|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Protean Outsider: Isamu Noguchi

Alan Gleason |

|

Wave in space #2 (1968), African granite, The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York (whereabouts: The Isamu Noguchi Foundation of Japan). Photo by Michio Noguchi |

The oeuvre of Isamu Noguchi (1904-88) is so vast and varied that his muse seems to have held him in demonic thrall. Besides his iconic sculptures, Noguchi designed everything from furniture to playgrounds to monuments commemorating atomic holocaust. A retrospective at Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery until 24 September offers a thoroughgoing tour of the man's prolific career that may leave you wondering what drove him.

Noguchi's personal history is so dramatic and fraught that some knowledge of it can't help but shed light on his art. Since birth -- or even before it -- he was doomed to a life of constant upheaval, torn between two highly idiosyncratic and willful parents from radically different cultures. He never completely belonged to either the United States or Japan, and at crucial junctures in his life the two nations were on hostile terms or at war.

|

|

|

|

|

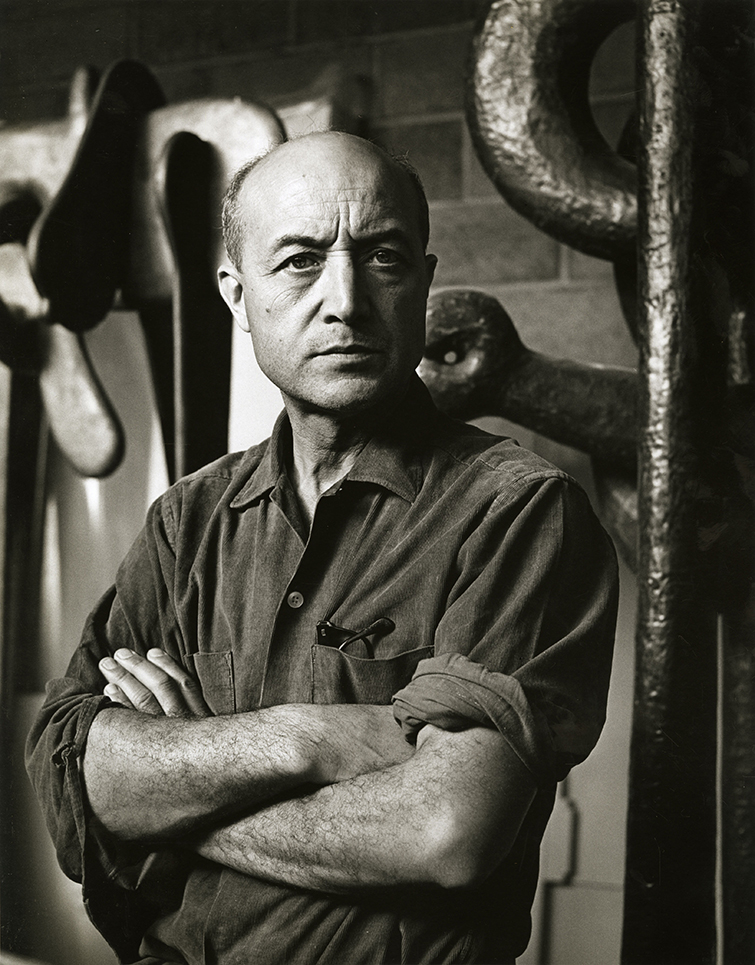

Isamu Noguchi. Photo by Jack Mitchell

|

Noguchi was born in Los Angeles in 1904 to Leonie Gilmour, the American editor and lover of Japanese poet Yonejiro Noguchi, who broke up with Gilmour and returned to Japan before his son was born. Mother and child first went to Japan when Isamu was three, where Isamu met his father for the first time, but the reunion was short-lived -- in the meantime Yonejiro had fathered another child by a Japanese lover. Undaunted, Leonie stayed on in Japan with her son, who attended Japanese schools and by his account had a generally happy childhood in the seaside town of Chigasaki. But his mother, feeling that he would fare better in the long term in his country of birth, sent him off at age 13 to a progressive boarding school in Indiana. She also encouraged his artistic predilections, and after high school Isamu (who went by the name Sam Gilmour during these years) went to work as an apprentice for the sculptor Gutzon Borglum, known for the presidential heads at Mount Rushmore.

|

|

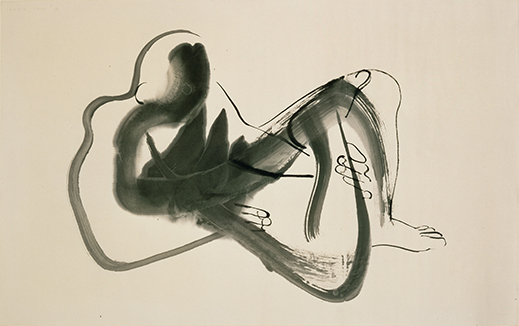

Peking Brush Drawing (man reclining) (1930), ink on paper, The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York. Photo by Kevin Noble |

It was from around this time that Noguchi began to display a fierce and dogged determination to establish himself as an artist despite numerous obstacles and discouragements, starting with Borglum's declaration that he would never be a sculptor. After a brief stint as a premed student at Columbia University, Isamu (again at the urging of his mother) dropped out and devoted himself to sculpture, changing his name to Noguchi. His portrait busts earned acclaim as well as some money, but he was already leaning toward the abstract modernism that would define his greatest work. He also began to travel. Leaving New York for Paris in 1927 on a Guggenheim Fellowship, he studied stone sculpture with Constantin Brancusi for several months. Three years later he set out again from New York, this time to Asia, hoping to see his father. Unfortunately Yonejiro let it be known he did not want his son using the same surname in Japan, so instead Isamu went to Peking, where he studied brush painting. Eventually he did make it to Japan and met his father, who introduced him to a number of artists and literati. Here Isamu also had his first exposure to such seminal influences as Japanese pottery, Zen gardens, and the ancient clay figures called haniwa.

At this point Noguchi appears to have surmounted the turmoil of his upbringing and even found a way to reconcile, through art, his own internal cultural conflicts, absorbing a bewildering array of artistic influences from both East and West that would serve him well for the rest of his life. But his career continued to suffer marked ups and downs. In Depression-era New York he began designing playgrounds, but all of his proposals were rejected and he went back to relying on portrait sculpture for a livelihood. Meanwhile, he started a long and fruitful professional relationship with the pioneering modern dancer Martha Graham, designing abstract stage sets featuring interlocking sculptures made of balsa wood.

|

|

Martha Graham in Herodiade, with the set design by Isamu Noguchi (1944). Photo by Arnold Eagle |

Then came the war. As a resident of New York, Noguchi was not forced into an internment camp, but he voluntarily entered Poston Camp in Arizona in an effort to improve living conditions by building parks and playgrounds. There he found himself treated as a nuisance by the War Relocation Authority, and with distrust by internees who viewed him as an outsider and possibly a government spy. After some months he was granted permission to return to New York, but not before the FBI had investigated him on suspicion of espionage for Japan. The experience surely marked the nadir of Noguchi's life as a man without a country to call his own.

Yet with the war's end, Noguchi launched himself on the trajectory that led him to the pinnacle of recognition as one of the greatest sculptors of the 20th century. Things began looking up when he returned to Japan in 1950, this time to a warm welcome by the country's artistic establishment. He was invited to design monuments for Hiroshima's Peace Memorial to victims of the atomic bomb, though his proposal for the central cenotaph was rejected at the last minute due to his American citizenship. However, two bridges of his design still stand in Hiroshima, and overall, his Japan sojourn was a triumphant one.

|

|

Sunken Garden for Chase Manhattan Bank Plaza (1961-64), New York City. Photo by Arthur Levine |

Perhaps the high-water mark was a project he undertook for Keio University, where his father (who died in 1947) had taught for 40 years. Noguchi was introduced to the architect Yoshiro Taniguchi, who later designed the renowned Hotel Okura lobby. The two collaborated on the Banraisha, a building on Keio's Tokyo campus that was to serve as a faculty retreat (the original had been destroyed in the firebombing of 1945). Taniguchi's plan, all straight lines in concrete, provided a stark backdrop to Noguchi's curvy designs for the lounge and garden, as well as the sculptures to be placed there. The lounge, later dubbed the Noguchi Room, was a tour de force of modernist Western and traditional Japanese motifs. Its centerpiece was a circular fireplace with an overhead flue that itself was a masterpiece of abstract sculpture. Noguchi divided the space into three sections, which he said represented Life on Tatami, Life on Chairs, and Life in Shoes -- the last epitomizing the between-homelands limbo in which the artist found himself, a state of mind he may have identified with more closely than with either country.

In a travesty of short-sightedness rivaling the demolition of Frank Lloyd Wright's Imperial Hotel, Keio University dismantled the Banraisha to make way for a new building in 2006, though a part of it was relocated to the rooftop garden of another building on the campus. Fortunately there is an extensive photographic record of the Banraisha, allotted its own corner of the current exhibition, that testifies not only to Noguchi's protean genius but also to the brilliance of this collaboration between two giants of architecture and design.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Love of Two Boards (1950), Seto stoneware, The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York. Photo by Kevin Noble

|

|

Beppin-san (1952), Seto stoneware, hemp, The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York. Photo by Kevin Noble |

Until he left Japan in 1953, Noguchi was a veritable whirlwind of activity. He visited a number of the country's great pottery centers, producing stoneware sculptures with a whimsical resemblance to his beloved haniwa figures. He married a popular Japanese actress (herself an outsider who had grown up speaking Chinese in Manchuria), though they divorced a few years later. His immersion in traditional Japanese arts -- architecture, ceramics, gardens -- during this period sharpened the focus of his artistic vision for the remainder of his career. Now enjoying adulation in both Japan and the US, he increasingly functioned as a bridge between the cultures, designing a Zen-inspired rock garden for New York's Chase Manhattan Bank in the early sixties and, in 1965, finally receiving his first playground commission for Kodomo no Kuni, a vast children's park in the Yokohama hills. He even made a splash in furniture design with his legendary Akari series of "light sculptures" -- lamps of paper, wire and bamboo that continue to be in demand today.

|

|

AKARI (1953-), paper, bamboo, metal, The Kagawa Museum. |

But for all his irrepressible ventures into multiple media, Noguchi was first and foremost a sculptor. Late in life he began to favor hard stones like granite and basalt as his sculpting materials, producing a series of stunning works in which he applied the chisel with a light hand, accenting and extracting the inherent beauty and spirit of the stone rather than shaping it into images of his own intent. The title of one such work, The Stone Within (at the Noguchi Museum in Long Island City), references Michelangelo's famous remark that a sculptor's job is to find the sculpture already latent in the block. These later works, among the most powerful in the Tokyo exhibition, appear at the end of the series of galleries as a satisfying denouement to Noguchi's variegated career.

The show is not strictly chronological, nor does it provide much information about Noguchi's life early on. So it is with some relief that one exits the last gallery to find an exhaustive timeline extending several meters down the hall. Here at last we are able to fill in the gaps and discern some continuity in his tumultuous history. Ironically, though, there is very little English text to be found in the show, aside from work titles and credits. Granted, preparing non-Japanese text puts a heavy budgetary burden on Japanese museums, but it's still a pity that visitors who cannot read Japanese are deprived of the in-depth commentary on Noguchi's life and art supplied by the detailed captions and timeline -- all the more because the subject at hand is an artist whose bicultural identity shaped his work from the outset.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Archaic (1981), basalt, The Kagawa Museum. Photo by Akira Takahashi

|

|

Untitled (1987), Indian granite, The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York (whereabouts: The Isamu Noguchi Foundation of Japan).

Photo by Akira Takahashi |

All images are courtesy of Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery. All works shown are by Isamu Noguchi, © The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York / Artist Rights Society [ARS] - JASPAR. |

|

| Isamu Noguchi: from sculpture to body and garden |

| 14 July - 24 September 2018 |

| Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery |

Tokyo Opera City 3F, 3-20-2 Nishi-Shinjuku, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo

Phone: 03-5777-8600 (NTT Hello Dial)

Open 11 a.m. to 7 p.m. (to 8 p.m. on Friday and Saturday); entry up to 30 minutes before closing

Closed Monday (Tuesday if Monday is a public holiday), year-end/New Year holidays, and exhibition changeover and maintenance days

Access: 5-minute walk from east exit of Hatsudai Station on the Keio New Line (one stop west of Shinjuku Station) |

|

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for over 30 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|