|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries, museums, and other cultural facilities around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A Pop-Surrealist for the Ages: Tiger Tateishi at the Chiba City Museum of Art

Alan Gleason |

|

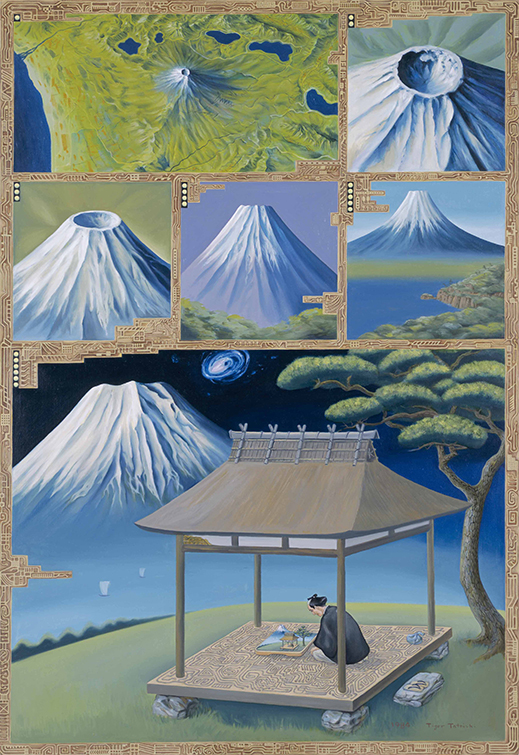

DNA of Fuji (1992), with a self-portrait of the artist, oil on canvas, courtesy of Anomaly. |

"I don't want to be a painter, or an illustrator, or a cartoonist. What I want is unremitting anarchy." This quote pretty much sums up Tiger Tateishi's philosophy of art and life. The dizzying variety of media he put his hand to, and the fluidity with which he moved between them, suggest someone whose self-identity as a free spirit prevented him from clinging to any one way of expressing himself. The current Tateishi retrospective at the Chiba City Museum of Art is an exhaustive but never tedious trek through a career that overwhelms the beholder with the sheer force and volume of its creative output. In the bargain one gets a thorough lesson in postwar Japanese history, because Tateishi was nothing if not a willing channel for the times he lived in.

Born Koichi Tateishi in December 1941, days after Pearl Harbor (as he was fond of noting), he was raised in less than auspicious circumstances in a coal-mining town in Kyushu. His earliest memories were of two U.S. air raids on the mine where his father worked. Peace initially brought only more deprivation, but young Koichi found an escape in manga and Disney films, and was soon drawing on his own. Ridiculously precocious, he won his first art prize at age six and had his work published in a manga weekly at 13. As soon as he finished high school he headed for Tokyo, where he entered art college but soon fell in with the Dadaist avant-garde of the early sixties.

Community (1963/1993), mixed media (oil, driftwood, tin plates, plastic, etc. on six wood panels), Aomori Museum of Art. |

Roughly chronological, the Chiba show begins with an oil painting by the artist as a 16-year-old. A landscape of a mountain near his home, it's a fair imitation of Cezanne in a style he quickly abandoned once he got to Tokyo. He made his first public splash at the Yomiuri Independent show in 1963 with Community, a huge display of parallel panels covered with artifacts: arrays of such modern detritus as guns, clocks, and model cars and planes alternating with rows of carefully arranged pieces of driftwood that resemble Stone-Age tools. The work caught the attention of critics, but Tateishi's next effort would be something completely different. As if determined to confound anyone's expectations, in 1964 he unveiled Like Tateishi Koichi, a billboard-like, Pop-colorful collage of elements that included Mt. Fuji, a creature from an Osamu Tezuka manga, and massive 3D letters (think Hollywood blockbuster movie titles) spelling out, in Japanese, "Community" and "Like Tateishi Koichi." In one corner, a tiny logo reads "Parodyrama." The critics lapped this up, too.

|

|

Like Tateishi Koichi (1964), watercolor on paper, Takamatsu Art Museum. |

During the sixties Tateishi further cemented his reputation by churning out more collages in a parodic vein that reveal a finger firmly on the racing pulse of postwar Japanese society as it underwent surges of economic growth and cultural schizophrenia. Works from this decade employ such recurring motifs as Japanese battle flags, locomotives, space capsules, atomic explosions, Godzilla, political figures, celebrities, and more often than not, Mt. Fuji. Also making an occasional appearance is MAD magazine mascot Alfred E. Neuman (Tateishi cited MAD as a seminal influence). A more cryptic motif is a fierce, lunging tiger with a huge glowing light bulb protruding from its head. Often accompanied by the visage of Chairman Mao, the tiger was Tateishi's symbol for China, which had recently conducted its first nuclear bomb test and was beginning to make its weight felt in East Asia. Like many young Japanese, Tateishi appears to have been both awed and unnerved by the forces unleashed by the Cultural Revolution, for the tiger and Mao images show up in many of his sixties works. Interestingly, he adopted "Tiger" as his pen name around this time.

|

|

The Great Clan (1966), oil on canvas, private collection. |

Tateishi then switched genres again, declaring that if he was going to make Pop Art, he might as well go back to his roots in the ultimate Pop medium, manga. Seemingly overnight he became a prolific cartoonist working in the conventional black-and-white sequential panel format. Mostly centered around brilliantly conceived gags, narrative and visual, his manga were so ubiquitous in the late sixties that many Japanese growing up during this time think of Tateishi primarily as a cartoonist. The generous gallery-ful of manga panels at the Chiba show is well worth the time it takes to peruse every one of them. Even more than the satirical paintings that preceded his manga period, this inexhaustible outpouring of gags and puns testifies to the madcap fecundity of Tateishi's mind. Did he ever sleep?

|

Illustration for Konnyaro Motors No. 5: Machine vs. Living Thing (1967), ink on paper, courtesy of Anomaly.

|

|

In the Beginning There Was Revolution (1970), oil on canvas, Takamatsu Art Museum. |

Inevitably, it seems, this newfound notoriety spurred Tateishi to defy expectations once again. Remarking on the misgivings he felt about the constant demand for his work and the healthy income he was beginning to make from it, Tateishi suddenly left Japan in 1969, moving with his wife to Milan, Italy, where they lived for the next 13 years. Very quickly he embarked on a series of oil paintings that used the sequential multi-panel format of manga to tell wordless stories that, while certainly not without humor, were more often abstract and surreal, the stuff of dreams. If anything they resemble the work of certain cartoonists who appeared in contemporaneous American underground comix like Zap (Victor Moscoso and Rick Griffin come to mind) -- so much so that one wonders if Tateishi wasn't exposed to them as he had been to MAD. Tateishi himself, however, wrote that many of his ideas during this period derived from British and American science fiction writers like Robert Sheckley, J.G. Ballard, and Robert Heinlein.

|

|

|

|

|

Micro-Fuji (1984), oil on canvas, Mori Art Museum.

|

In the Milan paintings, which are in many respects the most visually and intellectually satisfying of his oeuvre, Tateishi once more played with a stockpile of idiosyncratic motifs. But instead of the Zeitgeist-fingering Pop references of his Tokyo days, now he favored cosmic imagery, notably the moon and planets, which metamorphose over the course of multiple panels into such objects as cabbages, lemons, diamonds, roses, and human heads. People, too, morph into inanimate objects or alien entities. Living in Italy seems to have freed Tateishi from his fixation on Japanese cultural iconography; now he moved squarely into the territory of the subconscious at its most capricious, a la Magritte and Dali. But he was still not above tweaking the sensibilities of the art world, as with Tiger Guernica (1970), a shamelessly irreverent takeoff on Picasso's iconic antiwar statement. (Chairman Mao makes an appearance here, too.)

Talent will out, though, and Tateishi couldn't avoid commercial success for long in Italy, either. In addition to frequent gallery exhibitions, he was soon enjoying a steady stream of commissions for book illustrations, magazine covers, and even the occasional rock album. Once more, it appears to have become a bit much for the self-styled anarchist, because in 1982 he decided to pull up stakes again. Candidate destinations apparently included London and San Francisco, but for a number of reasons the Tateishis ended up moving back to Tokyo. They did not remain in the city for long, though. The couple moved out to the Chiba countryside in 1985 and settled in an old farmhouse that they refurbished themselves.

|

|

Illustration for A Tiger in the Land of Dreams (1984), acrylic on paper board, private collection. |

After returning to Japan, Tateishi began revisiting his past output, making prints of selected paintings and resuming his production of gag manga, but he also ventured into new media. In the mid-1980s he began making picture books at a pace of about one a year, and these are pure pleasure to look at. His debut publication, Tiger in the Land of Dreams (Fukuinkan, 1984), is a beautifully rendered, wordless tale of a green tiger's shape-shifting adventures (watermelons figure prominently). A concurrent series of colored pencil drawings, mounted on traditional hanging-scroll backings, is remarkable for its subdued, Nihonga-like coloration -- but the images themselves are as surreal as ever. At this point Tateishi seems to be giving full rein to a private language devoid of any real-world references the viewer might grab onto. Technically impeccable, his draftsmanship is at its zenith, but it is anyone's guess what he was thinking about.

Tateishi would indulge his fascination with the sweep of history once more in a 1990 triptych of monumental paintings summarizing the three imperial eras -- Meiji, Taisho, and Showa -- that followed the Meiji Restoration. Though these kitchen-sink collages are impressive for the sheer number of cultural touchstones they tick off, they lack the satirical punch of his sixties works, as if he had exhausted his store of irony and was content to let the images speak for themselves, like a good reporter.

|

|

Showa; an Adventurous and Nice Period (1990), oil on canvas, Tagawa Museum of Art. |

Tateishi's life came to an abrupt end in 1998 when he died of lung cancer at age 56. In his final years he had turned to yet another untried medium, clay sculpture. In 1995 and 1996 he turned out a series of bust-sized homages to artists he revered, among them Van Gogh, Gauguin, Cezanne, Picasso, De Chirico, Hopper, Miró, Rivera, Ryusei Kishida, and Taro Okamoto. Making the most of the solid format, Tateishi generally featured the subject's face on one side and filled the other three with 3D pastiches of representative masterpieces. Not only does Tateishi replicate the essence of each artist's style, he does so in sublimely imaginative compositions. Potato, a tribute to Van Gogh, offers a sculpted rendering of Sunflowers in front, while the back opens onto a miniature diorama of the The Potato Eaters sitting at their dinner.

Rear view of Potato (1996), ceramic, private collection, with a miniature sculpture of Van Gogh's The Potato Eaters. |

Tiger Tateishi's bewildering oeuvre has not always received the recognition it deserves, no doubt because he willfully ignored the arbitrary distinction between high and low art, inventing entirely new hybrids of manga and "fine" art like his cartoon-panel paintings. Once exposed to his work, one realizes that his influence on Japanese pop culture from the sixties on has been pervasive and inescapable. This retrospective provides ample proof of that. It is also knee-slappingly funny.

Although the Chiba show ends on 4 July, Tiger Tateishi: The Retrospective will travel next to the Aomori Museum of Art (20 July - 5 September), the Takamatsu Art Museum (18 September - 3 November), and then back to the greater Tokyo area at the Museum of Modern Art, Saitama / Urawa Art Museum (16 November 2021 - 16 January 2022).

All works by Tiger Tateishi; all images courtesy of the Chiba City Museum of Art. |

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for over 30 years. Since 2006 he has edited artscape Japan and written the Here and There column, as well as translating the Picks reviews. He also edits and translates works on Japanese architecture, music, and theater. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|