|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries, museums, and other cultural facilities around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Naoto Ogura: Painting as Meditation

Alan Gleason |

|

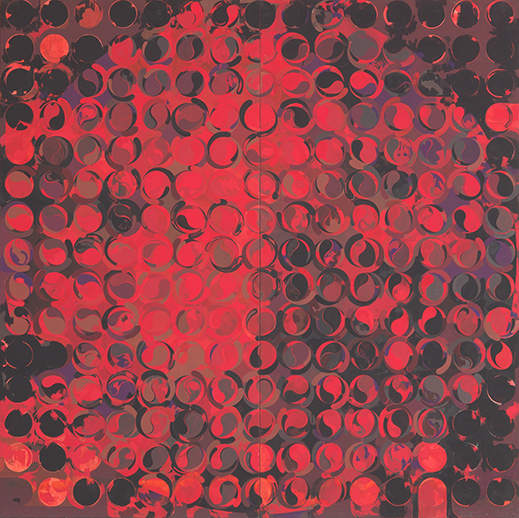

Mandalas of the Two Realms: Womb Mandala 3 (1980-84), mineral pigment and acrylic on paper, 182 x 183 cm; Gan'okuji temple |

Naoto Ogura (1944-2009) won fame in his mid-thirties for a series of mandala paintings that were radically abstract. Then he spent the rest of his life shunning the spotlight and turning out orthodox portraits of bodhisattvas, arhats, and other holy figures in the Buddhist pantheon. However jarring, that shift makes sense when we examine his life, which was consumed by a dogged quest for some sort of spiritual truth. Prayers and Space, an exhibition at the Tokyo and Osaka branches of the Takashimaya Department Store, provides ample opportunity for such an examination.

Born in Manchuria at the very end of World War II, Ogura was repatriated to Japan with his family only a year later. They settled in Minamisoma, Fukushima, where his maternal grandparents lived, but later moved to Kawasaki, just south of Tokyo. Ogura evidently showed artistic talent early on, because he was admitted to the prestigious Tokyo National University of Fine Arts (Geidai). However, the first indication we have of a budding concern with the inner life is when he moved from a university dormitory to one run by a Zen Buddhist temple in the Tokyo suburb of Kichijoji. His writings from this time express a determination to devote himself to painting "come what may," suggesting the conflation of the artist's quest for personal truth with a religious pilgrim's search for enlightenment. For the rest of his life Ogura would speak of painting as merely a means to the end of grasping an inner truth.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Itsukaichi (1977), oil on canvas, 73 x 61 cm; private collection

|

|

Zelkova Tree on the Itsukaichi Road (1977), mineral pigment on paper, 32 x 41 cm; private collection |

Leading a rather nomadic life after graduation as he pursued his art while surviving on teaching jobs, Ogura drew the occasional Buddhist figure, but his most noteworthy works during his twenties were semi-abstract landscapes and still lifes that show the influence of Cezanne and Van Gogh. Many depict the bucolic Itsukaichi valley in the hills west of Tokyo, which Ogura frequently visited. At age 29, however, a near-fatal bout of hepatitis transformed his art and his life. He would write later of how this brush with death made him feel that he was on borrowed time for the remainder of his days. Upon release from the hospital he moved to the mountains of central Japan, worked on a farm until he had recovered his health, then returned to the Tokyo suburbs and began painting mandalas.

Ogura's mandalas are anything but conventional renderings of the Buddha-realms. Highly abstract works, they only obliquely reference traditional Japanese mandalas through their iterations of circles and squares. These are overlaid with interlocking patterns of curving lines that resemble jigsaw puzzles, or sometimes the clouds in Yamato-e screen paintings -- nary a Buddha in sight. Painted with acrylics as well as Nihonga-style mineral pigments, the mandalas run the tonal and emotional gamut from fiery reds and yellows to chilly blues to dark, dour grays and blacks. For about six years Ogura appears to have worked like a man possessed on the series for which he remains best known. Mandalas of the Two Realms is actually two sets of nine paintings, each set arranged in a square matrix respectively representing the Diamond Realm (Kongokai) and the Womb Realm (Taizokai) of esoteric Buddhist philosophy. The former realm is a manifestation of the cosmic, unchanging Buddha-principle, while the latter portrays the living Buddha in the physical world. Mandalas of the two realms are typically populated by hundreds of Buddhas, bodhisattvas and other deities.

|

|

Mandalas of the Two Realms: Womb Mandala 2 (1980-84), mineral pigment and acrylic on paper, 182 x 183 cm; Gan'okuji temple |

Ogura began his first series, the Diamond Realm, in 1976, when he was 32, and embarked on the Womb Realm in 1980. In all he painted 18 mandala squares, each one a canvas measuring nearly two meters on a side. When the first series had its debut at a Ginza gallery in 1978, it made the Tokyo papers. For the next six years Ogura's mandalas would appear in many venues, yet it seems this sudden popularity did not sit well with him. When he completed the second series in 1984, at age 40, he stopped holding solo exhibitions altogether. Meanwhile, he had already produced a number of very traditional paintings of Buddhist deities. In 1987 he painted his last mandalas, a group of monochromatic works that retained the nine-square matrix format but filled it with numbers -- inspired, he said, by Jasper Johns.

|

|

|

|

|

Thirty-three Forms of Kannon, 31: Funi Kannon (1990-96), scroll, 95 x 48 cm; Gan'okuji temple

|

From then on, Ogura only painted Buddhist figures with Nihonga pigments on paper, in a style so faithful to convention that he received commissions from temples as well as private collectors. Yet his primary motivation was not economic. As he wrote, painting these icon-like images was an act "not of creation, but of discipline." It was his form of meditation. He shipped most of the paintings to Gan'okuji, a Zen temple in his childhood home of Minamisoma, to which he donated all of his giant mandalas as well. Except while on loan, they remain there today.

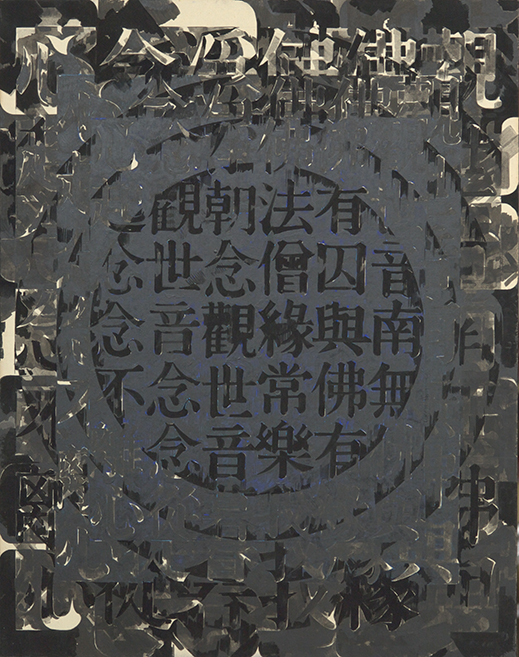

During this period Ogura was fond of painting series of deities and saints in groupings found in the Buddhist pantheon, such as the 33 manifestations of the bodhisattva Kannon, and the 16 arhats, enlightened disciples of the Buddha. Only rarely did he revisit the abstract style of his mandalas, but when he did it was to sublime effect, as in a muted gray-and-black acrylic work on paper from 1998, The Life-Extending Ten-Line Kannon Sutra, which frames the text of the sutra in a circle. Occasionally he produced more ambitious tableaux on Buddhist themes, notably his takes on a favorite scene, the gathering of grieving beings -- animals as well as disciples -- to pay their respects to the historical Buddha, Sakyamuni, on his deathbed as he enters Nirvana. In one such work Ogura reveals a playful side, adding a pair of pandas to the usual assembly of birds, monkeys, tigers and deer.

|

|

The Life-Extending Ten-Line Kannon Sutra (1998), acrylic on paper, 42 x 53 cm; Gan'okuji temple |

At age 58, not long after painting the Nirvana scene with the pandas, Ogura took his monastic inclinations a step further, cutting off ties with the art world and even his friends, and dedicating himself more exclusively, if that were possible, to painting Buddhist figures. (If you have by now acquired an image of Ogura as a complete recluse, it may come as a surprise to learn that he was happily married; his wife contributed a moving memoir to the exhibition.) Perhaps his withdrawal from the world was based on a premonition, because at age 64 his health took a sudden turn for the worse. Reluctantly entering a hospital for the first time in over three decades, he mused that his survival since his previous illness had been a "gift," which he felt he had put to fairly good use. He died at home a month later, in January 2009.

During the final years of his life, Ogura's interests turned in a new direction, to sansuiga, the "mountain and water" ink-brush paintings inspired by Chinese classicists. This was a medium, he declared, that helped him focus on the "inner self" like no other. Sadly, he completed only a few sansuiga before his health gave out. However, the exhibition ends on a note of redemption and hope with a 1995 painting, The Holy Bodhisattva Kannon, that barely escaped destruction when the tsunami of March 11, 2011 inundated the city of Ishinomaki. The water line can be seen at the bottom of the picture, just below Kannon's feet.

|

|

|

|

|

The Holy Bodhisattva Kannon (1995), color on paper; damaged in 2011 tsunami; private collection

|

Prayers and Space (which recently ended at Takashimaya's flagship Nihombashi store in Tokyo, but is currently on exhibit at its Osaka store) offers a solid overview of the intriguing trajectory of Ogura's life and career, as well as copious quotations by the artist that often sound like Zen riddles -- more's the pity for non-Japanese visitors that they are not translated into English. But the works on display do not really need explanation, and the mandalas are without exception stunning. The massive Diamond Realm and Womb Realm paintings dominate, of course, with all but two of the original 18 on view. One can't help wishing they could be seen in their full matric array, but that would require a six-meter-high wall to mount them on.

Though the show does not ultimately illuminate just what made Ogura tick, the sincerity and single-mindedness of his pursuit of spiritual attainment on his own terms, not to mention his abrupt dismissal of worldly success, offer a refreshing antithesis to the environment of relentless but ephemeral stimuli in which we immerse ourselves today. The introspective, reflective nature of his life and work resonates at a time when it increasingly feels as if second thoughts may turn out to be the best ones.

|

|

The Nirvana of Sakyamuni Buddha (2000), color on paper, 104 x 96 cm; Gan'okuji temple |

All images courtesy of NHK Promotions. |

|

| Naoto Ogura: Prayers and Space (in Japanese only) |

| 24 March - 12 April 2021 |

| Osaka Takashimaya 7F Grand Hall |

5-1-5 Namba, Chuo-ku, Osaka

Phone: 06-6631-1101

Hours: 10 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. daily; to 4:30 p.m. on 12 April

Access: Direct access from Namba Station on the Midosuji, Yotsubashi and Sennichimae Subway Lines and the Nankai Line; from Osaka Namba Station on the Hanshin and Kintetsu Lines

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for over 30 years. Since 2006 he has edited artscape Japan and written the Here and There column, as well as translating the Picks reviews. He also edits and translates works on Japanese architecture, music, and theater. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|