentary feel to them, whereas the latter -- perhaps because they were shot in closer proximity to their subjects -- seem warmer and more intimate. The physical constraints of shooting indoors in such places as the House of Liberation prevented Izu from using his big Deardorff; consequently he shot Eternal Light with a medium-format camera and printed on gelatin silver instead of his trademark platinum. I certainly can't tell the difference. All of Izu's images are so rich that one forgets they are monochrome; if anything their subtle shades of gray are more evocative than color photography could ever be.

After some time immersed in Izu's intense scrutiny of lives lived in the face of death, the museum's terrace provides a welcome respite. Here you can submit to the gentle caress of breezes blowing down through the Kiyosato woods from Mt. Yatsugatake. No moment could be more life-affirming.

|

|

Eternal Light 102 #7, Vrindavan, February 2014; gelatin silver print. "Shanti Bai, who has lived for 48 years in Vrindavan, said, 'Do I have an objective in life? I have left behind all objectives in life and came to the refuge of Krishna and Radha. This atman (soul) will depart from this body and merge in Paramatman (the almighty). I fast often on religious days like today, the Ekadashi (eleventh day of the Hindu month). And I enjoy listening to the Bhagwat (a story of Krishna and his teachings), which gives me joy.' Shanti also said, 'I am sad forever and happy forever.'" © Kenro Izu

All photographic works and quotations by Kenro Izu; all images courtesy of the Kiyosato Museum of Photographic Arts.

|

|

|

| |

3545-1222 Kiyosato, Takane-cho, Hokuto-shi, Yamanashi Prefecture

Phone: 0551-48-5599

Hours: 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. April-November, to 5 p.m. in December; last entry 30 minutes before closing

Closed Tuesdays and from year's end through late March

Access: 10 minutes by taxi from Kiyosato Station on the JR Koumi Line, about 2 1/2 hours west of Tokyo (transfer from the JR Chuo Line at Kobuchizawa); by car, 20 minutes from the Sutama Exit on the Chuo Expressway |

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for 30 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|