|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries, museums, and other cultural facilities around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

His Own Private Minka-en: Sankei Hara's Fabulous Garden

Alan Gleason |

|

The Three-Story Pagoda of Former Tomyoji Temple (1457) soars over the Main Pond in Sankeien Garden. |

Japan boasts plenty of open-air architectural museums, those mini-villages of historical buildings moved from elsewhere. Many go by the moniker of minka-en, literally "folk-house park," and feature authentic thatched-roof farmhouses, rustic tea huts, and hoary temples anywhere from a few decades to over a millennium old. Cities all over Japan have their own locally-sourced minka-en. Rarely, however, has such an assemblage of traditional architecture been the work of one man, and this is what makes Sankeien, a park-sized landscape garden in Yokohama, such a remarkable place.

Filling a valley nestled between two hills in Yokohama's Honmoku district, Sankeien is 175,000 square meters of bucolic splendor. Once inside the gate you are magically shut off from the surrounding city, with nary a high-rise in sight. Instead, what greets you is a vast estate of landscaped gardens dotted with 17 historical structures, ten of which are government-designated Important Cultural Properties. The piece de resistance is a 550-year-old three-story pagoda that looms over the entire garden from its hilltop perch. A public city-run park, Sankeien is open all year -- yes, even this year.

|

|

|

|

|

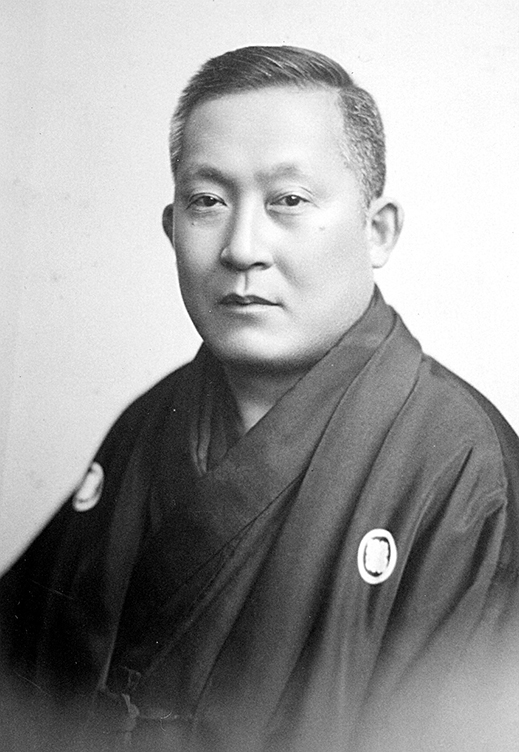

Sankei Hara, year of photograph unknown.

|

The man who made Sankeien is Sankei Hara (1868-1939), the "silk king" of Yokohama, who used the fortune he made from the silk trade in the late 19th century to build his own private Shangri-la. Born Tomitaro Aoki in Gifu, he displayed an interest in the arts and Chinese classics from a young age. When he moved to Tokyo to attend university, he got a job teaching history at a girls' school and ended up marrying one of his students. She happened to be the granddaughter of Zenzaburo Hara, a wealthy Yokohama silk merchant, and Tomitaro was adopted into the family and put in charge of its business. He quickly became one of Japan's top silk exporters at a time when Western demand for Japanese silk was at an all-time high. He also built and bought weaving mills, among them the Tomioka Silk Mill, Japan's first modern silk reeling factory and a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Meanwhile his grandfather-in-law had purchased an entire valley, Sannotani ("Third Valley"), which opened out onto Tokyo Bay a few miles south of Yokohama harbor. Zenzaburo built a summer house atop a cliff overlooking the bay, but the rest of the property, mostly marshland and rice paddies, remained unused. When Zenzaburo died in 1899, Tomitaro, by now a wealthy man in his own right, embarked on an ambitious project: converting the entire Sannotani property into a traditional Japanese stroll garden centered around a large pond. Two gardens, actually: half of the site would be a public park, his gift to the citizens of Yokohama, while the other half would be his family's private estate.

|

|

The front gate of Sankeien, photographed around 1906. Straight ahead is the Kakushokaku, the residence of the Hara family. |

At some point Tomitaro began using the penname Sankei, an alternate rendering of Sannotani, and named his new playground accordingly. The first structure Sankei built at Sankeien was a residence for his family. Completed in 1902, the Kakushokaku covered 950 square meters and was the first building one saw upon passing through the gates to the park. Enamored, perhaps, of the notion of country living, or inspired by memories of rural Gifu, Sankei designed it himself in a style that was part farmhouse, part sukiya-zukuri, the type of residence favored by early Edo-period (1603-1867) nobility.

The Kakushokaku viewed from the public-access Outer Garden, photographed between 1920 and 1930. |

Sankei also designed the overall garden, replete with two artificial creeks through which water cascaded down from opposite hillsides into the pond. Records say that he hired 300 gardeners to do the job. He also began populating both the public Outer Garden and private Inner Garden with sublime examples of classical architecture transported from Kyoto, Kamakura and elsewhere, augmented by other traditional-looking structures he built from scratch. After moving his family into the Kakushokaku and opening the Outer Garden to the public in 1906 he continued to add to his collection, acquiring a dozen historical buildings for the garden over the next two decades.

View of the Inner Garden, with the Rinshunkaku at right, the Teisha Bridge at left, and the Choshukaku at center rear. |

Several of Sankei's purchases were from impoverished or abandoned Buddhist temples in Kyoto and Kamakura. The Meiji-era (1868-1912) government's anti-Buddhism campaign (while it promoted Shinto as the state religion) had resulted in the destruction of many temples, while others remained in desperate straits and were only too happy to sell their assets to someone willing to cart them away and preserve them. From the abandoned Tomyoji temple in Kyoto, Sankei acquired his centerpiece, a three-story pagoda, and reassembled it on the highest hill on the property, near Zenzaburo's clifftop villa. Built in 1457, it is the oldest structure in Sankeien and the oldest wooden pagoda in the Kanto region.

The Rinshunkaku (1649) has been likened to the Katsura Imperial Villa in Kyoto, which was built only a few years earlier. |

The Inner Garden in particular boasts a number of buildings associated with the Tokugawa family of Edo-period shoguns. The Rinshunkaku is a spacious villa built in Wakayama in 1649 by Yorinobu, son of the first shogun Ieyasu. Its austere, stately design has been compared to that of Kyoto's fabled Katsura Imperial Villa, inspiring some scholars to dub Sankeien the "Katsura of the East." The smaller Choshukaku is a two-story pavilion of unique design built in 1623 on the premises of Kyoto's Nijo Castle for the third shogun, Iemitsu. It was Sankei's final acquisition, in 1922. He placed it in a prime spot at the top of the Inner Garden, from where it looks out across Sankeien to the pagoda on the far hill. Surrounded by maples, it's one of the most exquisite places anywhere to enjoy autumn foliage.

The quaint Choshukaku pavilion (1623) sits by a stream in the upper corner of the Inner Garden, seen here at the height of autumn. |

An aficionado of the tea ceremony, Sankei installed or built several tea houses around the property, designing two of them himself. He was also a patron of the arts, and not only amassed an impressive collection of old paintings, but actively supported young Nihonga painters like Taikan Yokoyama and Kanzan Shimomura, who spent time as artists-in-residence at the Kakushokaku. He also hosted luminaries from overseas, notably the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore, who stayed for two months at the Shofukaku, the original Hara family villa overlooking the sea.

Sankei died in 1939, just before the outbreak of World War II. The garden was subsequently requisitioned by the Japanese Army, suffered severe damage in the Allied firebombings of Yokohama, then was requisitioned again by U.S. Occupation forces. Though the Hara family continued to live at the Kakushokaku after the war, they lacked the wherewithal to repair the garden. In 1953 the family donated the entire estate to the city of Yokohama while retaining ownership of the residence (though they no longer lived there). The city created the Sankeien Hoshokai Foundation, which oversaw the full-scale restoration of the garden and its buildings. When this was completed in 1958, Sankeien was reopened to the public. Around this time the foundation also purchased the Kakushokaku from the Hara family.

|

|

|

|

|

View into the interior of the Choshukaku. Photo by Alan Gleason

|

Since then, the foundation has continued adding to the trove of valuable old buildings in the Outer Garden. Notable acquisitions include the Former Yanohara Family Residence, a beautifully restored example of the gassho-zukuri style of farmhouse associated with the Shirakawa-go district of northern Gifu Prefecture, where it originally stood. Moved to Sankeien in 1960, it's the only historical structure in the garden whose interior is open to the public year-round. Another significant acquisition, in 1987, was the Main Hall of the Former Tomyoji Temple, built in 1457, the same year as the pagoda from the same temple.

The former Hara residence, Kakushokaku, had meanwhile been allowed to deteriorate and some thought was given to tearing it down. However, a survey indicated that it was still structurally sound, and in 2000 it reopened after extensive renovations restored the mansion to its original 1902 grandeur, complete with a 40-tatami-mat hall where Sankei entertained guests, and a magnificent expanse of thatched roof. It is now operated by the city as a rentable venue for weddings, tea gatherings and other events. Another significant addition to the park is the Sankei Memorial, a multipurpose building of traditional design that houses the park office, exhibits on Sankeien's history and Sankei's art collection, a tea room, and a gift shop.

|

|

|

|

|

Oil refineries, tankers, and an expressway make for an unnerving spectacle stretching beyond the cliff where the Hara summer home once stood. Photo by Alan Gleason

|

Today Sankeien is in better shape than ever. Among the largest and most historically interesting of Japan's many formal gardens, it's a veritable minka-en Disneyland for traditional Japanese architecture buffs and a sanctuary from the woes of the world for any visitor. The illusion of pastoral isolation is so compelling, in fact, that it's a jarring experience to climb the hill behind the pagoda, then look down the other side at the dystopian panorama just below. This is the legacy of Japan's development spree in the 1960s, when the Honmoku shoreline was reclaimed right up to the foot of the cliff and covered with a tangle of expressways, oil tanks and loading docks. One look is enough to send one scampering back downhill to the comforting oasis of Sankeien. For those of us in need of a little spiritual succor in these trying times, there's no nicer place to find it than this patch of paradise in the midst of the Tokyo-Yokohama conurbation.

All photos are courtesy or by permission of the Sankeien Hoshokai Foundation. |

|

| Sankeien Garden |

58-1 Honmoku-Sannotani, Naka-ku, Yokohama, Kanagawa

Phone: 045-621-0634

Hours: 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily (last entry at 4:30 p.m.)

Access: 5 minutes' walk from the Sankeien-Iriguchi bus stop, 15 minutes on City Bus No. 8 or 148 from Exit 4 of Motomachi-Chukagai Station on the Minatomirai Subway Line. There is also automobile parking.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for over 30 years. Since 2006 he has edited artscape Japan and written the Here and There column, as well as translating the Picks reviews. He also edits and translates works on Japanese architecture, music, and theater. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|