|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries, museums, and other cultural facilities around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Photo-Realism: Katsumi Sunamori at the Maruki Gallery

Alan Gleason |

|

Kamagasaki, Haginochaya, 1980s |

Katsumi Sunamori (1951-2009) is one of the unsung heroes of contemporary Japanese documentary photography. During his lifetime he was known, if at all, as a hired gun for the weekly scandal sheets. Though he published one prizewinning photo collection, his work was never exhibited in a museum. Now, a decade after his death at 57 from cancer, the show currently up at the Maruki Gallery in Saitama Prefecture offers some 100 of his riveting images of Osaka's skid row, post-bomb tenements in Hiroshima, and Okinawan bar districts, as well as the aftermath of a natural disaster, the eruption of Mount Unzen in Kyushu.

As its full name indicates, the Maruki Gallery for the Hiroshima Panels is home to the world-famous series of murals by Toshi and Iri Maruki depicting victims of the atomic bombing (reviewed some years ago in Here and There). In addition to this permanent display, the gallery also hosts special exhibitions that typically introduce artists expressing a critical perspective on social issues. While Sunamori's subject matter would seem to place him squarely in this category, his point of view is more complicated than a simple urge to confront the inhumanity of humanity. In trying to better understand the impulses behind his work, one has to address his extremely dramatic and fraught backstory.

Exterior view of the Maruki Gallery for the Hiroshima Panels |

Sunamori was born in Okinawa to a Filipino father who worked for the U.S. military and a mother from Amami-Oshima, an island to the north. When he was eight his father left for the Philippines and never came back. When he was fifteen his mother died of illness, and Sunamori traveled to Osaka, where people from the impoverished southern islands often migrated in search of day-labor jobs. Sunamori, however, trained to become a boxer, driven, apparently, by a desire to meet his father again. He adopted his father's name, Saberon, in the ring, and dreamed that fighting in the Philippines one day might lead to their reunion. This was not to be; just before a crucial all-Japan championship match, Sunamori quit boxing and instead enrolled in a photography school in Osaka. With his new skills he found work freelancing for gossip weeklies like Focus and Friday notorious for their shots of celebrities in trouble. Sunamori earned a rep for his ability to sneak into crime scenes and grab lurid close-ups before the authorities shooed him away.

|

|

But he was also pursuing his own photographic muse. On a visit to Hiroshima in 1980, Sunamori was drawn to the ramshackle wooden tenements, built by A-bomb survivors (particularly those of Korean origin, who faced even worse neglect and discrimination than the Japanese victims), that somehow survived in the interstices of the rapidly modernizing city. His stark monochrome portraits of these neighborhoods and their residents were his first systematic scrutiny of the lives of those left behind by the postwar economic boom.

|

|

Returning to Osaka, Sunamori began living in Kamagasaki, the slum where many day laborers from Okinawan congregated and where he had spent time himself. Out of this period emerged a series of stunning color close-ups of people working, drinking, and sleeping on the streets. The lack of self-consciousness displayed by his subjects toward the camera suggests that Sunamori looked and felt like one of them. And yet his images are incisive and devoid of sentimentality: reality seen through a journalist's gimlet eye. Perhaps it's this balance of warm and cool that makes his work so compelling.

During his lifetime, Sunamori's work made a splash in the public eye exactly once, in the form of two photography awards he won in 1996 for his published collection Okinawa Amami Manila (Creo, 1995). Revisiting his birthplace in 1989, he wandered through the tenderloins found outside every U.S. military base in Okinawa, capturing the gaudy dereliction of the island's neo-colonial townscapes. On a trip to Manila, he finally got to meet his father, but the long-sought reunion apparently proved disappointing.

Henoko, Nago City, Okinawa, 1989 |

Kincho, Kunigami-gun, Okinawa, 1989 |

After making one's way through the sections of the exhibition that feature Sunamori's images of Hiroshima, Kamagasaki, and Okinawa, it's easy to conclude that he was a man with a mission, someone whose own hardscrabble life had honed a righteous anger at social and economic injustices that he strove to expose for the world to see. Surely there was some of that in his makeup, but in his own writings Sunamori speaks more of a quest for beauty in images that others might think ugly -- including those of violence, whether by men or by natural forces. In an unpublished text, quoted in an essay by his daughter Kazura, he wrote of boxing:

This is a skill, which if refined becomes a form of "beauty" that flowers in the ring. It remains imprinted in the minds of fans as a beautiful form of "expression." Perhaps the reason I, someone who had no experience at all of fighting, was able to enter the world of boxing without any reservations was because I was under the illusion that if I trained hard enough I could do so. "Beauty" was possible, "expression" was possible. (From Noi Sawaragi, "Notes on Art and Current Events 90," ART iT website; English translation courtesy of ART iT)

|

|

The notion of seeking beauty and expression in brutal circumstances helps explain the content of the fourth series on display here, which documents the devastation wrought by the deadly eruption of the Unzen volcano in Shimabara, Kyushu in 1991. Sunamori visited the area between 1993 and 1995 to find houses still buried in ash and boulders from the pyroclastic flow. As in the Okinawa series, one sees few human subjects; the people who appear here and there are fleeting, ghostlike presences. The focus is on man-made structures that have more than met their match in nature. There is no overt message to be found here about social inequity or human folly (unless it's the folly of living under a volcano). And yet, as gruesome but perversely beautiful reminders of the horror and death that rained down on Shimabara, the images arouse complex emotions.

|

|

|

|

|

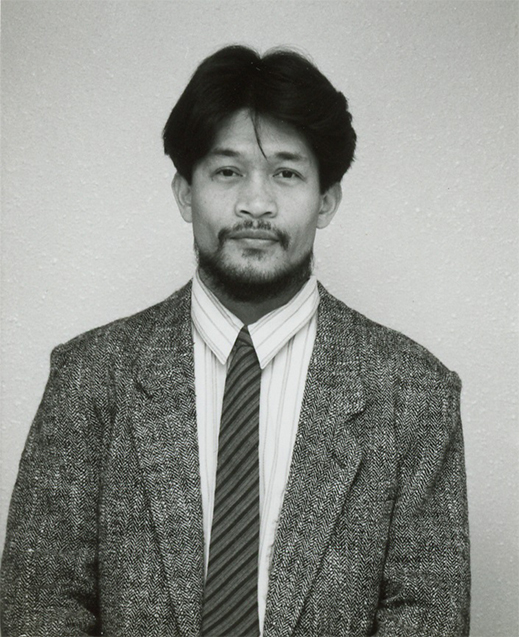

Katsumi Sunamori

|

Sunamori was brought to the attention of the Maruki Gallery by art critic Noi Sawaragi, who became enamored of his work after viewing the Unzen series, and who serves as guest curator of this exhibition. Sawaragi also enlisted the active involvement of Kazura Sunamori, a photographer herself who is dedicated to curating her father's legacy. Complementing the generous selection of prints from the four series is a rapid-fire slide show of Sunamori's extensive and extraordinarily diverse portfolio, in which portraits of Buddhist statuary alternate with snapshots of bar girls with their customers.

The Maruki Gallery is a bit of a trek from downtown Tokyo -- an hour by express train, then a long walk down narrow country lanes (a cab from the station is recommended). However, its pastoral setting above the meandering Toki River is balm for a frazzled city-dweller's soul, particularly in these pandemic days. While there, you do not want to miss the Hiroshima Panels, but expect a searing experience that makes Sunamori's imagery seem soothing by comparison. Afterward, a few minutes sitting on a shady bench overlooking the river will be just what the doctor ordered.

|

|

Students viewing Hiroshima Panel #8, Rescue (1954) at the Maruki Gallery |

All photographs (excluding those of the gallery and the artist) are by Katsumi Sunamori. All images are courtesy of Maruki Gallery for the Hiroshima Panels. |

|

| Katsumi Sunamori: Implications of the Scenery |

| 22 February - 30 August 2020 |

| Maruki Gallery for the Hiroshima Panels |

1401 Shimogarako, Higashi-Matsuyama, Saitama Prefecture

Phone: 0493-22-3266

Open 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. (9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. December - February)

Closed Mondays except national holidays, Tuesdays after national holidays, and 29 December - 3 January. Open every day 1 - 15 August

Transportation: 12 minutes by taxi from Shinrinkoen Station or 30 minutes' walk from Tsukinowa Station on the Tobu Tojo Line (1 hour by rapid express from Ikebukuro, Tokyo)

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for over 30 years. Since 2008 he has edited Artscape Japan and written the Here and There column, as well as translating the Picks reviews. He also edits and translates works on Japanese architecture, music, and theater. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|