|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries, museums, and other cultural facilities around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Clumsy Genius? Yosa Buson at the Fuchu Art Museum

Alan Gleason |

|

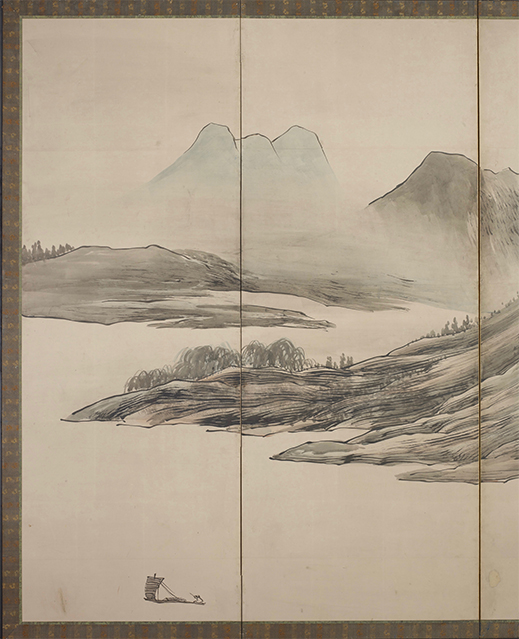

Two panels from a pair of six-panel screens, Folding Screens Pasted with Pictures of Landscapes, Flowers, Birds, and People, c. 1754-57, ink on paper, private collection. The figure resembles one of the hermits or wandering scholars who frequent the Chinese paintings Buson admired. The light touch of the brush is typical of his Tango period. |

Among the Big Three haiku poets of Japan, Yosa Buson (1716-84) tends to lag in name recognition behind Matsuo Basho and Kobayashi Issa. Basho is the undisputed top dog of the genre and author of the immortal travelogue Oku no hosomichi (Narrow Road to the Deep North), while Issa is the rustic, impoverished eccentric with the tragic life and mordant wit. Buson's verse may be just as brilliant as that of his rivals, but his backstory is not quite as compelling. However, he does have an extra claim to fame: before he began to win posthumous acclaim for his poetry, he was celebrated as a painter. A recent exhibition at the Fuchu Art Museum featured more than 100 of Buson's visual works, demonstrating just how remarkable a feat this multitasking was -- particularly as he came to painting somewhat later in life.

Buson was born into a well-off family in what is now Osaka, but moved at age 20 to Edo to study poetry with the master Hayano Hajin and immerse himself in the work of Basho, who had died four decades earlier, in 1694. When Hajin died, Buson took the tonsure as a Buddhist monk and promptly embarked on a trek through northern Honshu, following the course Basho chronicled in Oku no hosomichi and publishing a record of his own journey. Buson moved around a lot before settling in Kyoto at age 42, where he resumed civilian life, married, and raised a family. For several years before that, however, he lived in Tango, a rural province northwest of Kyoto, where he honed his painting skills, mostly on his own. In Kyoto he wrote and taught poetry and gradually made a name for himself as a painter. Apparently he was able to eke out a living doing what he loved, and survived to the relatively ripe age of 68.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Four panels from a pair of six-panel screens, Folding Screens with Landscapes, c. 1754-57, ink on paper, private collection. Choso, the name Buson signed these with, was one he used while in Tango. |

Though highly regarded in his lifetime for accomplishments in both art forms, Buson has never quite enjoyed the adulation afforded peers who dedicated themselves to one or the other medium. Still, getting props as one of haiku's Big Three ain't bad. As for his painting, the Fuchu exhibition's title riffs off of the ambivalence some critics feel about his artistic prowess even today.

Titled Yosa Buson: An Artist Who Turned "Clumsy" into Art, the show takes as its hook not the poet-cum-artist angle, but what curator Nobuhisa Kaneko calls the "clumsy" aspects of Buson's art. The Japanese word is gikochinai, meaning inept, awkward, labored. Kaneko's thesis is that a chronological examination of Buson's paintings reveals an interesting development. His early work, particularly from his Tango years, does indeed have a somewhat amateurish quality. His human faces look a little off-kilter, often with quizzical expressions that may or may not be intentional. In his sumi-ink landscapes, the mountains sometimes resemble mounds of striped ice cream on the verge of meltdown. Though undeniably charming, you'd have to admit there's an endearing sort of Grandma Moses quality to his efforts. Kaneko goes so far as to liken them to the heta-uma "bad-good" style of deliberately funky contemporary manga.

|

|

|

|

|

|

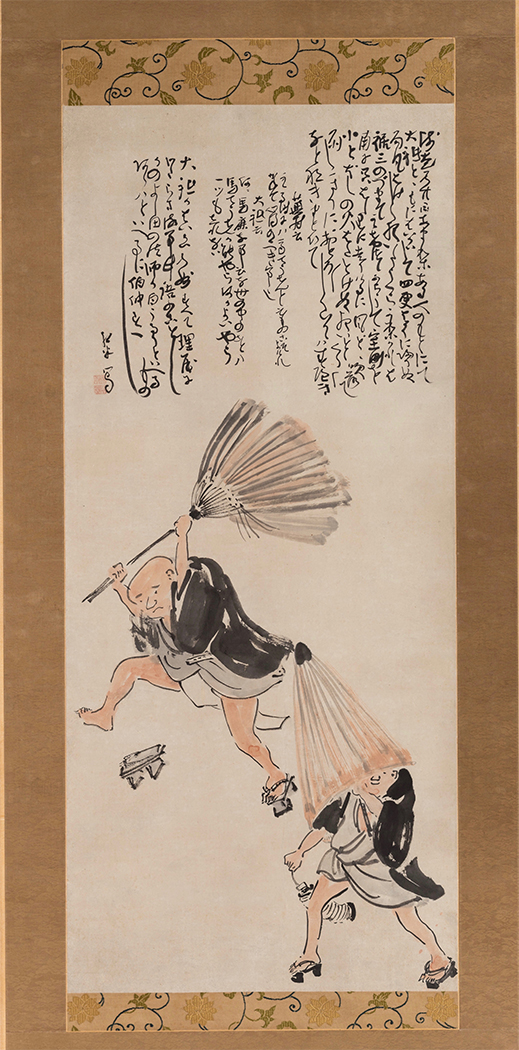

Hanshan and Shide, 1758, ink on silk, private collection. These two Tang-era Chinese sages frequently appear in Zen paintings. The poet Hanshan lived alone on a mountain but would often visit his friend Shide (with broom), who worked in a temple kitchen. Painted the year after Buson moved to Kyoto from Tango, this is the earliest known of many portraits he would make of the two characters.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Taigi and Buson in a Storm, 18th century, ink on paper, collection of Aizu Museum, Waseda University. Buson's text tells a humorous tale of how he and his poet friend Tan Taigi (on the left) were caught in a rainstorm on their way home from a haiku gathering in Kyoto.

|

|

|

|

|

|

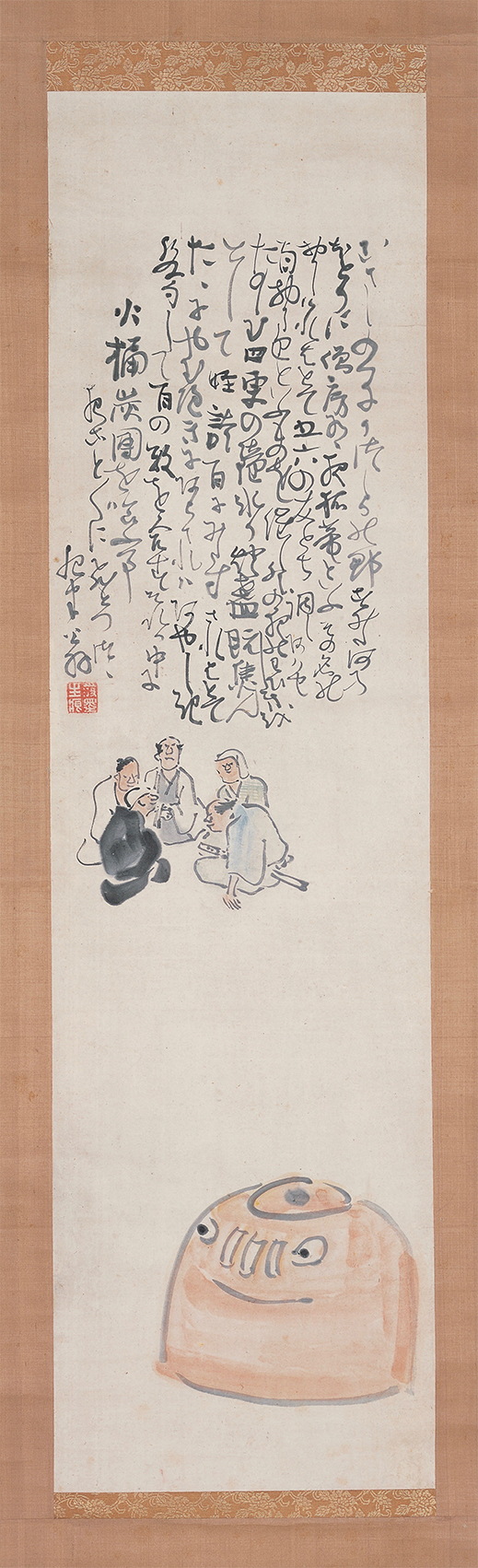

Charcoal for the Brazier, 18th century, ink on paper, collection of Torek Museum of Art. Buson's text describes a storytelling session where someone makes up a ghost story about a charcoal-eating brazier; the grin on the brazier in the foreground suggests the tale is about to come true.

|

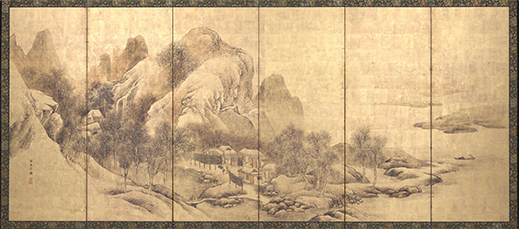

After Buson settled down in Kyoto, though, his technique steadily improved. The landscapes he painted in his last years are masterful in execution -- so much so that one kind of misses the quirky charm of his early work. On the other hand, Buson's portraits just keep getting quirkier. His brushwork is quicker, more fluid, but the facial expressions and body language of his subjects retain all their idiosyncrasies. It becomes clear that Buson's eye for human weirdness is sharp as a tack, and always was. What we might have mistaken for clumsiness in his early sketches appears, in hindsight, to have been playfulness all along.

Part of that "clumsiness" may have to do with Buson's fascination with the Tang- and Song-era literati of China's "southern school" and his desire to emulate their versatility as both poets and painters. His early sumi-ink landscapes are closely modeled on the traditions of the continent, and it is not until much later that he matures into a style that could be called his own. The vast multiscreen landscapes on view at Fuchu are beautiful, but follow the usual tropes of tiny bridges, hermit huts, and human figures dwarfed by towering cliffs that recede into the mist. It's his portraits of people from all walks of life that reveal Buson's whimsical bent as well as his skill at caricature. Many of his works combine sketches and handwritten texts -- proto-manga, if you will, and often gag-driven. One such piece tells of a ghost story that threatens to come to life, while another relates the misadventures of Buson and a fellow poet as they make a tipsy attempt to find their way home in a storm. One doesn't have to read the text to enjoy the humor in the drawings.

This beguiling mix of august landscapes and chuckle-inducing portraits makes a good case for Buson's painterly reputation, demonstrably undercutting -- as is the Fuchu show's intention -- the conventional wisdom that as an artist he was a late bloomer who only reached his stride toward the end of his life.

furu gosho ya

mushi ga tobitsuku

kinbyobu

in the old palace

a bug sticks

to a gold-leafed screen

The Fuchu show is over, alas, having closed prematurely due to the latest pandemic-related quasi-lockdown in Tokyo and other hard-hit prefectures. I was lucky to make it there on what turned out to be its final day. The museum was thronged with Buson fans, and the staff were beside themselves trying to deal with the sudden influx while preparing to shut down on such short notice. But they graciously took the time to meet with me and send the images of Buson's work that you see here.

|

|

|

|

Folding Screens with Landscapes, a pair of six-panel gold-leafed screens, right (above) and left (below), 18th century, private collection. A late-period work, this sublime panorama testifies to Buson's mastery of the Chinese literary-school style of landscape painting. It is also interesting to compare with his earlier Tango-era landscapes. |

|

|

|

|

|

Summer Valley, Visiting a Friend, 1771, colored ink on paper, private collection. The hermit in his hut does not appear to be expecting company.

|

Opened in 2000 in Fuchu no Mori, a large suburban park some miles west of central Tokyo, the Fuchu Art Museum holds its own against the better-known museums downtown. Blessed with extensive floor space and perhaps an enlightened city budget, it supports more than its share of worth-see exhibitions. The Buson show was no exception and its sudden closure was all the more regrettable, as is the fact that it's not scheduled to travel to other venues.

However, the next exhibition at Fuchu looks equally promising. Picturesque Japan is an attractive selection of paintings and woodcuts from the museum's collection that portray the many scenic spots for which Japan is noted. These landscapes and cityscapes, which depict the country as artists saw it during the decades from the late Edo period (1603-1867) well into the Showa era (1926-89), offer scenery-starved Tokyo-area residents some welcome visual respite from the monotony of pandemic life. Though delayed by the extension of the emergency declaration in greater Tokyo, as of this writing the show is slated to open when the emergency is lifted on 1 June.

All images are courtesy of the Fuchu Art Museum. |

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for over 30 years. Since 2006 he has edited artscape Japan and written the Here and There column, as well as translating the Picks reviews. He also edits and translates works on Japanese architecture, music, and theater. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|