|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Restless Omnivore: Hodaka Yoshida at the Mitaka City Gallery

Alan Gleason |

|

Stones and a Man - A (1956), woodblock on paper, collection of the Mitaka City Gallery of Art. |

The life of Hodaka Yoshida (1926-95) is a tale of the happy confluence of talent and circumstance. Yoshida's technical and creative brilliance, manifest first in oil paintings and then, for most of his career, in printmaking, is unquestioned. But he was doubly blessed by being born into a family that provided the optimum environment for pursuing his artistic inclinations, even as the timing of certain events in his life freed him from pressures to adhere to the tight constraints of family tradition.

Hodaka Yoshida: Walls of Wonder, the retrospective currently on view at the Mitaka City Gallery of Art in suburban Tokyo, does a thorough job of introducing us to the diverse periods of Yoshida's oeuvre. One of the fascinating things about his career is that he made several rather abrupt shifts in style and motifs, often inspired by travels abroad that brought him into contact with cultures or art movements whose influences he readily absorbed. But this omnivorous openness owes much to the unique circumstances of his upbringing in a celebrated family of artists.

Hodaka was the second son of two established artists, Hiroshi and Fujio Yoshida. Hiroshi was known for his modernistic revival of the ukiyo-e tradition of woodblock printing in what was known as the shin-hanga ("new print") style. He also encouraged -- to the point of coercion -- his wife Fujio, a talented painter herself and the daughter of Kasaburo Yoshida, another big name in Japanese art (Hiroshi was his adopted son), in her own work. Hiroshi was an equally strict taskmaster with their first son, Toshi, whom he groomed as his successor. Toshi was unable to strike out on his own as an artist until his father died in 1950, and the same might be said for Fujio.

Autumn (1948), oil on canvas, private collection. |

Born 15 years after Toshi, when their father was already 50, Hodaka suffered none of these pressures to follow in Hiroshi's footsteps. Surrounded as he was by all this artistic activity, however, it's not surprising that he began painting on his own -- often late at night in his father's studio when everyone else was asleep. When Hodaka presented his first works in exhibitions -- abstract oils, the polar opposite of Hiroshi's realist prints -- his father dismissed them out of hand. Yet his reaction failed to deter Hodaka, if only because Hiroshi died just a year or two later.

Hodaka was also lucky to begin painting seriously just as World War II ended (he had avoided the draft by enrolling in a college-level science curriculum). Whereas his father and brother had, like all Japanese artists, faced government censorship during the war years, Hodaka launched his career in an era of newly regained freedom, and eagerly took to avant-garde abstraction without a second thought. Just as fortuitously, he met abstract painter Chizuko Inoue in 1949 and married her. Chizuko was already a member of avant-garde artist circles and encouraged Hodaka in that direction.

|

|

Town with Street Stalls (1951), oil on canvas, private collection. |

Autumn (1948), one of the first oils Hodaka exhibited in public, shows that at 22, without any formal training, he was already painting quasi-abstract works that reveal a superb eye for color and composition. A 1951 oil, Town with Street Stalls, attests to his rapid maturation with its assured mix of figurative elements with geometric forms that seem to owe something to Kandinsky and Mondrian. But by 1949 Hodaka was already dabbling in printmaking, and in the early 1950s would leave oil painting entirely behind as he experimented with woodcuts, lithography, and copperplate etching before ultimately settling on the combination of zinc etching and woodblock printing that would become his hallmark.

The transition from painting to printing occurred soon after he met Chizuko, whose avant-garde colleagues were taking the print medium in exciting new directions. Foreign collectors, including officers in the U.S. Occupation Forces, were snapping up traditional ukiyo-e as well as the shin-hanga produced by Hodaka's father, helping legitimize printmaking as an artistic medium in Japan, where it had long been viewed as less respectable than painting. Hodaka himself attributed his new infatuation with printing to a desire to create "un-print-like prints" in a rejection of traditional woodblock art -- his father's world -- as well as to the discovery that "woodblock effects were an almost perfect fit with my hard-edge color plane expressions" (from Mitaka City Gallery curator Satoko Tomita's essay in the exhibition catalogue; English translation by Alfred Birnbaum).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

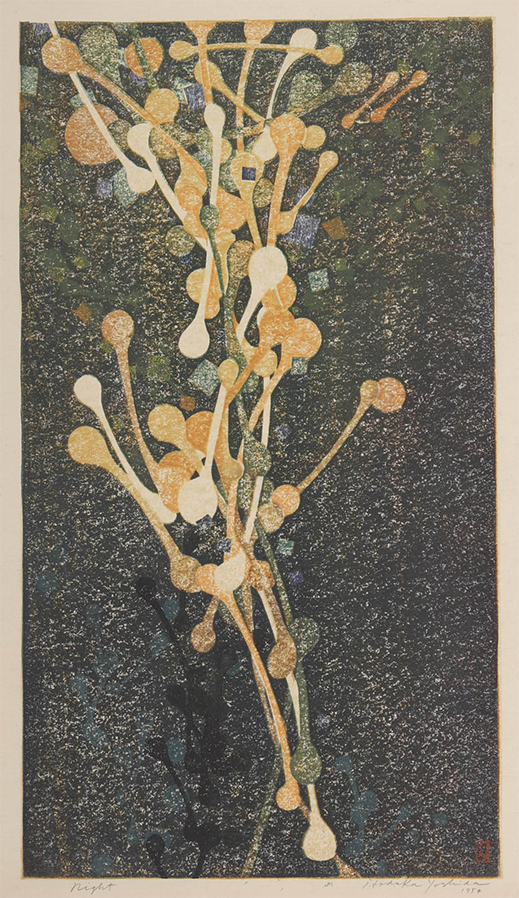

Night (1954), woodblock on paper, private collection.

|

|

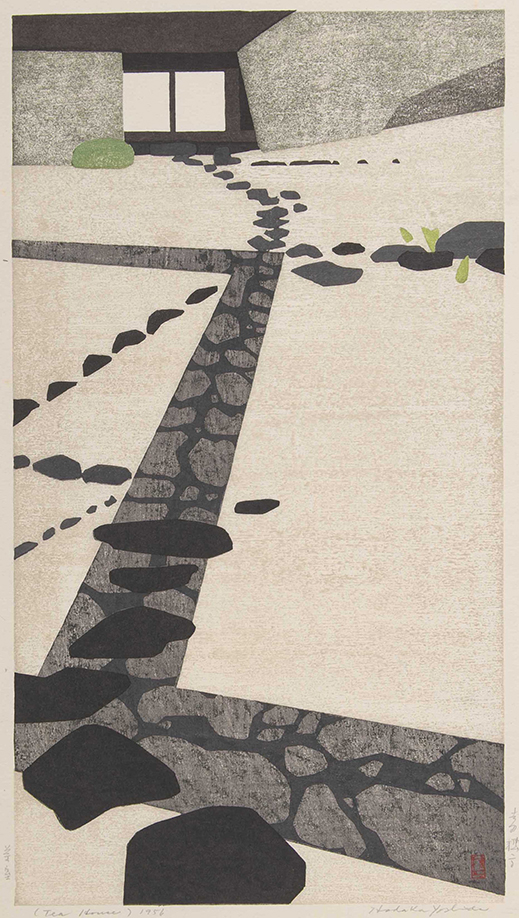

Tea House (1956), woodblock on paper, private collection. |

In his printmaking, Hodaka gave free rein to his impulses toward both abstraction and graphic design, with works ranging from the ambiguous Night (1954) to the more figurative Tea House (1956), from a series inspired by his honeymoon in Kyoto and Nara. But it was a 1955 trip with his brother to the U.S., Cuba, and Mexico that triggered the first really dramatic shift in his thematic material, as is obvious in woodcuts like Stones and a Man - A (1956), composed of circles and other elements inspired by Mayan art.

Another big shift came after Hodaka encountered Pop Art on a visit to New York in 1963. He began to experiment with collage, as in Calendar - Red (1966), producing work in the late 1960s that contained satirical humor and social commentary in colors that leaned toward the psychedelic. Indeed, Hodaka's output during these years resembles that of the legendary graphic designer and painter Tadanori Yokoo, who mined similar influences. (Coincidentally or not, both men later shared a fascination with Y-intersections, the central motif of a series of paintings by Yokoo and Hodaka's own One More Scene, From My Town - Fire Tower (1984).

|

Calendar - Red (1966), woodblock on paper, collection of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.

|

|

One More Scene, From My Town - Fire Tower (1984), zinc etching and woodblock on paper, collection of the Machida City Museum of Graphic Arts. |

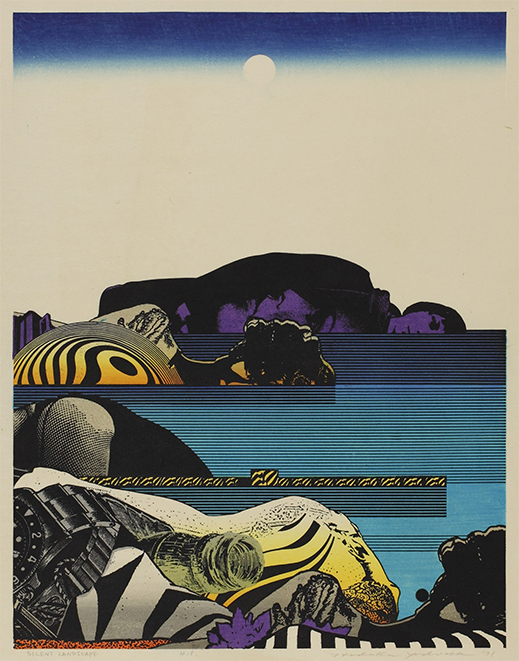

The late 1960s also saw Hodaka trying out alternatives to woodblock, as in a series of very Poppish silkscreens. By the early 1970s, however, he was using the hybrid technique of zinc etching and woodblock that he would stick with for the rest of his life. Around the same time he began to build his works around photographs he had taken on his travels, employing photo-based printmaking techniques inspired by silkscreen art. Hodaka had actually pioneered the use of the process in Japan as far back as 1965, but his efforts first reached fruition in his "Landscape" series from the early 1970s. In Silent Landscape (1971), for example, magazine cutouts form a hallucinatory vision of islands in the sea, but the sun and sky above appear in the exquisite gradations of traditional ukiyo-e.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Silent Landscape (1971), zinc etching and woodblock on paper, collection of the Machida City Museum of Graphic Arts.

|

|

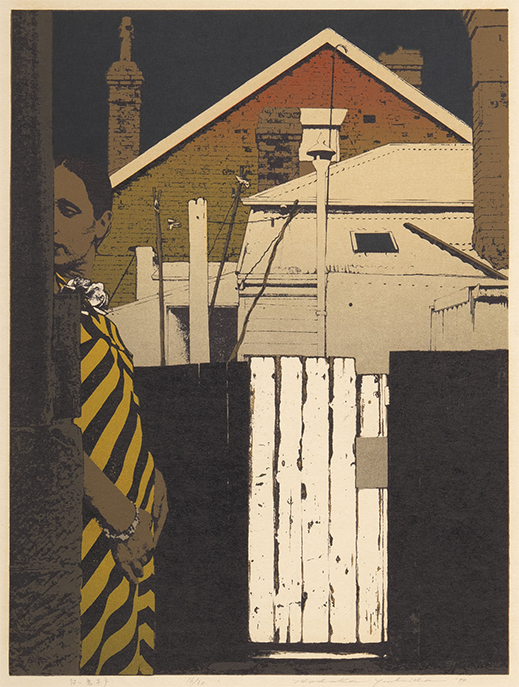

White Back Gate (My Tasmania) (1974), zinc etching and woodblock on paper, private collection. |

Yet another overseas excursion, this one to Tasmania in 1972, provided ample photographic fodder for Hodaka's new approach. For the next six years his output heavily featured cutouts, mostly of women or birds, superimposed on photos of Tasmanian houses. In the 1980s Hodaka focused increasingly on details of old discolored walls and other surfaces in works that border on the abstract. Besides houses and walls, he was fond of wooden pilings, doors, street signs and other random objects he shot in locales both at home and abroad. During his most prolific years, the 1970s and 1980s, he traveled widely and photographed incessantly, usually with three cameras in tow.

Since Hodaka lived with his family in Mitaka from 1967 until his death in 1995, the City Gallery takes a proprietary interest in his work, and has in its possession several of the very large "Wall" prints he produced in his final years. These stunning pieces bring the exhibition to a fitting climax and demonstrate that the artist retained his sublime feel for colors and forms right up to the end. If Hodaka's career teaches us anything, it is that being a sponge of influences -- familial, cultural, environmental -- is no vice in the hands of someone with the skill and sensibility to turn them into art.

|

|

Earth-colored Wall (1992), zinc etching and woodblock on paper, collection of the Mitaka City Gallery of Art. |

The Yoshida family tradition lives on today in Hodaka's daughter Ayomi, a contemporary artist who started out as a woodblock printer but now makes large installations that expand in imaginative ways upon the materials and processes of the woodblock medium. Ayomi Yoshida will be giving a talk at the Mitaka City Gallery on 25 January 2020.

All works by Hodaka Yoshida, images courtesy of the Mitaka City Gallery of Art.

|

| Hodaka Yoshida: Walls of Wonder |

| 7 December 2019 - 16 February 2020 |

| Mitaka City Gallery of Art |

5th floor, Coral Bldg., 3-35-1 Shimo-Renjaku, Mitaka, Tokyo

Phone: 0422-79-0033

Hours: 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. (last entry at 7:30 p.m.)

Closed Mondays (except open 13 January), 29 December to 4 January, and 14 January

Access: Directly across from the south exit of Mitaka Station on the JR Chuo Line (20 minutes west of Shinjuku, Tokyo)

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for over 30 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|