|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries, museums, and other cultural facilities around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

That Was Then: Viewing Tokyo through the Olympic Prism

Alan Gleason |

|

Exterior view of the Machida City Public Museum of Literature (Kotoba Land) |

The city of Machida is in Tokyo, but not of Tokyo. Separated from the rest of the conurbation by the rolling Tama Hills, it has long been a favorite refuge for writers and artists wishing to get out of town but unwilling to move too far away. Such luminaries include Shusaku Endo, author of Silence (made into a motion picture by Martin Scorsese), and Genpei Akasegawa, one of postwar Japan's leading avant-gardists. So it's no surprise that in addition to the usual public libraries, Machida has its own museum dedicated to literature.

Founded in 2006 to house literary materials donated to the city by the estate of long-time resident Endo, who died in 1996, the Machida City Public Museum of Literature began as a decidedly adult-oriented facility. Since then, however, it has made a conscious effort to appeal to young readers as well as old -- hence its kid-friendly alternate name, "Kotoba [Word] Land." The modern brick building looks like a typical municipal library, an impression reinforced when one enters via the ground-floor "Literature Salon," a spacious lobby with an entire wall devoted to an awe-inspiring collection of children's picture books. A reading room in the back offers access to Machida-related books and authors. The space has a warm, informal vibe accented by the brick-tile floor and the presence of a coffee and snack bar in one corner.

The museum entrance and Literature Salon, featuring shelves full of picture books, an Olympics-themed photo display on the wall, and a snack bar with tables |

Upstairs is where the actual museum struts its stuff. A gallery occupying most of the second floor hosts four major exhibitions a year on topics ranging from local literary figures to Japan's publishing and printing culture, with displays running the gamut of genres from fiction and poetry to kiddie lit, manga, films and music. The current exhibition is a bit of a departure from the museum's general emphasis on literature per se in that it examines a particular historical epoch in a particular place. Tokyo Chronicle 1964-2020 is an ambitious attempt to guide the viewer through the changes that buffeted the metropolis in the decades between the Tokyo Olympics of 1964 and those of 2020 (now officially postponed to 2021).

|

|

Masaaki Kasuga, "Rotary in Front of East Exit, Ikebukuro Station" (1964), Hakodate Archives |

There is a trove of information here, much of it visually enticing, that will make any Tokyophile or history buff happy. The show is laid out chronologically and partitioned roughly by decade, leading off with the early to mid-sixties. It starts with a bang -- a wall's worth of black-and-white snapshots of Tokyo before, during, and after the burst of development triggered by the 1964 games. Japan had already entered its high-growth era, but it was the push to turn Tokyo into a symbol of the country's resurrection from the ashes of war -- a triumph for all the world to see -- that spawned a construction boom like no other. The Shinkansen bullet train made its inaugural run; Japan's first skyscrapers sprang up in downtown Tokyo; and a maze of serpentine expressways was hastily extended over the city's Edo-period network of canals (notoriously consigning the historic Nihonbashi bridge to permanent shadow).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Masaaki Kasuga, "In Front of Ginza Matsuzakaya Department Store" (1964), Hakodate Archives

|

|

Tokyo Olympic Torch Holder, designed by Sori Yanagi. Yusaku Kamekura's iconic "TOKYO 1964" posters can be seen on the wall in back. |

Photos celebrating these modern flourishes abound, but the exhibition focuses instead on how Tokyo's older neighborhoods fared amidst the building boom. Photographers like Masaaki Kasuga captured the city in transition, juxtaposing images of crowded alleys with the bare girders of under-construction highways soaring overhead. Telling, too, are the Olympic banners and signs hanging in the storefronts of businesses large and small. It seems everyone was on the Olympic bandwagon -- quite a contrast with the controversies plaguing the 2020/21 games even before the coronavirus made their very feasibility open to doubt. (As we go to press, several candidates in the upcoming Tokyo gubernatorial election are making cancellation of the games a centerpiece of their campaigns.)

|

|

|

|

|

Takeshi Kaiko gets his shoes shined while gathering material for Zubari Tokyo (1964), collection of Kaiko Takeshi Memorial Society

|

Even in 1964, though, a few critical voices could be heard. Journalist Takeshi Kaiko made a name for himself with his anti-Olympic screeds -- notably in Zubari Tokyo (zubari roughly means "no punches pulled"), a book in which he laments the destruction of much of what he loved about Tokyo in the government's haste to make it an international showcase.

True to its literary mandate, the museum gives books and magazines pride of place throughout this show, but alongside the glass cases full of works like Kaiko's it also features a few choice objects sure to thrill Olympics fans of all ages: a genuine Olympic Torch holder, designed by the legendary Sori Yanagi, as well as a set of the prizewinning Olympic posters by Yusaku Kamekura.

Zubari Tokyo (volumes 1 and 2) and other works by Takeshi Kaiko, collection of Kaiko Takeshi Memorial Society |

The second part of the exhibition, covering the late 1960s and early 1970s, chronicles the jarring developments in the years immediately following the 1964 Olympics. Successful though the games were, they merely papered over tensions that were already simmering in society at large. A student movement against the 1960 Japan-U.S. Security Treaty had been quashed not long before. When the Vietnam War began to escalate (the Gulf of Tonkin Incident occurred two months before the opening ceremony), and with it Japan's logistical involvement, campuses exploded with strikes and barricades. This second wave of student activism would also be suppressed by violent police action, but not until the end of the decade. The tumult of the late sixties gave birth to some of the most dramatic photography and sharpest social satire Japan has ever seen, and the curators have put together an impressive selection that makes this section the visual highlight of the show.

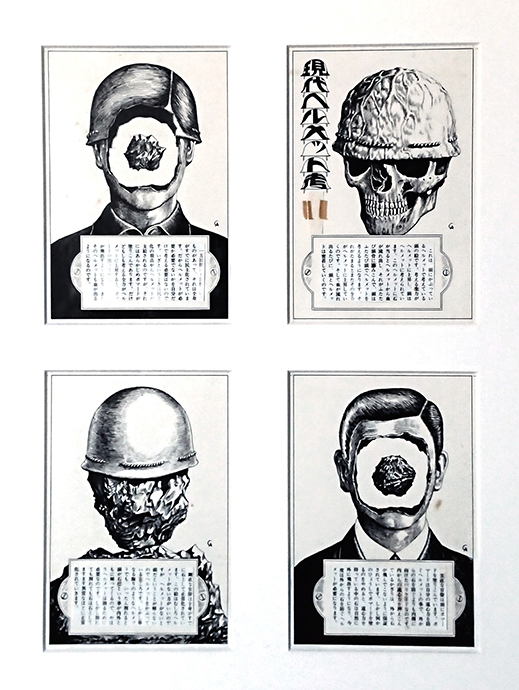

The museum benefits here from its access to the vast oeuvre of one of the era's most prominent satirists, Machida resident and Dadaist artist, author, and cartoonist Genpei Akasegawa (1937-2014). Akasegawa is best known for being arrested, tried, and found guilty of violating Japan's counterfeiting law by printing up fliers with a blurb for an art show on one side and an image of a 1,000-yen bill on the other. His trial morphed into a circus parade of artists and critics who testified that his work was art, not bogus money, though to no avail (he was given a suspended sentence). This episode gets deserved coverage, but more entertaining is an entire corridor lined with the original art for several of Akasegawa's surrealistic manga works. In brilliant juxtaposition, the opposite wall displays a stunning series of monochrome photos taken inside the student barricades at Yasuda Hall on the University of Tokyo campus just before riot police stormed the building in January 1969. Barely out of college herself, Hitomi Watanabe was the only photographer admitted into the hall by the activists. The two sides of this corridor pretty much sum up the sixties in all their contradictions: gonzo flights of the imagination on the one hand, violent confrontation with the powers that be on the other, all at the same time.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Genpei Akasegawa, "On Helmets Today," original (1966)

|

|

Hitomi Watanabe, "Behind the Barricades, Todai Zenkyoto 1968-1969" |

For unremitting drama it's hard to top the sixties, and inevitably the narrative feels a bit anticlimactic as it moves on to subsequent decades. Fortunately the seventies saw a flowering of colorfully subversive, if less overtly political, artistic endeavor. Demoralized by the draconian response to the campus strikes, countercultural artists entered a more introspective phase, one that produced, among other things, the postwar period's finest avant-garde manga. One particular monthly, the celebrated Garo, championed artists like Akasegawa, Yoshiharu Tsuge, Sanpei Shirato, and Shigeru Mizuki who inspired an entire generation of underground art, music, and theater. At this point one begins to suspect that the Kotoba Land curators are partial to the edgier aspects of postwar Japanese culture, or maybe they just know eye-catching graphics when they see them.

The late seventies and eighties were also precisely when Tokyo itself became a subject of interest. The protean satirist and critic Yoshio Kataoka shared his "city observations" in the countercultural magazine WonderLand, soon to be renamed Takarajima ("Treasure Island"). Then the Tokyo Metropolitan Government got into the act, launching Tokyojin ("Tokyoite"), a nonprofit monthly that became wildly popular for its in-depth coverage of Tokyo culture and history, all without intrusive advertising or puff pieces. Now produced by a commercial publisher, the magazine is still going strong; a monument to its longevity occupies one corner of the gallery in the form of a meticulously constructed tower of back issues.

|

|

From the nineties on, the exhibition has a more bookish look, devoting itself to explications of literary trends up to the present. Non-Japanese visitors will recognize such names as Haruki Murakami and Banana Yoshimoto. Though it's not a point made in the texts accompanying the ample book displays, one of the pleasures of an exhibition centered largely around publications is the sheer inventiveness of Japanese cover designs.

With the caveat that it has no English-language signage, Tokyo Chronicle 1964-2020 provides a fascinating and fast-moving look at how literary output and social trends influenced one another in Japan during the half-century bookended by the two Olympics. Though it's too early for us to know how the 2021 games and their impact will be viewed in hindsight (even, or especially, if they never take place), this show offers one intriguing benchmark for comparison in the changes the 1964 games brought to Tokyo, and to Japan as a whole. Originally scheduled to close at the end of June, the exhibition was delayed by Japan's pandemic-related state of emergency but has now reopened and will continue into August. You can see a short video digest of it here.

All images are courtesy of the Machida City Public Museum of Literature (Kotoba Land). |

|

| Tokyo Chronicle 1964-2020 |

| 9 June - 10 August 2020 |

| Machida City Public Museum of Literature (Kotoba Land) |

4-16-17 Haramachida, Machida-shi, Tokyo

Phone: 042-739-3420

Hours: 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesday-Sunday

Closed Mondays and on 9 July 2020 (Thursday)

Access: 8 minutes' walk from the Terminal Exit of Machida Station on the JR Yokohama Line, or 12 minutes' walk from the East Exit of Machida Station on the Odakyu Line

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for over 30 years. Since 2007 he has edited Artscape Japan and written the Here and There column, as well as translating the Picks reviews. He also edits and translates works on Japanese architecture, music, and theater. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|