|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spirits in the Hills: Seeing the Unseen at Gallery Ohrin

Alan Gleason |

|

|

The shimenawa at Hitachinokuni Izumo-taisha, said to be even larger than the sacred rope at the original Izumo-taisha shrine in Shimane. |

Shinto shrines and contemporary art are two terms that rarely occupy the same sentence. The institutions associated with Japan's indigenous religion tend to hew to tradition and leave dabblings in modernity to Zen Buddhist temples and the like. So it is a pleasant surprise to discover one shrine that bucks the stereotype and has actively opened its doors to contemporary art, even building a gallery for that purpose. The location is also unexpected: Hitachinokuni Izumo-taisha sits on a hilltop far from the nearest city and a good 100 kilometers northeast of Tokyo.

Located in the lush rolling countryside outside Kasama, a town in Ibaraki Prefecture known for its pottery kilns, the shrine boasts an ancient pedigree but is actually quite new. It was initially affiliated with the grand shrine at Izumo in Shimane Prefecture, far to the west, which many believe to be Japan's oldest Shinto sanctuary. Izumo-taisha founded branch shrines throughout Japan, and the one in Kasama is part of that tradition -- yet it only dates back to 1992, when it was established here by the present chief priest, Tadanobu Takahashi. A man with a vision, Takahashi built an impressive edifice that rivals the original in Shimane, with a mammoth shimenawa rope guarding the sanctuary and what is claimed to be the largest stone torii gate in the country. Now independent from the parent shrine, Hitachinokuni Izumo-taisha takes its name from Hitachi, the old provincial name for Ibaraki.

|

|

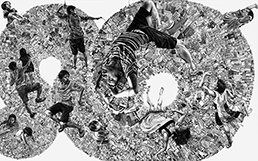

Installation view of Seeing the Unseen at Gallery Ohrin. At center is a sculpture by Ayano Nanakarage, rainbow edge I (2015), camphor wood, 114 x 70 x 40 cm. |

An artist himself, Takahashi makes glass works in a studio on the shrine precincts. He also has close ties to Tokyo's contemporary art milieu and fulfilled another of his dreams when he opened Gallery Ohrin this past February in a building that formerly served as the shrine's gift shop. A starkly functional space of the white-cube variety, the gallery would fit right in if transplanted to the capital -- but it also offers a fine view of the northern Kanto Plain, with Mt. Tsukuba in the distance. Collaborating with Mizuma Art Gallery, a major presence on the Tokyo scene, Ohrin has already embarked on a solid schedule of exhibitions by artists that, in Takahashi's words, "are filled with the Japanese spirit."

The current show, Seeing the Unseen (till 27 November), introduces eight women artists who are only beginning to earn some recognition. While no specific rationale for the all-female roster is given, in his preface to the catalogue Mizuma Gallery director Sueo Mizuma, who selected the artists, alludes to the prominence of goddesses in the Shinto pantheon, noting that its mythology is unique in placing a female deity, Amaterasu, at the top of the hierarchy. In any event, this is a strong lineup of works that are indeed imbued with a sense of the spiritual, of a reality that remains invisible to us yet permeates and influences our daily lives.

Each artist is represented by only one or two works, but most of these are large paintings. Even so the exhibition does not feel cramped, and the relatively small selection encourages the viewer to linger over each piece. That attention is not wasted, as every work is a product of accomplished technique and painstaking devotion to compositional detail. There are no creative shortcuts here, and only the slightest whiff in a couple of pieces of the anime/idol/kawaii tropes that dominate so much output by young artists in Japan these days.

|

|

Sayaka Toda, Garden of Ruins (2016), acrylic on canvas, 194 x 642 cm. |

The most eye-catching work here, Sayaka Toda's Garden of Ruins, is a two-by-six meter mural that fills an entire wall. Toda, who at 25 is the youngest of the show's participants, already displays a masterful command of color and composition, as well as an unsettling imagination. Dark reds predominate on a canvas filled with floating nude female figures whose heads and upper torsos are replaced (or consumed?) by gorgeous yet malevolent sea anemone-like growths spewing some sort of liquid. The work may defy interpretation, but its impact, on a purely visceral level, is mind-bending.

|

Momoko Fujita, Ame tsuchi o musubu (2009), Japanese paper, Japanese pigments, leaves, shell, sumi, acrylic, mixed media on panel, 230 x 400 cm. Photo by Norihiro Ueno. |

Nearly as monumental as Toda's submission, and much darker in hue yet ultimately less threatening, is Momoko Fujita's Ame tsuchi o musubu (which might be roughly translated "Joining Rain and Soil"), a semi-abstract painting that combines acrylic with traditional Nihonga pigments and other materials. What at first appears to be a gnarled, tree-like organism dripping strands of hair proves on closer inspection to house sacs of fetuses. Despite the dour tones of the piece, it feels life-affirming in a primordial, sprung-from-the-mud sort of way. Two more large paintings by Hitomi Noda, Waterfall and Losing Sight of Illuminating, conjure up a similarly eerie elixir of animistic forces with like materials, employing both acrylic and mineral pigments in the service of surreal landscapes in which female figures clothed only in animal hides carry lanterns through a dark forest, or crawl on all fours toward a cascade made of lace.

|

|

|

|

Hitomi Noda, Waterfall (2016), acrylic, pencil, shell powder and sumi on paper, 148.5 x 227 cm. |

|

Mikiko Kumazawa, Further Towards the Future (2010), pencil on gesso, mounted on panel, 227 x 363.6 cm. Photo by Norihiro Ueno. |

The only photorealistic works in the show, two large pencil-on-gesso drawings by Mikiko Kumazawa, seem cheerful and lively by contrast, as well as firmly rooted in the present, but the models -- urban youth in one piece and elderly retirees in another -- act out perplexity and anger respectively at the uncertainties of life with which society confronts them. With its bright pastel colors, teddy bears and gamboling sheep, Ayane Eguchi's Paradise or Hell is also deceptively "kawaii" at first glance, but the frolicking figures are drawn exorably down a spiral staircase into a black hole that hints at a sinister fate for all the sweetness and light on the surface.

|

Ayane Eguchi, Paradise or Hell (2015), oil on canvas, 162 x 194 cm. |

More assertive in her cooptation of pop imagery is Ryoko Kimura, whose ink paintings feature attractive young men modeled after real-life athletes and rock stars, surfing on the backs of crocodiles or soaring Icarus-like on huge wings. Turning the ukiyo-e genre of bijinga -- "pictures of beautiful women" -- on its head, her works toss a refreshing wink at the viewer, even as they skate perilously close to the world of manga-kitsch.

|

Ryoko Kimura, Born to be WILD! Crocodile (2009), ink on silk, 97 x 194 cm. |

Rounding out the exhibition are some impressive sculptures by Ayano Nanakarage and Saya Irie. Nanakarage presents two objects from her rainbow edge series, each carved from a single camphor tree. The rounded, shroudlike forms appear as abstractions at first, but protruding from below are leg-like appendages that resemble shrivelled vegetable stalks. At the opposite end of the figurative spectrum, Irie offers flawless miniature statues of two of Japan's deities of fortune, Benten and Daikoku -- made entirely out of eraser shavings. Inspired, Irie says, by the Izumo-taisha shrine, these are the only works here that directly reference religion. They are appropriate choices, particularly Benten, who is Japan's version (via Buddhism) of the Hindu goddess of the arts, Sarasvati.

This is a sturdy assemblage of works that without exception explore, in imaginative ways, the notion of worlds hidden behind the one we take for granted. A stroll through the shrine grounds, particularly the ecologically progressive back-to-nature cemetery in the woods behind the sanctuary, is sure to enhance the sensation that these hills are alive with spiritual forces beyond our reckoning.

|

|

Saya Irie, Benten Dust (2014), eraser shavings, 20 x 7.5 x 10 cm. Installation view from Tsushima Art Fantasia 2014; photo by Tadasu Yamamoto. |

All images courtesy of Gallery Ohrin and Mizuma Art Gallery. |

|

|

| |

Hitachinokuni Izumo-taisha

2081 Fukuhara, Kasama-shi, Ibaraki Prefecture

Phone: 0296-71-6700

Hours: 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m.; closed Wednesdays

Access: 7 minutes' walk from Fukuhara Station on the JR Mito Line, about 1 1/2 hours from Tokyo (transfer from JR Joban Line at Tomobe Station); 5 minutes by car from Kasama-Nishi exit on the Kita-Kanto Expressway |

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for 30 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|