|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Young Moderns: Taisho-Era Design at the Hibiya Library & Museum

Alan Gleason |

|

Installation view, Blooming of Japanese Modernism, Hibiya Library & Museum. |

The brief reign of Emperor Taisho, from 1912 to 1926, is remembered as a golden age when a truly modern hybrid of Japanese and Western culture first reached full flower. The preceding Meiji era (1868-1912) had been a tumultuous period of headlong modernization as well as fervent reaction against the onslaught of Western influences. By the end of it, artists were beginning to blend those influences with homegrown traditions in novel ways. Amid the peace and prosperity that followed World War I, cities were awash in new ideas and fashions as they enjoyed a distinctively Japanese version of the Roaring Twenties, complete with flappers known as moga, short for "modern girls."

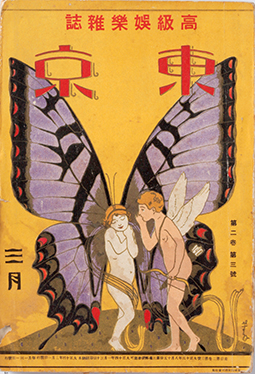

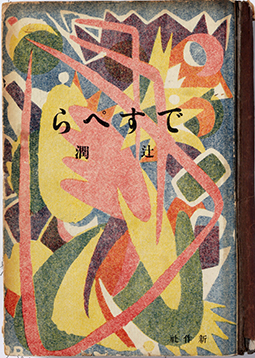

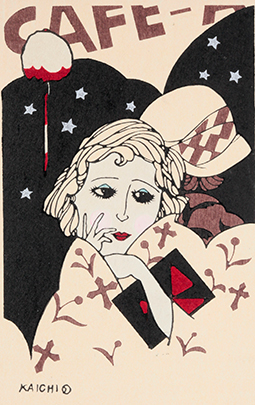

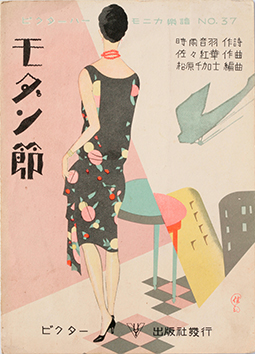

Sometimes referred to as the "Greater Taisho" era, the period from the turn of the century to the mid-1930s, a few years into the subsequent reign of Emperor Showa (1926-89), also saw a reappraisal of the culture and arts of the Shogunate-ruled Edo era (1603-1867) so disparaged by Meiji modernists. An inclination toward pre-Meiji nostalgia revived interest in ukiyo-e and other Edo cultural artifacts. Artists coming into their own in the teens and twenties of the 20th century often studied both Western and traditional Japanese art, and their experiments in mixing the two found ready outlets thanks to a burgeoning demand for designs on everything from book and magazine covers to advertisements, movie posters, cigarette packs and matchboxes.

Artist unknown, illustration in Shoten zuan senshu (Collected Retail Shop Designs), 1928. |

|

Harue Koga, cover of the art textbook Shin-bijutsu koza: Yoga-ka (New Art Course: Western-Style Painters), 1928. |

Until 7 August, the Hibiya Library & Museum in downtown Tokyo offers an eye-opening view of graphic design from this era in its exhibition Blooming of Japanese Modernism. Divided into "chapters" roughly by genre (commercial design, publications, children's and women's literature, Japonism, entertainment, fashion), the potpourri of items on display is helpfully organized so as to highlight specific artists.

Several names stand out. Hisui Sugiura (1876-1965) takes pride of place as a pioneer in his use of art deco and other modern design motifs in media ranging from covers for Mitsukoshi, the magazine of the flagship Ginza department store, to nearly all of the country's early cigarette packages. The latter is a fascinating genre in itself. Though tobacco had been smoked in pipes in Japan ever since it arrived with Portuguese traders in the 16th century, cigarettes only came into vogue during the Taisho. The tobacco industry, a state monopoly, began introducing one brand after another, and Sugiura was their go-to package designer. These are brilliant works in miniature, sometimes with downright bizarre graphics: His logo for Hibiki (Echo) cigarettes is a pattern of concentric radio signals radiating out over a row of smoke-belching factory chimneys.

|

|

|

|

Hisui Sugiura, cover of Tokyo magazine, March issue, Volume 2 No. 3, 1925. |

|

Artist unknown, cover of Desupera (Despair), 1924, a collection of essays by Jun Tsuji, self-proclaimed "first Dadaist in Japan." |

One of the most artistic book designers of the day was the painter Takeji Fujishima (1867-1943), who produced beautiful covers for literary works by such luminaries as the poet Akiko Yosano. Fujishima's designs amply substantiate the exhibition text's declaration that Taisho artists saw book and magazine design work as an opportunity to experiment more freely than they could with their own paintings. Fujishima, Sugiura, and a number of other Taisho artist-cum-designers shared a common pedigree, studying Western art with the seminal Western-style painter Seiki Kuroda (1866-1924) as well as Nihonga (Japanese-style painting) with the equally eminent Gyokusho Kawabata (1842-1913). Synthesizing these styles with aplomb, they transformed the traditional Japanese palette with bright pastel hues -- pinks, yellows, pale greens and blues -- that came to be known as "Taisho colors."

Taisho was also a golden age for periodicals. Everybody published magazines -- not only major retail establishments like the aforementioned Mitsukoshi, but also entertainment conglomerates, notably the Osaka-based Shochiku, which owned a stable of film and stage theaters and published the magazine Shochikuza News touting its productions. Among this show's most striking displays is the array of issues of that publication featuring covers by graphic designers like Shinkichi Yamada (1903-81), who started out as a movie poster artist for Shochiku but seamlessly melded elements of cubism, surrealism, and collage in avant-garde cover art that deserves to be framed.

Artist unknown, cover of Shochikuza News 10.4, 1931. |

|

Yumeji Takehisa, cover of Shojo no tomo (Girls' Friend) magazine, April issue, Volume 20, No. 4, 1927. |

The female figure had been a prominent motif in popular Japanese art at least since the Edo heyday of Bijinga, the "beautiful women" genre of ukiyo-e, but it gained special cachet during the Taisho, when women were finally achieving acceptance as full-fledged members of Japanese society -- especially as consumers. This period has sometimes been described as "the age of women and children" because for the first time, those segments of the population were deemed worthy marketing targets. Women's magazines and children's picture books proliferated, and artists like Sugiura and Yumeji Takehisa (1884-1934), famed for his depictions of lissome young women in both kimonos and Western garb, made names for themselves with their portrayals of female and juvenile subjects. If anything, the Hibiya show seems inordinately weighted toward images of women, particularly the ubiquitous moga.

|

|

|

|

Kaichi Kobayashi, Ni-go-gai no onna (Woman of Second Street), ca. 1925-26. |

|

Kazo Saito, cover of Modan-bushi (The Modern Song), Victor Harmonica Sheet Music No. 37, 1929. |

The exhibition provides some illuminating historical context. The Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 and the ensuing fires that leveled Tokyo triggered a wholesale shift of the nation's commercial and cultural activities to Osaka and Kyoto, and some historians argue that the freewheeling experimentalism of Kansai region designers, unencumbered by the establishment pressures of the capital, was a major factor in the flourishing of Taisho Modernism. Of course, in a matter of years Tokyo was back on top, its renaissance spurred by a government-led reconstruction of the city center with broad avenues and fireproof ferroconcrete buildings, much like the renovation of Paris not so much earlier.

One views the Taisho era's creative ferment with the foreboding of hindsight. Its association with the spread of mass media and commerce notwithstanding, Taisho Modernism was a style largely of and for the wealthy urban class. As we know all too well, it didn't survive the global reach of the Great Depression and the rise of a militarist political order that stifled all artistic endeavor not undertaken in the service of the state. Like the cultural flowering of Weimar Germany, Taisho Democracy proved to be a fragile blossom that was all too quickly nipped in the bud.

All images courtesy of the Hibiya Library & Museum. |

|

| Blooming of Japanese Modernism: Imagerie and Modern Design (in Japanese only) |

| 8 June - 7 August 2018 |

| Hibiya Library & Museum |

1-4 Hibiya Koen, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo

Phone: 03-3502-3340

Museum hours: 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. (to 7 p.m. Saturday and 5 p.m. Sundays and holidays); closed on the third Monday of the month and during the New Year holiday

Access: 3 minutes' walk from Kasumigaseki Station on the Metro Marunouchi, Hibiya and Chiyoda Lines |

|

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for over 30 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|