|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Contemporary Art with Something to Say: 25 Taro Award Winners

Alan Gleason |

|

|

The Taro Okamoto Award for Contemporary Art is named after one of postwar Japan's most celebrated artists. Okamoto was a self-styled maverick who enjoyed unsurpassed notoriety in his lifetime thanks to his ubiquitous public sculptures, frequent TV appearances, and outspoken views on social issues. Blending elements of cubism, abstract expressionism, and pop art in his highly accessible oeuvre, he was Japan's Picasso, Pollock, and Warhol rolled into one. Two Tokyo-area museums are dedicated to his work: one is his former atelier in Aoyama, the other a larger facility in Kawasaki, just south of Tokyo. (See Here and There here for an introduction to Okamoto's work and there for a previous review of a show at the Kawasaki venue.)

Each year the Taro Award competition offers prizes to several artists selected by a panel of critics, scholars, and curators, including the directors of the two museums. Their stated mandate is to "honor artists who have inherited Taro's will to present sharp messages to society based on unfettered ideas and unique viewpoints." Established soon after Okamoto's death in 1996, the competition is now in its 22nd year. This year it attracted 416 submissions from which it chose 25 winners, five of whom received the top prizes: the Taro Okamoto Award, the Toshiko Okamoto Award (named after Taro's daughter), and three Special Awards. All 25 works are on display at the Taro Okamoto Museum of Art, Kawasaki, until 14 April. An exciting and provocative assemblage, it is one of the most enjoyable contemporary art shows I have seen.

True to the judges' mandate, the winning works have a lot to say about contemporary society, but they are also imaginatively conceived and executed, and often extremely funny. Social criticism with a sense of humor: what's not to like? The high entertainment quotient is something Taro himself would certainly approve of.

I found something of interest in every one of these works, but since it would take up a bit too much space to introduce all 25, I will focus on a half-dozen or so that were particularly compelling.

|

|

Kazuhiko Hiwa (seen at right), hiwadrome: type ZERO spec3, wheelchairs, LED lamps, projectors, LCD monitors, etc. |

Kazuhiko Hiwa took the top Taro Award for hiwadrome: type ZERO spec3, an installation that occupies an entire room. Dominating the space is a monstrous black sci-fi contraption festooned with swiveling, blinking LED lamps, like a Christmas tree from hell. On closer inspection, the "tree" turns out to be a jumbled heap of black wheelchairs. Amid the eerie red glow that bathes the room, videos playing across the walls show a man with stunted arms and legs cheerfully performing calisthenics and other physical activities with a more conventionally "abled " partner. The first man is the artist himself, who has successfully parlayed his disability into art without betraying an ounce of self-pity or self-aggrandizement. Hiwa was there the day I visited, scribbling energetically on the walls in a live-painting performance, very much a part of his own installation.

Miss Revolutionary Idol Berserker, Lump of Berserker, electric spectaculars, projectors, monitors, DVD player, guitar, etc. |

Another room-sized entry is Lump of Berserker, the over-the-top fever dream of an artist who goes by the moniker Miss Revolutionary Idol Berserker (Kakumei Idol Boso-chan). Her concept is to stand the squeaky-clean image of Japan's pop-idol industry on its head. The room is a cacophony of posters, banners and other paraphernalia touting a band of punkish, bad-attitude anti-idols modeled, it seems, after the country's boso-zoku hot-rod gangs. What makes the installation extra fun is that you are invited to enter and trample the piles of newspaper and magazine clippings that litter the floor, and to pose as an "idol berserker" yourself by sticking your head through one of those photo-op panels seen in amusement parks.

Kazunori Takeuchi, When an east wind is played (Bottchi in Kawasaki), ceramics, cedar twigs, wires, etc. |

Kazunori Takeuchi's When an east wind is played (Bottchi in Kawasaki), a Special Award recipient, is an enigmatic work that grabs your attention the moment you walk into the main exhibition gallery. Large ceramic heads, cut off at the neck, squat on the floor, grinning up at the beholder. Behind them rises a thicket of withered branches. The first impression is of ancient Chinese statuary -- Buddhas, perhaps -- but the expressions on the faces are anything but beatific. The artist's essay in the exhibition pamphlet offers an unexpected explanation (my translation): "The human effigies emerged from the shame I felt at human folly in the wake of the nuclear meltdowns [in Fukushima]. This work is both a hymn for the oppressed and a warning to humanity. Nature is watching us, but with a scornful laugh." Bottchi, incidentally, are urns used to dry peanuts outdoors in the artist's native Chiba.

|

|

|

|

|

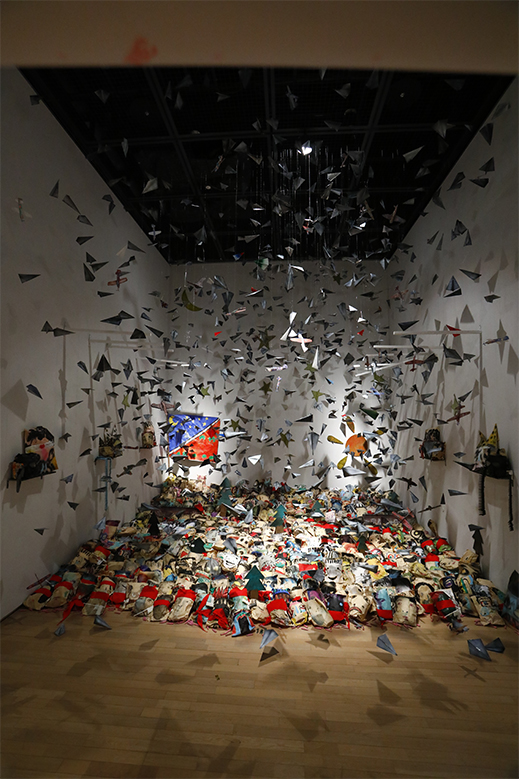

Ma Jiahao, Legion of Child Country, envelopes, plastics, watercolors, books, spray, etc.

|

More direct in its messaging is Ma Jiahao's Legion of Child Country -- though again, the message may not be quite what you think. Large paper envelopes, each with a red hat and a childlike face drawn on it, cover the floor, while hundreds of plastic airplanes, suspended from wires, hover in the space overhead. Toy soldiers and bullets are strewn everywhere. But what would appear to be a tableau of children at the mercy of war is not exactly that. Writes the artist, who hails from China and is currently studying art in Japan: "As long as adults pass their prejudices against other countries on to their children, there will never be peace. What we need is a children's revolution so they can live together in a country free of prejudice. For that they need an army, so I have created 1,000 soldiers and 500 fighter jets to protect the children's revolution from adults." Whew.

Yuji Honbori, One man's trash is another man's treasure, used cardboard boxes, wood, etc. |

Decidedly more meditative is an awesome construction of a Buddhist temple, complete with statuary, made entirely out of cardboard. Yuji Honbori titles his tour de force One man's trash is another man's treasure. The centerpiece is a triad of Bhaishajyaguru (Yakushi), the Buddha of medicine, and two flanking bodhisattvas, surrounded by twelve protective deities, the "Heavenly Generals." The gaps in the cardboard allow light to pass through from behind, creating a halo effect; from the side, one can see the brand names on the discarded boxes from which Honbori built this corrugated sanctuary.

Sayaka Miyata, MRI SM20110908, sewing yarn |

Sayaka Miyata's beautiful installation consists of six oval, multihued, seemingly abstract creations of yarn suspended in midair. As the title reveals, however, MRI SM20110908 is actually a series of MRI images of her own brain, overlaid by machine-generated embroidery. Miyata says that she intentionally programs "bugs" into the embroidery data to produce random patterns.

And then there is Yoshiki Tanaka's SUPER OLYMPIC, a monumental, gloriously zany construction consisting of what he describes as "three burning temples, sculptures of 101 doggies, various things." His pamphlet comments are so Dadaist as to be incomprehensible, but they reference both the Tokyo Olympics and Kinkakuji, the Golden Pavilion that was burned down by a deranged monk in an incident made famous by Yukio Mishima's eponymous novel. He does not explain the doggies (see the installation view below).

|

|

Installation view: at left is Yoshiki Tanaka's SUPER OLYMPIC, at right is Makiko Tanikawa's October, under the Keyaki (Repeated, unchanged things), and at right rear is Ayano Yoshida's Layer. |

Unfortunately for non-Japanese readers, the comments I have quoted here only appear in the pamphlet in Japanese. But even without access to such aids to understanding the intent behind the works, they are easy to appreciate on their own terms, as I did before reading the artists' notes much later. Viewing this exhibition should give anyone a jolt of positive energy -- not only because of the wildly imaginative work on display, but because of the way it confronts the madness rampant in the world today with such humor and panache. Where there is art, there is hope.

All images courtesy of the Taro Okamoto Museum of Art, Kawasaki. |

|

| The 22nd Exhibition of the Taro Okamoto Award for Contemporary Art |

| 15 February - 14 April 2019 |

| Taro Okamoto Museum of Art |

7-1-5 Masugata, Tama-ku, Kawasaki, Kanagawa Prefecture

Phone: 044-900-9898

Hours: 9:30 a.m. to 5 p.m., last entry 30 minutes before closing

Closed Mondays (or Tuesday when Monday is a national holiday), the day after national holidays, and year-end holidays

Access: 17 minutes' walk from the south exit of Mukogaoka-Yuen Station on the Odakyu Line, 20 minutes from Shinjuku by express

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for over 30 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|