|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

All That Glitters: The Kanazawa Yasue Gold Leaf Museum

Alan Gleason |

|

Exterior view of the Kanazawa Yasue Gold Leaf Museum. |

As kimonos are to Kyoto, as coal is to Newcastle . . . so is gold leaf to Kanazawa, which produces 99 per cent of the stuff in Japan. Not surprisingly, the city boasts a museum dedicated to gold leaf, showcasing the many arts and crafts that utilize the material as well as the process by which it is made. As a bonus, the Yasue Gold Leaf Museum is located close to the beautifully reconstructed Higashi Chaya district, once one of Kanazawa's most bustling geisha teahouse quarters.

The museum was founded in 1974 by Takaaki Yasue (1898-1997), a local gold leaf artisan who built it to display his collection of gold leaf art as well as the tools used in the material's production. In 1985 he donated the museum to the city of Kanazawa, which moved it in 2010 to the attractive new facility it now occupies. Designed to resemble a traditional Kanazawa storehouse, the building itself makes ample use of gold leaf in its construction.

|

|

|

|

|

Inside the museum entrance.

|

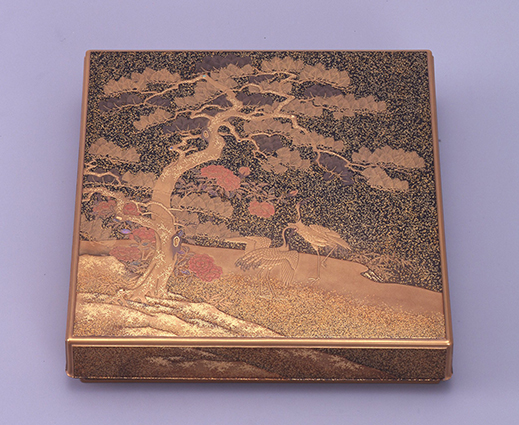

The Yasue collection comprises some 300 works that utilize gold leaf, dating primarily from the Edo period (1603-1867) to the present. Ranging from scrolls, folding screens, and Buddhist altars to lacquerware, ceramics, and Noh costumes, it is a stunning, diverse, and sublimely glittery trove. Besides its permanent exhibit on the gold leaf production process, the museum regularly schedules temporary exhibitions of works from this collection. The current Summer Exhibition, on view until 24 September, is on the theme of "Gold and Silver." The museum offers English-language guide services if you contact them in advance.

Gold leaf, or kinpaku, has long been a mainstay of Japanese art and ornamentation, beginning with its widespread use in decorating Buddhist statuary and altars. Gold was mined in Japan as far back as the Nara period (710-794), inspiring the tales heard by Marco Polo of Zipangu, the "land of gold." The application of gold leaf or powder to fine art reached a zenith during the Edo period, when the Kano school produced glorious gold-backed screen paintings and lacquer artists perfected the techniques of maki-e, lacquerware sprinkled with gold-powder designs.

|

|

|

|

Rakuchu rakugai byobu (pair of folding screens depicting "sights in and around Kyoto"), left (top) and right (bottom) screens, color on paper with gold leaf. Attributed to Iwasa Katsushige (1604-1673), Edo period. |

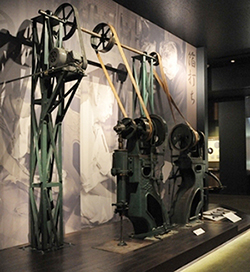

By the late 16th century, the Maeda clan that ruled the wealthy province of Kaga from its castle in Kanazawa had become an avid patron of arts and crafts, turning the city into a mecca for gold beaters and other artisans. Yet it was not until the Meiji era (1868-1912) that Kanazawa grew into the country's premier producer of gold and silver leaf. Under the Edo shogunate, which restricted metal leaf production to Edo and Kyoto, practitioners in Kaga had to pursue their craft clandestinely. But with the fall of the shogunate in the 1860s, Edo stopped producing gold leaf and Kanazawa took up the slack. It is here that the gold leaf hammering machine, or haku-uchiki, was invented in 1915.

|

|

|

|

|

Gold leaf hammering machine in the permanent exhibition room.

|

Though Japan's metal leaf industry suffered during World War II, when the government prohibited the manufacture and sale of "luxury items," it boomed once again in the postwar years. Kanazawa's enduring dominance in gold leaf production is attributed to the city's clean water as well as its humid climate, which is ideal for gold beating (the static electricity associated with dry air is gold leaf's nemesis). The city also produces 100 per cent of the country's silver and platinum leaf.

Minori Yoshita (1932-), Dish with a design of magnolias in yuri-kinsai (underglaze gold), 1995 (on display until 24 September 2018). |

Gold's malleability is such that artisans are able to pound it into translucent layers as thin as 1/10,000 of a millimeter (that's a tenth of a micron!). Even with the use of the hammering machine, it is a painstaking, time-consuming process, as the Yasue Museum's step-by-step exhibits attest. Gold mixed with a bit of silver and copper -- different grades are defined by these alloy ratios -- is thinned with a rolling mill, sandwiched between layers of a special paper prepared in a process nearly as exacting as that of the leaf, and beaten by machine in successive stages as the gold is gradually stretched out to its maximum thinness. The leaf is then cut with a bamboo frame into standard 109-mm squares and stacked amid paper sheets in 100-sheet units. Every stage demands the full concentration of the artisan, because the slightest misstep can turn the leaf into powder.

|

|

The finished leaf is picked up with bamboo sticks and moved from the hammering paper to a notebook, the hiromonocho, for temporary storage. |

The leaf is moved from the hiromonocho to a leather-covered board, on which it is trimmed with a bamboo frame, then transferred to a sheet of haku-aishi, a special handmade paper. The leaf is piled up in stacks of 100 sheets for shipping. |

The applications of gold leaf are myriad: not only architecture, sculpture, painting, ceramics, and lacquerwork, but also cosmetics and -- thanks to gold's chemical inertness -- food. Connoisseurs of fancy Japanese sweets may be familiar with wagashi sprinkled with flakes of gold leaf, but Kanazawa goes them one better with gold leaf-topped ice cream. Stroll down the street from the Yasue Museum to the nearby Higashi Chaya district and you will find shops hawking the world's most luxurious ice cream cones, as well as all manner of gold-coated souvenirs -- even USB drives.

Justly deserving its "Little Kyoto" moniker, Kanazawa is blessed with a plethora of must-see cultural destinations. The Yasue Museum belongs high on the list, offering as it does a thorough introduction to a craft that epitomizes the city's preeminence as a center of traditional Japanese arts rivaling the ancient capital.

|

|

Zuiho Igarashi (1852-1903), Suzuri-bako (writing box) with auspicious design of pine and cranes in maki-e, gold on lacquer, Meiji era. |

All images courtesy of the Kanazawa Yasue Gold Leaf Museum. |

|

| Kanazawa Yasue Gold Leaf Museum |

1-3-10 Higashiyama, Kanazawa, Ishikawa Prefecture

Phone: 076-251-8950

Museum hours: 9:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. (no admission after 4:30); open daily; closed 25 September to 5 October, 26 to 30 November, and 29 December 2018 to 3 January 2019

Access: 10 minutes by bus from JR Kanazawa Station on the Hokuriku Shinkansen Line (2 1/2 hours from Tokyo) |

|

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for over 30 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|