|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Passing the Baton: Art and Community at the Nakanojo Biennale

Alan Gleason |

|

The former Gotanda School, a single-story wooden building that local residents built themselves in 1909. The school closed in 1969 but now serves as a community center. This month it hosts installations by eight Nakanojo Biennale artists. |

Sometimes it seems that Japan has more Biennales and Triennales than you can shake a stick at. The economic boost brought to depressed, depopulated areas by big-ticket art festivals like the Echigo-Tsumari and Setouchi Triennales has inspired a spate of similar productions around the country.

The most visible of these are sustained by the deep pockets of corporate or government sponsors, but there are some exceptions. One of the more remarkable successes is the Nakanojo Biennale. Held in the mountainous Agatsuma River valley of Gunma Prefecture, it has grown from a virtually one-man undertaking into a sprawling event that rivals better-known festivals in scale as well as visitorship. Founded in 2007 by Tokyo-based designer Tetsuo Yamashige, the event celebrates its seventh iteration this year with a roster of 150 artists and art units -- 50 from outside Japan -- exhibiting at over 50 venues scattered across the steep hills and deep valleys of Nakanojo, a town whose 17,000 residents occupy barely a fraction of its 440 square kilometers.

|

|

In Australia-based Mika Nakamura-Mather's Singing Ringing Memories 2019, a classroom in the Gotanda School echoes with the sound of bells striking ema -- wooden votive plaques on which 350 residents wrote down their recollections of growing up in Nakanojo. |

Open until 23 September, Nakanojo Biennale 2019 promises to surpass the 470,000 visitors it drew in 2017, and without benefit of the publicity that heavily hyped projects like Echigo-Tsumari and Setouchi receive. What it lacks in big-name artists and corporate backing, however, it makes up for through the active networking Yamashige and his team engage in with like-minded art festivals in other countries, notably in Europe and East Asia. Nakanojo also benefits from relative proximity to the Tokyo metropolitan area -- it is only two hours by train or car from the capital.

|

|

Nobuo Mitsunashi's Chikato Shrine Hypothesis Garden fills the precincts of an ancient Shinto shrine at the foot of sacred Mt. Takeyama with geometric, stupa-like sculptures made of unglazed ceramic plates. |

The Nakanojo Biennale began as Yamashige's brainchild. As a Tokyo art student, he and his classmates came to Nakanojo on a retreat held in an old wooden former schoolhouse. Yamashige fell in love with the region, a place of verdant, slow-paced mountain hamlets known for an abundance of hot springs but suffering the effects of depopulation and economic depression endemic to rural Japan today. Some years later, as director of his own design studio, Yamashige corralled a number of artist friends into helping him set up the first Nakanojo Biennale. From the outset, he says, he was determined to engage local residents in the festival. The country-city interaction is two-way, as artists from Tokyo and elsewhere set down roots in the community during long-term residencies -- some moving here permanently, as Yamashige and his family did -- while Nakanojo citizens actively help produce and promote the biennial event, as well as keep local arts-related activities going in the off years.

|

|

In Kazue Iwatsuka's It was knitted - What will be inherited, a woven net of red thread cascades like a river of blood over a tatami-mat parlor in the 160-year-old Yamase mansion, an Edo-era lumber merchant's residence. |

Until the festival's expansion made a one-man operation infeasible, Yamashige did most of the legwork, even personally selecting the artists from among the 300-plus open-call applicants. Nowadays, he says, he has a team of jurors to handle the selection process, as well as a staff of 15 to run the festival. "We make our choices based on the artist, not the work," he adds. "We pick artists we think are meaningful to have here, and trust them to present work that is meaningful to have here."

One of the great charms of this Biennale is its use of historic buildings that might otherwise have been demolished. Nakanojo has seen most of its elementary and junior high schools shut down in the last decade or so, but residents have fought to keep such facilities intact for use as community centers, arts and crafts studios, and the like. One beautifully preserved Meiji-era schoolhouse is now the local museum; a sake brewery that went out of business hosts Biennale art installations, and so does the terminal of an abandoned mine railway.

|

|

German artist Florian Goldmann has installed Modeling Catastrophe - A Test Arrangement III -- a scale model of the damaged Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Plant, meticulously replicated by a German pensioner -- in a traditional Japanese-style room in the Yamase house. Photo by Florian Goldmann |

It is this active community involvement that sets Nakanojo apart from other Triennales and Biennales that have been known to take over entire islands like an invading army, build museums by star architects featuring the work of star artists, and even convert whole villages into installations. Nakanojo's local spirit is nowhere more obvious than in Shima Onsen, a village high up a long mountain valley that has seen better days despite boasting a historic hot-spring resort. When the village's only elementary school closed down in 2005, residents formed a nonprofit organization to preserve the Meiji-era wooden structure and convert it into a community center. It was fortuitous timing that brought the first Biennale to Nakanojo just two years later, and since then the former Daisan Elementary School has been the flagship venue for art installations in Shima Onsen.

|

|

Motoko Hoshi's installation in the Daisan Elementary School building in Shima Onsen. "Baton" mobiles, suspended by rubber bands that expand and contract, dance silently in the breeze coming through the large windows. Photo by Motoko Hoshi |

The week before the 2019 Biennale opened, I visited the school and found artists still putting the finishing touches on their presentations. Each had an entire classroom to themselves. Motoko Hoshi appeared nearly done with her installation (though she insisted it was still "in process") and took some time off to explain what it was about and what it meant to her to be working in Nakanojo.

|

|

|

|

|

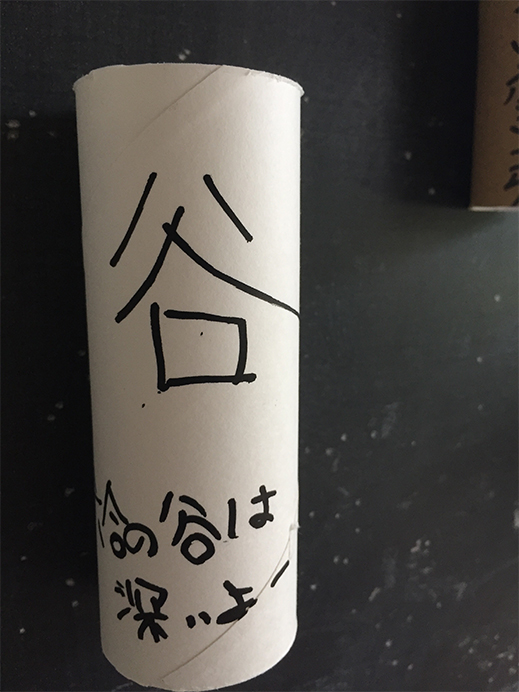

Recycled toilet paper rolls serve as batons on which Nakanojo residents, young and old, have written a kanji character of their choice to describe their hometown. This one, from the village of Kuni, features the character tani (valley) with the comment, "The valley of Kuni is deep!"

|

I had seen Hoshi's work before in Tokyo. Her medium of expression is Kanji, the pictographic characters of Chinese origin that number in the thousands and form the core of written Japanese. Hoshi, a former copywriter, says that she often wondered why languages form such a barrier to mutual understanding, and began experimenting with ways to use written Japanese in a manner that could convey emotions and spiritual messages to people everywhere. She came up with Motokotoba, a word she coined by combining her name with kotoba, meaning word or language. Motokotoba, which she describes as "visual poesy," usually take the form of a square matrix of four Kanji that can be read in any direction, offering a variety of meanings, connotations, and visual associations.

When Hoshi received her commission to create an installation in Nakanojo, she and the other artists were taken on a tour of the festival venues and encouraged to choose where they would like to exhibit. Hoshi found a classroom where children had been taught the Japanese language; above the blackboard across one wall, fraying posters still display the characters of the two Kana syllabaries as models for penmanship practice. "I immediately knew this was where I should do my work," she says.

|

|

Batons bob in the classroom window, drawing the eye to mountan lilies blooming in the schoolyard. This set of four Kanji, chosen in one of Hoshi's grade-school workshops, forms a Motokotoba matrix with the characters yume (dream), tayoru (reliance), yutaka (abundant), and hana (flower). |

In the intervening months Hoshi spent several weeks as an artist-in-residence in Shima Onsen. As she got to know people in the area, she felt a strong desire to create an installation that was theirs as much as hers. The result is the participatory project Create Nakanojo Baton! The titular batons are in fact recycled toilet-paper rolls. On each one, a citizen of Nakanojo -- they range from kindergarten kids to great-grandmothers, though most are grade-schoolers -- has handwritten a Kanji of his or her choice and explained its significance. Hoshi has spent much of her time in the area traveling around to local schools and other facilities to conduct "baton workshops" where she asks participants to think about what living in Nakanojo means to them and write a Kanji that represents their feelings about their community. The response appears to be overwhelming. As I accompanied Hoshi on her rounds that afternoon, we visited several locations where she had installed a handmade "Nakanojo Kanji Collection Box." Each one was full to overflowing with newly inscribed batons. The staff at one office quipped that Hoshi might want to schedule her pickups a bit more frequently.

|

|

Hoshi has organized her batons in compositions inspired, she says, by influences ranging from the surrounding forests to traditional dry-landscape gardens and the tea ceremony. The Kanji on them resonate with the Japanese syllabary lists above the blackboard, left there since the school closed several years ago. The spiral in the foreground continues to expand as visitors add their own contributions. Photo by Motoko Hoshi |

Back at the classroom, Hoshi has crates of these Kanji-inscribed cardboard rolls to work with, and more crates of as yet uninscribed rolls donated by local sources. She has kept her materials minimal, using rubber bands to link the rolls, sausage-like, in springy arrays of every configuration imaginable, from ever-widening spirals to snaky, tubular creatures that crawl across the floor and up the walls like creeping vines. The most visually appealing, at least to my eye, are the many mobile-like strings of batons suspended from the ceiling, which jiggle, twist and turn like silent wind chimes in the breeze coming through the open windows. Interspersed with long slender bamboo poles provided by a local bamboo grove owner, they create a pleasing vertical component, an indoor forest that adds depth and substance to this somewhat ghostly former classroom.

|

|

|

|

|

Motoko Hoshi in her classroom installation at the former Daisan Elementary School in Shima Onsen. |

Hoshi is eager to show how she hopes her constructions will spur the creative impulses of visitors of all ages. Inside a bamboo enclosure that she likens to a Noh stage, a roll dangling in midair may prompt someone to grab it like a microphone and give a speech, or burst into karaoke-style song.

If you can read Kanji it is worth taking the time to read the often poignant messages the people of Nakanojo have written on their contributions to the installation, but even if you can't, the community spirit infusing them is palpable. Hoshi calls these unassuming objects batons because, she says, she envisions the thoughts they express as present-day links between Nakanojo past and future -- especially the latter, dependent as it is on the dreams of the town's youngest citizens. Indeed, Hoshi's baton project is one of the Biennale's more straightforward manifestations of its underlying mission: to help a beautiful but challenged rural community find the means to ensure its survival.

All photos are by Alan Gleason unless otherwise indicated. Artworks are shown by permission of the Nakanojo Biennale, Motoko Hoshi, and Florian Goldmann. |

|

| Nakanojo Biennale 2019 |

| Motoko Hoshi: Create Nakanojo Baton! |

| 24 August - 23 September 2019 |

Nakanojo Town, Gunma Prefecture

Phone: 0279-75-3320 (Biennale Office, Japanese-speaking only)

Hours: 9:30 a.m. to 5 p.m., open every day

Access: Nakanojo Station is on the JR Agatsuma Line, 2 hours northwest of Tokyo. Although there is some bus service between different exhibit areas, visiting by car is recommended.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for over 30 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|