|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Things That Went Bump in the Night: Yokai Get Their Due in Kawasaki

Alan Gleason |

|

Yoshitoshi Tsukioka, Night Parade of One Hundred Demons, 1865, woodblock print. |

What's not to like about yokai? Now that we don't believe in them anymore, they're just funny and cute, cartoon characters with a dollop of grotesquery and occasional horror. But it was not always so. As the Kawasaki City Museum's exhibition Yokai/Human: The Transition from Fantasy to Reality makes clear, people and yokai have had a complicated, evolving relationship since time immemorial -- and not so long ago, they were a real presence in many Japanese lives.

To quote from Yokai Attack!, Matt Alt and Hiroko Yoda's definitive (and very entertaining) English-language treatise on the subject, yokai are "mythical, supernatural creatures that have populated generations of fairy tales and ghost stories." Their ranks include wraiths and monsters, to be sure, but what makes yokai such a fascinating topic of study is their sheer variety and novelty -- a cornucopia of nightmares brought to life. Many are human figures with certain unique traits, like Futakuchi Onna, a beautiful woman with a second mouth in the back of her head, fed by her Medusa-like strands of hair. Or Kamikiri, a ghoul who cuts your hair off when you least expect it. Foxes figure largely in the yokai ranks due to their ability to assume human form for mischief-making purposes. And then there are yokai who take the shape of household furnishings, toiletry articles, musical instruments, and other inanimate objects -- the list goes on and on.

|

|

Yoshifuji Utagawa, Strange Story of Kamikiri (the Hair-cutting Monster), 1868, woodblock print. |

Few yokai are benign in intent toward mere mortals, but they vary in degree of malevolence from deadly to merely irksome. Some are content to jump out at you from behind a bush, just to freak you out. Others shove you underwater until you drown. Essentially, yokai represent a graphic compendium of every scary sight or sound the human imagination has encountered in the dark of night.

In Japan, where large swathes of the predominantly rural country lacked electric lighting well into the 20th century, yokai legends have been remarkably tenacious. Tales of encounters with creepy creatures were a mostly oral tradition until the Edo period (1603-1867) brought literacy and printing to the masses, codifying yokai in visual form through ukiyo-e and other media. Though the new print culture generated something of a yokai boom, it also diluted the fear quotient, making these once-fearsome entities familiar and even endearing.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

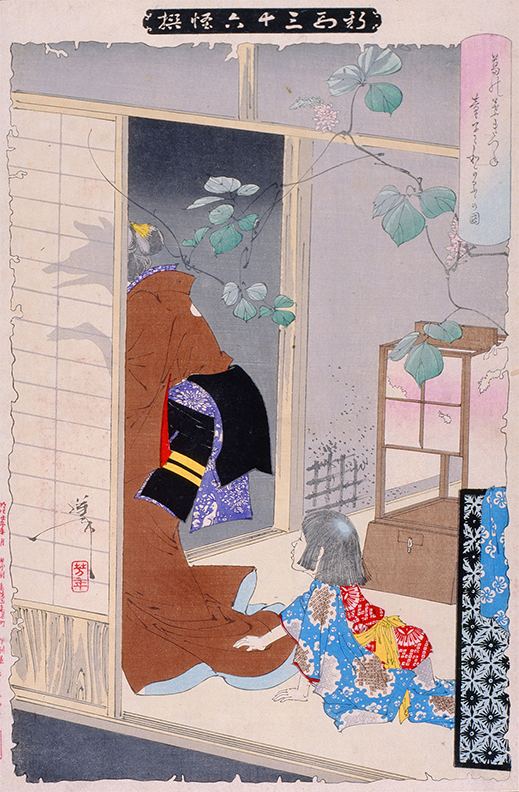

Yoshitoshi Tsukioka, The Fox-Woman Kuzunoha Leaving Her Child, from the series 36 Ghosts, New Selection of 36 Apparitions, 1890, woodblock print.

|

|

Toyokuni Utagawa III, Ku Fire Brigade, Fifth Group, Yotsuya: Actor Bando Hikosaburo V as the Ghost of Oiwa, from the series Flowers of Edo and Views of Famous Places, 1863, woodblock print. |

Nonetheless, until Japan began to embrace modernization and empirical thought in the Meiji era (1868-1912), it's probably safe to say that ghosts, goblins and other supernatural phenomena enjoyed considerable credulity with the public at large -- so much so that late-19th century reformers attempting to bring Japan up to date made it part of their mission to refute such superstitions. At the turn of the century the scholar and Buddhist philosopher Enryo Inoue published a number of tomes on "yokai studies" in which he analyzed and debunked the myriad apparitions haunting the Japanese imagination. His work was made more difficult, though, by the sensationalist newspapers of the day, which were still trumpeting "true" ghost stories as part of their daily fare, much as American tabloids regularly trot out UFO and Elvis sightings.

|

|

|

|

|

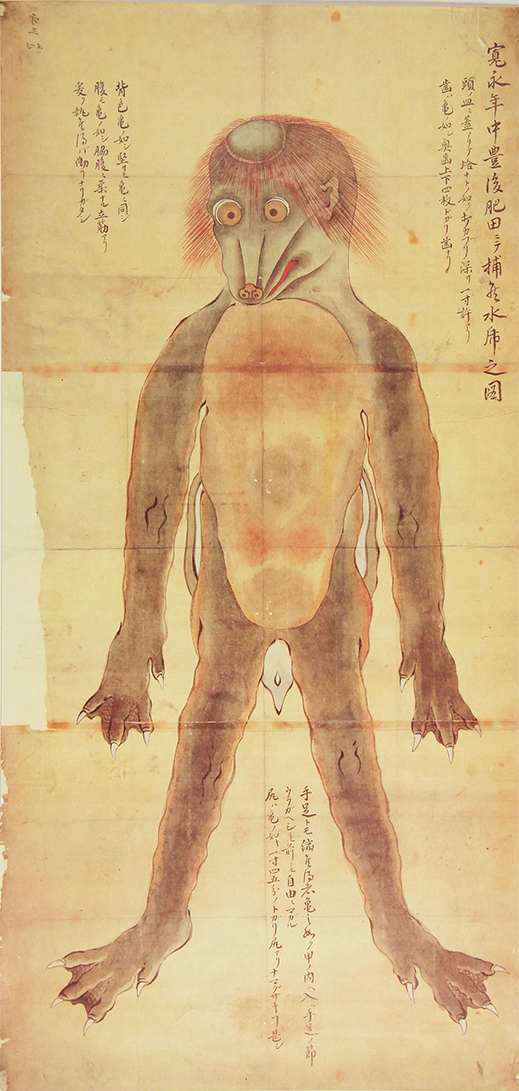

Suiko [Kappa] Captured in Hita, Bungo Province in the Kan'ei Era, late Edo period. |

The Kawasaki show does a thorough job of leading us through these transitions in the yokai's status in Japanese consciousness, although it takes a rather meandering approach. The first section is devoted to the kappa, inarguably the best-known yokai of all. A mischievous, sometimes dangerous water imp, humanoid but with frog-like features and a dish-like depression in its head that holds water, the kappa has long been blamed for all manner of mishaps related to ponds and rivers. Ryunosuke Akutagawa even wrote a famous allegorical novel about a land populated by the creatures. But what cemented the kappa's place in the popular imagination well into the postwar era was Kon Shimizu's 1950s manga series Kappa Kawataro, whose amphibious characters displayed all-too-human foibles, particularly those involving relations between the sexes. Though Shimizu's kappa were a vehicle for social satire, they also endeared these yokai to a generation of manga readers.

No doubt for this reason, the exhibition starts off with a gallery of panels from Kappa Kawataro and its sequel, Kappa Tengoku. Though these are amusing, the real eye-grabber on the wall is a large, clinically detailed rendering of a kappa drawn by an anonymous artist in the 1600s based on a "real specimen" captured in a Kyushu river. The West has its Bigfoot, Japan had (and who knows, may still have) its kappa.

|

|

|

|

|

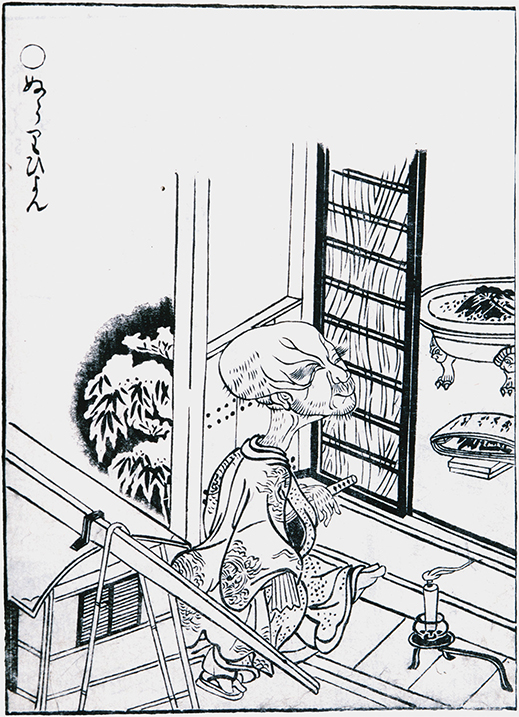

Toriyama Sekien, The Illustrated Night Parade of One Hundred Demons, 1776, illustrated book, woodblock-printed. |

From this point the show progresses more or less chronologically through the Edo period, when ukiyo-e artists found a mass audience for printed illustrations of yokai that had previously appeared only in hand-drawn emaki scrolls. The oft-depicted legend of the Hyakki Yagyo (Night Parade of a Hundred Demons) inspired the 18th-century artist Toriyama Sekien to publish several illustrated compendia of yokai that were instrumental in defining their identities in the public eye.

Yokai also became a tool for satirizing current political events under the censorious gaze of the Shogunate. Sometimes the parodies were hardly subtle: Kuniyoshi's 1843 ukiyo-e The Earth Spider Generates Monsters at the Mansion of Lord Minamoto Yorimitsu, which showed an army of demons about to consume a sleeping Heian-era nobleman and his clueless bodyguards, was widely viewed as a critique of a government increasingly oblivious to the people's needs. It did succeed in rousing the Shogunate to put the artist and his publisher on trial. Political commentary aside, Kuniyoshi, Yoshitoshi, Hokusai and other 19th-century artists churned out reams of yokai-themed prints of the horror-show variety, and the public lapped them up. Another popular sub-genre was imagery of the Buddhist hells, whose denizens suffered gruesome torments at the hands of demons that had much in common with the more vicious yokai. Interestingly, this fascination with the supernatural and the macabre reached its peak just as the Shogunate was collapsing and Western notions of scientific rationalism began to have an impact on the collective Japanese unconscious.

|

|

Kuniyoshi Utagawa, The Earth Spider Generates Monsters at the Mansion of Lord Minamoto Yorimitsu, ca.1843, woodblock print. |

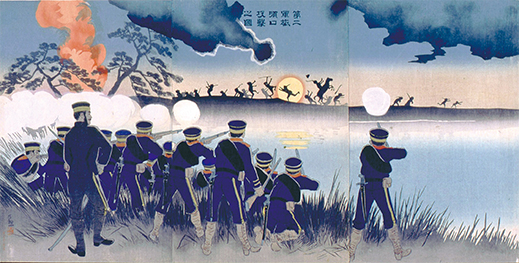

Through its commentaries and choice of displays, the show does a good job of placing this evolution in public perceptions of yokai within the historical context of Edo-era urbanization, followed by Meiji-era modernization. Toward the end, however, it veers in a slightly odd direction as it attempts to link depictions of supernatural phenomena with those of an entirely different subject, Japanese soldiers at war. As yokai art began to lose its cachet in the modern age, the curators posit battlefield art as its heir, arguing that a new genre of ukiyo-e showing gallant troops demolishing their Chinese or Russian adversaries (Japan went to war with China in 1894 and Russia in 1904) was in some way an extension of portrayals of violence at the hands of specters and demons. As the exhibition's title suggests, modern technology had allowed humans to replace yokai as agents of fear and destruction. Granted, these works of war propaganda share yokai art's preoccupation with violence and gruesome death -- but instead of attacks by ghosts, demons and spidery monsters, we get riflemen picking off hordes of faceless Chinese, identified only by their pigtails. If there is a meaningful similarity between the two genres, it is in their representation of the adversarial "other" as a non- (or sub-) human entity devoid of personal identity. Once in a while, the ghost of a fallen soldier or assassinated leader hovers in the air, but that is the extent of the continuity between these war-glorifying images and the yokai paintings of yore.

|

|

Kiyochika Kobayashi, The Japanese 2nd Army Attacks Port Arthur, 1894, woodblock print. |

Still, it is impressive that the Kawasaki City Museum owns enough work in either genre to cobble together an exhibition of this size and substance. According to curator Mitsuha Furuie, one of the museum's longtime curators was a yokai specialist who amassed a sizable collection that this show taps into; the subject matter also dovetails with the museum's other strengths in manga, print art, and folklore.

The museum is, in fact, a rather unusual facility in that its art galleries share the building with an extensive permanent natural history exhibition detailing the city of Kawasaki's development since ancient times. This gives its curators access to an impressive trove of items spanning the fine arts, crafts, and ethnology that lend themselves to cross-disciplinary exhibitions like the yokai show.

Kawasaki itself is a unique city. Just across the Tama River from Tokyo, it occupies a long narrow strip of riverside lowland whose fertility has made it a favored human habitat since prehistoric times. Hunting and fishing gave way to rice cultivation; then, during Japan's postwar high-growth era, Kawasaki became a factory town notorious for its pollution-belching smokestacks. Now the foundries and refineries have been largely replaced by hi-tech R&D parks and suburban subdivisions. The area's long and variegated history makes for a fascinating series of exhibits that are well worth exploring after you've been thoroughly spooked by the yokai.

|

|

A gargantuan Thomas Smelting Furnace dominates the plaza of the Kawasaki City Museum. A relic of the city's industrial heyday, it was installed in the Nippon Kokan (now JFE Steel) company's Kawasaki foundry in 1937. |

All images are courtesy of the Kawasaki City Museum. |

|

| Yokai/Human: The Transition from Fantasy to Reality |

| 6 July - 23 September 2019 |

| Kawasaki City Museum |

1-2 Todoroki, Nakahara-ku, Kawasaki, Kanagawa Prefecture

Phone: 044-754-4500

Hours: 9:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. (admission until 4:30 p.m.); closed Monday (or the following Tuesday when Monday is a national holiday) and during the New Year holidays

Access: 10 minutes by bus from Musashi-Kosugi Station on the Tokyu Toyoko Line and the JR Nanbu and Yokosuka Lines

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for over 30 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|