|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Looking for the Rimpa Legacy in Present-day Nihonga at the Sato Sakura Museum

Alan Gleason |

|

Koichi Nabatame, Chrysanthemum and the Rising Sun (1999) |

Say "Rimpa" and most art enthusiasts think of Ogata Korin's celebrated Irises or the iconic Fujin-Raijin screen paintings of the Wind and Thunder Gods by Korin (1658-1716) and his predecessor Tawaraya Sotatsu (ca. 1570-1640). Rimpa is not really a school, but a style developed in the Azuchi-Momoyama and early Edo periods, not so much passed down as picked up by sympatico artists of succeeding generations. It did not even have a name until Rin-pa, an abbreviation for "Korin school" after its most famous practitioner, caught on after it appeared as the title of a major Tokyo National Museum exhibition in 1972.

Though there is no fixed definition of the Rimpa style, its exemplars tend to favor large, multi-panel screen paintings covered with gold leaf, bright (some would say gaudy) colors, highly decorative motifs -- particularly of flowers and birds -- and rhythmic, repeating patterns. The aforementioned Irises is often cited as the ultimate example of the use of such patterns: Korin famously used stencils to reproduce the same irises over and over in this monumental work.

|

|

Nobuyoshi Watanabe, Opium Poppy (1994) |

The Sato Sakura Museum in Nakameguro, Tokyo currently has an intriguing show, Rimpa to Nihonga, that seeks out the Rimpa influence in contemporary Nihonga. Since Nihonga is a concept just as slippery as Rimpa, this is not as self-evident as it may sound. The term, literally "Japanese painting," was coined in the late 19th century by proponents of art that employed traditional Japanese techniques and materials (mineral pigments, handmade paper, calligraphic brushes) in a conscious rebuttal to the Meiji-era influx of Western styles and methods. Nowadays, however, Nihonga of every conceivable genre can be seen, from nudes and landscapes to abstract expressionism; the only characteristic distinguishing them from Western art appears to be the continued affinity for homegrown materials.

|

|

Installation view, Rimpa to Nihonga exhibition. From left to right: Jun'ichi Hayashi, Red and White Plum Blossoms (2000); Matazo Kayama, Hazy Moon (1996, partially hidden); and Reiji Hiramatsu, Way - Wild Chrysanthemum (1996) |

Naturally Rimpa is one of the traditions carried over into Nihonga, so it is not really difficult to find evidence of its legacy in the work of Nihonga artists of the last 30 years, the generation highlighted in this show. The oldest work on display is a 1970 painting by Matazo Kayama (1927-2004), often hailed as the 20th century's foremost heir to the Rimpa line. Kayama did not label himself as such, though he is quoted as having found inspiration in the gorgeous gold and silver screens he saw at a Rimpa exhibition during Japan's impoverished postwar years. Similarly, the other artists selected here are said, in the museum's words, to belong to the Rimpa lineage "consciously or unconsciously."

The curators make a noble effort to systematically identify the elements in these paintings that suggest a Rimpa link. The show is divided into sections that bring together works featuring particular Rimpa attributes, such as the design-like repetition of rhythmic patterns, the use of gold and silver backgrounds, and recurring motifs revisited by succeeding generations of artists.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

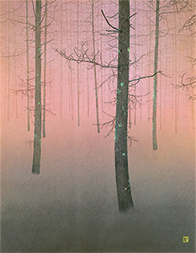

Yuji Sasaki, Winter Pine Forest at Daybreak (1992)

|

|

Masako Kaneki, Cats Pattern - Winter (2014) |

The Rimpa predilection for repetition is noted, for example, in the work of Yuji Sasaki, who depicts a stand of trees receding into the misty distance in Winter Pine Forest at Daybreak; Mitsuei Saito, in whose Goldfishes a multihued school of fish swims across a silvery background; and Masako Kaneki, who offers a gaggle of felines in her self-explanatory Cats Pattern - Winter. The museum's preference for large-scale works heightens the dramatic impact of the show as one passes from gallery to gallery. And though the coloring sometimes borders on the flashy and ornate, that is of course a Rimpa hallmark. As befits the style's decorative aspects, the artists' technical prowess is without exception impeccable.

Mitsuei Saito, Goldfishes (2017) |

Yuji Tezuka, Precious Spring (1995) |

Originally founded in Koriyama, Fukushima Prefecture in 2006, the Sato Sakura Museum relocated to Tokyo in 2012. Recently it expanded even further, opening the Sato Sakura Gallery in New York's fashionable Chelsea district in 2017. The Tokyo building, a compact, three-story cube, is a stunning presence on an otherwise nondescript back street, faced as it is with a black grid of 1,100 perforated tiles bearing the museum's logo, an abstraction of a cherry blossom petal. By day this façade seems a bit opaque and impassive, but at night, illuminated from within, it's sublime. It also sets up a pleasantly surprising contrast with the interior, whose three floors of galleries are warmly lit and connected by tiers of attractive wood-floored hallways and staircases.

|

|

|

|

|

The façade of the Sato Sakura Museum in Nakameguro, Tokyo

|

The Nakameguro site is ideal for a museum named for the famous blooming cherries of its Fukushima birthplace (Sato Sakura literally means "homeland cherries"): it sits close by the cherry-lined Meguro River, a favorite blossom-viewing spot in the spring. Specializing in contemporary Nihonga, in which cherry blossoms are a popular motif, the museum naturally has an extensive collection of sakura-themed works. In addition to several cherry trees that appear in the Rimpa to Nihonga show, the museum's concurrent 100 Views of Sakura exhibition features the blossoms in profusion. The present iteration of this rotating series, "Vol. 15," showcases a dozen such works painted in the last decade. If you can't wait till spring to get your cherry-blossom fix, this is the place to go.

Chinami Nakajima, Spring Night, a Weeping Cherry Tree in Miharu (1998) |

Kiwako Suzuki, Invitation (2013) |

All images courtesy of the Sato Sakura Museum. |

|

| Rimpa to Nihonga (in Japanese only) |

| 4 September - 25 November 2018 |

| Sato Sakura Museum (in English) |

1-7-13 Kamimeguro, Meguro-ku, Tokyo

Phone: 03-3496-1771

Open 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. (last admission at 5:30 p.m.)

Closed Mondays (except public holidays), year-end/New Year holidays, and during exhibition preparation periods

Access: 5-minute walk from Nakameguro Station on the Tokyu Toyoko and Tokyo Metro Hibiya Lines

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for over 30 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|