|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Landscapes Without and Within: The Hirayama Ikuo Silk Road Museum

Alan Gleason |

|

A Caravan on the Silk Road (West, Moon), 2005 |

Ikuo Hirayama (1930-2009) is one of the big names of postwar Nihonga. Largely a traditionalist when it came to materials and compositional style, he was at the same time a maverick in his choice of subject matter, which ranged from scenes of desert caravans in Central Asia to the flames that engulfed Hiroshima after the atomic bombing, of which he was a survivor. That traumatic experience at age 15 impacted his subsequent career as an artist in more ways than one. Later in life, however, he enjoyed fame and financial success, garnering numerous accolades and opening two museums in different parts of the country to share his work with the public.

One of these facilities, the Hirayama Ikuo Museum of Art, is located in his hometown of Setoda on Ikuchi Island in the Seto Inland Sea, a bit east of Hiroshima. The other, the Hirayama Ikuo Silk Road Museum, is in a similarly idyllic setting on the slopes of Mt. Yatsugatake in Yamanashi Prefecture, and has the advantage for Tokyo-dwellers of being only two hours by car or express train from the capital. I visited the Silk Road Museum on a pristine November day, with fall colors at their height framing spectacular views of mountains on every side: the Yatsugatake massif, the Southern Alps, and Mt. Fuji soaring over everything in the distance.

Mt. Fuji from Koizumi, 2005 |

As its name suggests, the Silk Road Museum focuses on Hirayama's lifelong affinity for that fabled trade route between China and Europe -- he claimed to have visited different regions along it over 130 times. The museum's centerpiece is a large gallery devoted to the artist's "Great Silk Road Series," eight mural-sized paintings that cover three walls with views of riders on camelback traversing deserts in Western China or Afghanistan, or passing through the ruins of ancient cities in Asia Minor. Hirayama composed the caravan-themed paintings in pairs, showing the same group of riders under the burning orange of the sun by day and, in virtual mirror images, heading in the opposite direction in the cool blue of a moonlit night. He described these pairings as "contrasting versions showing the severity and romance of the desert." Hirayama painted these panoramas not from photographs but from sketches made on location, which he sometimes had to vacate in a hurry due to sandstorms or the risk of attracting bandits. He describes hiring a helicopter to bring him to a spot near the Loulan ruins on the edge of China's Taklamakan Desert, where he sketched a passing group of camel riders in only 40 minutes before a sandstorm forced a hasty retreat.

|

|

The Great Silk Road Series, Gallery 6 |

What drew Hirayama to the Silk Road with such frequency? It was an obsession that he attributes, ultimately, to the atomic bomb. In August 1945 he was mobilized, like many Japanese schoolchildren in the last desperate days of the war, to work on the home front, in his case at an army arsenal in Hiroshima. When the bomb exploded he was in a lumber shed less than four kilometers from the hypocenter, and barely escaped serious injury. After spending the night on a hillside overlooking the fires that engulfed the city, he made his way home to Setoda, where he began to suffer from radiation sickness. Though he survived, he was plagued throughout his life with a low white blood cell count and anemia. The experience later inspired one of his most acclaimed Nihonga, a terrifying sea of orange flame titled The Holocaust at Hiroshima (1978).

Hirayama had already begun drawing in his school days, and was sufficiently talented to get accepted to the Tokyo School of Fine Arts (now Tokyo University of the Arts), where he studied under the Nihonga painter Seison Maeda, later becoming his assistant. However, Hirayama's artistic career was hampered by recurring bouts of illness, and it was his fear of death, he says, that drew him to Buddhism. Inspired by the example of the seventh-century Chinese monk Xuanzang, a legendary figure whose 17-year sojourn to India to receive authentic Buddhist teachings was the basis for the epic novel Journey to the West, Hirayama painted his seminal work Transmission of Buddhism (1959), which combined two themes that would come to dominate his oeuvre: the life of the Buddha, and the Silk Road, which he began visiting in the mid-sixties.

|

|

The Advent of Buddha, 1962 (collection of the Saku Municipal Museum of Modern Art) |

Broadly defining the Silk Road as extending between Rome and Nara, the ancient Japanese capital that preceded Kyoto, Hirayama began to make annual pilgrimages to different sites along the route, painting not only his iconic desert landscapes but also ruins in places as scattered as Ephesus and Palmyra to the west and Loulan and Dunhuang in the east. Two of his most poignant works depict one of the great Buddhas of Bamiyan before and after it was blown up by the Taliban in 2001. Indeed, Hirayama in his later years grew as famous for his efforts to preserve cultural artifacts along the Silk Road as he was for his paintings.

|

|

|

|

|

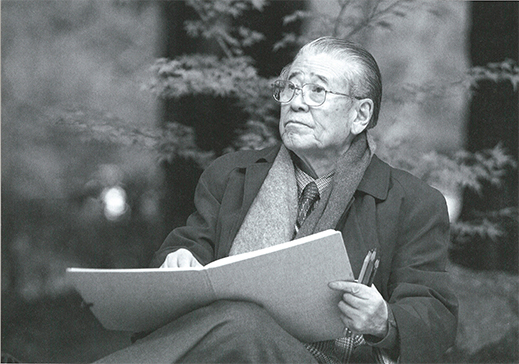

Ikuo Hirayama sketching |

Hirayama's compelling backstory has a way of hampering attempts to critique his artistic endeavors objectively. Not everyone will find his painting style to their tastes. His use of traditional Nihonga pigments is impeccable, but he layers them on with a heavy hand in simple, repeating motifs and colors that are hardly subtle. This is particularly true of his Silk Road works, dominated by orange (day) and blue (night) and populated by caravans whose riders sometimes resemble stenciled copies, like Ogata Korin's celebrated irises. There is some validity to this impression: Hirayama has said that the constraints on his desert visits often gave him just enough time to sketch one of the figures passing by, which he then used as a model for the other members of the caravan.

The Never-Ceasing Stream: On the Upper Reaches of the Oirase River, 1994 |

I found a more nuanced approach to composition and color in his domestic landscapes. One of the most beautiful works on permanent display at the Silk Road Museum is his Cinerama-like wide-screen portrayal of the rushing waters of the Oirase River in northern Japan, with white rapids tumbling around, over and under an array of imposing black boulders and delicate green foliage. Also lovely to look at is his definitive rendering of snowy Mt. Fuji (a Nihonga trope) as seen from a vantage point near the museum. Like the rocks and forest that embrace the Oirase rapids, a foreground of finely wrought winter tree branches balances the dominant white of the mountain. One of the high points of visiting this museum in fair weather is the spectacular view of real-life Fuji that greets you just outside the door.

Cover illustrations for the literary journal Umi (Sea), July 1977 special issue (left) and January 1982 issue (right) |

Another unexpected delight was a gallery of cover illustrations Hirayama drew in the 1970s and 1980s for the literary journal Umi (Sea). Working within limitations of size and deadline, he produced a series of exquisite meditations on motifs ranging from fish to wild grasses to, of course, Mt. Fuji. Just as thrilling is the extensive display of Central Asian Buddhist statuary collected by Hirayama and his wife Michiko, herself a talented artist who accompanied him on most of his Silk Road expeditions and now serves as director of the museum. The Ghandaran Buddhas from Pakistan and Afghanistan offer vivid testimony to the Greek influence on Buddhist sculpture.

Buddhist statuary in Gallery 1 |

All of the above exhibits are worthy reasons to visit the Silk Road Museum, but the beauty of its environs is certainly the capper. Try to go on a day clear enough to afford you some vistas of the surrounding peaks. It's easy to see why Hirayama, who owned a summer villa here, would come to take as much inspiration from the lush landscapes of his homeland as he did from deserts thousands of kilometers to the west.

Exterior view of the Hirayama Ikuo Silk Road Museum in Hokuto, Yamanashi |

All works shown are by Ikuo Hirayama and are in the collection of the Hirayama Ikuo Silk Road Museum except where otherwise noted. All images are courtesy of the Hirayama Ikuo Silk Road Museum.

|

| Hirayama Ikuo: A Retrospective |

| 14 September - 27 December 2019 |

| Hirayama Ikuo Silk Road Museum |

2000-6 Koarama, Nagasaka-cho, Hokuto-shi, Yamanashi

Phone: 0551-32-0225

Hours: 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. (entry until 4:30 p.m.); closed during the winter, from 28 December to mid-March 2020

Access: Next to Kai-Koizumi Station on the JR Koumi Line; one train stop or 10 minutes by taxi from Kobuchizawa Station on the JR Chuo Main Line (2 hours from Tokyo by special express)

|

| Hirayama Ikuo Museum of Art |

200-2 Setoda-cho Sawa, Onomichi-shi, Hiroshima

Phone: 0845-27-3800

Hours: Open year-round, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. (entry until 4:30 p.m.)

Access: 10 minutes' walk from Setoda port, accessed by ferry from Mihara or Onomichi (both stations on the JR Sanyo Shinkansen Line)

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for over 30 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|