|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

True Colors: Rediscovering the Vibrant Palette of Edo Art

Alan Gleason |

|

|

Aobana (Asiatic dayflower) petals, used for a blue dye that was popular for ukiyo-e in the 18th and early 19th centuries. |

|

Rokusho ("green-blue") pigment made from malachite; the finer the particles, the brighter the color. |

One of the attractions of ukiyo-e and Nihonga is their use of traditional Japanese pigments derived from natural substances. I have seen amazing displays of the Nihonga palette, which is said to employ some 10,000 pigments in all, most of them made with minerals like malachite, azurite, and cinnabar, as well as metal oxides, clays, shell, and coral. Though Nihonga is a relatively recent genre that dates to the Meiji era (1868-1912), its colors, I assumed, were a legacy of the ukiyo-e of a previous generation, but it turns out this is not quite true. Edo-era (1603-1867) painters and woodcut artists relied more on translucent dyes from plants like safflower, turmeric, and indigo. Moreover, the techniques for making those dyes were lost amid the onslaught of Westernization that came with Meiji.

Nor is the "natural" monicker entirely applicable, whether to Nihonga or ukiyo-e. Prussian blue, the first modern synthetic pigment, was imported into Japan in the 18th century, not long after its invention in Europe. Ukiyo-e masters like Hokusai and Hiroshige quickly took to it because it was much cheaper than, say, the ultramarine blue made from the semiprecious stone lapis lazuli. Thus even before the end of Edo, natural dyes were giving way to synthetics.

|

|

Showcase of ukiyo-e pigments at the Meguro Museum of Art. |

In my ignorance I had always thought that those late-Edo imported dyes were to blame for the vivid, sometimes garish reds and blues and purples of mid-19th-century ukiyo-e, and that the subdued works of 18th-century artists could be attributed to their use of more somber, more "natural" coloration -- but duh! The early prints we see in art museums today have, of course, faded with time. Now, with all kinds of hi-tech analytical tools at their disposal, researchers can give us an idea of what those early ukiyo-e really looked like when they were fresh off the woodblock.

Until 18 December, the Meguro Museum of Art, Tokyo is the place to see the fruits of one man's labor of love in this regard. As part of its revival of The Anatomy of Colors, a series of exhibitions that first ran between 1992 and 2004, the museum is showcasing the work of Inuki Tachihara (1951-2015), an autodidact who doggedly pursued his dream of reproducing ukiyo-e in their true colors and was rewarded with recognition of his efforts by Japan's art establishment as well as a prize from the Japan Society for Analytical Chemistry.

|

|

|

|

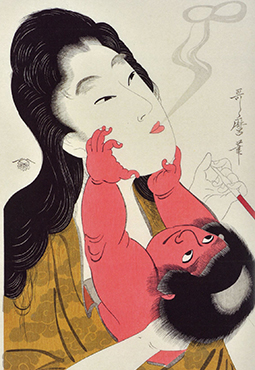

Kitagawa Utamaro, Yamamba and Kintaro: Smoke of Tobacco, ca. 1801-03; Hagi Uragami Museum, Yamaguchi Prefecture. |

|

Inuki Tachihara, Yamamba and Kintaro: Smoke of Tobacco (Kitagawa Utamaro), 1982; Inuki Art. |

Tachihara's first career was as a jazz saxophonist, but an encounter at age 25 with a picture of a beautiful woman by Utagawa Toyokuni (1769-1825) inspired him to learn the secrets of Edo printmaking instead. Studying the techniques and materials of ukiyo-e on his own, Tachihara mastered all three components of the process -- drawing, engraving, and printing -- each traditionally the task of a different artisan. By the end of his life he had produced 78 original ukiyo-e and 71 reproductions of Edo-era works in what experts confirmed to be their authentic hues.

The show displays several of Tachihara's reproductions alongside originals on loan from various museums. The contrast is striking, to say the least: in a preserved original print of Kitagawa Utamaro's Yamamba and Kintaro: Smoke of Tobacco, dated ca. 1801-03, the mythical child hero Kintaro is a rather muted pink; in Tachihara's hands the superbaby's flesh is restored to its intended ruddiness, as befits his fathering by a red dragon. Other examples are no less revelatory.

|

|

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, A Famous View in Edo: Surugadai, ca. 1832-33; Hagi Uragami Museum, Yamaguchi Prefecture. |

Tachihara was notably devoted to the work of Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798-1861), one of the last of the great ukiyo-e practitioners and a maverick known for his showy coloration and subversive content. Because Kuniyoshi's work is more recent, the distinction between the originals and Tachihara's restorations is relatively subtle -- testimony to both Kuniyoshi's rich palette and Tachihara's fidelity to it. More dramatic is a Tachihara reproduction of one of the first nishiki-e, or full-color ukiyo-e, a 1767 print by Suzuki Harunobu (ca. 1725-70), who had perfected the multicolor process only two years earlier.

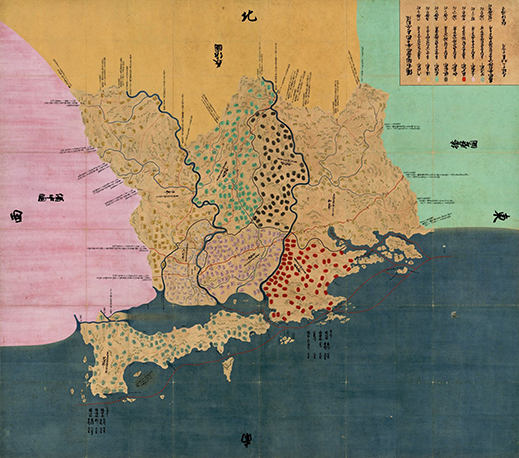

Another section of the exhibition introduces a different genre of Edo-era painting altogether, one that used the same variegated plant and mineral pigments as ukiyo-e, but for entirely different purposes. Kuniezu, literally "pictorial provincial maps," were prepared by order of the Tokugawa Shogunate in fiefdoms throughout Japan from the early 1600s on. Though their function was administrative, no expense was spared in producing these charts, no doubt as much a gesture of regional pride as of fealty to the Edo government. Artists of high repute, including some from the august Kano school, were hired to paint kuniezu using the same pigments as in their own work: mountains in malachite green, rivers and seas in azurite blue, roads and place labels in cochineal crimson, wisteria yellow, or cinnabar vermilion.

|

|

|

|

Kuniezu of the Bizen Region, 1596-1615, 329.0 x 280.7 cm; Okayama University Libraries, Ikeda Family Collection. |

|

Kuniezu of the Bicchu Region, 1624-44, 190.0 x 189.2 cm; Okayama University Libraries, Ikeda Family Collection. |

The maps on display are all from Bizen and Bicchu, neighboring provinces facing the Seto Inland Sea in what is now Okayama Prefecture. Fortunately for map buffs today, the region's ruling Ikeda clan and its successor, the Okayama prefectural government, did such a good job of storing a number of kuniezu that their colors seem to have hardly faded at all. The greatest artistic license was taken with the early, less cartographically precise efforts; the mountains on a Bizen map from the early 17th century are worthy of a Yamato-e landscape painting. By 1700, accuracy had taken precedence over visual appeal, and the results, as seen on another map from Bizen, were less pictorial and more utilitarian.

The kuniezu are a glorious sight to behold. Four of them, each laid flat and measuring two or three meters square, occupy their own showcases, which nearly fill the gallery. These are accompanied by a fifth made in 2010: a faithful reproduction of the 1700 Bizen map that took two months of meticulous labor by students in a lab at Tokyo University of the Arts. Based on analysis conducted at the University of Tokyo, they adhered to the materials and pigments of the original, much in the spirit of Tachihara's ukiyo-e exploits.

|

|

Kuniezu of the Bizen Region, 1700, 316.0 x 357.0 cm; Okayama University Libraries, Ikeda Family Collection. |

The walls of the kuniezu gallery are covered with photo enlargements that draw the eye to noteworthy details on the maps. Overall, the exhibition provides impressively thorough background information on its displays. Unfortunately for the non-Japanese visitor, however, none of the texts are in English.

Still, there is plenty of eye candy here that requires no explanation. A massive showcase outside the ukiyo-e room parades the entire gamut of Edo pigments in their natural and refined states. Greeting visitors on the ground floor are more cases of colorful stones, shells, and minerals. And, for the big picture, a bank of portfolio drawers awaits, chock full of fascinating mini-exhibits of the nuts and bolts of painting and printmaking both East and West -- not only pigments but papers and other materials, processes, tools, and on and on. Allow yourself a few hours to take it all in.

|

Installation view of the kuniezu exhibit at the Meguro Museum of Art. |

All images courtesy of the Meguro Museum of Art, Tokyo. |

|

|

| |

2-4-36 Meguro, Meguro-ku, Tokyo

Phone: 03-3714-1201

Hours: 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. (entry until 5:30 p.m.); closed Mondays (except on national holidays, when it is closed the next day), year-end and New Year holidays

Access: 10 minutes' walk from Meguro Station on the JR Yamanote Line, Tokyu Meguro Line, Metro Nanboku Line and Toei Mita Line |

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for 30 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|