| |

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries, museums, and other cultural facilities around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

How Edo Became Tokyo: Time-Tripping at the Hibiya Library & Museum

Alan Gleason |

|

Tokyo Kanda Shrine Festival, nishiki-e woodblock print, Yoshifuji Utagawa, 1884 |

Chiyoda Ward is not just the geographic center of Tokyo, but its political/financial/cultural mecca as well. Positioned like the hole in the donut of ever-expanding circles that forms this megalopolis, it is home to the Imperial Palace, the National Diet Building, the Kasumigaseki district of government ministries, and the Otemachi financial district to boot. As Chiyoda goes, so goes Japan.

Thirty-six Views of Tokyo: Kudan Hill, nishiki-e woodblock print, Ikkei Shosai, 1871 |

Chiyoda's preeminent status has stood unchallenged for the four centuries since the Tokugawa shoguns built Edo Castle where the palace now stands. A study of the ward's history will therefore tell you much of what you need to know about the entire country from the Edo period on. So it is no surprise that the Chiyoda Public Library was able to rely almost entirely on materials about this one part of Tokyo to put together its current exhibition, a comprehensive look at the city's transition in the 1860s from Edo, seat of the Shogunate, to the modern imperial capital.

|

|

New Bird's-Eye View of Tokyo (detail), Ryusaburo Takebe, 1897 |

On display until 19 December at the Hibiya Library & Museum, flagship branch of the Chiyoda Library, Time Trip: From Edo to Tokyo utilizes its compact gallery space to good effect, guiding visitors on a tour that begins with the topography of Chiyoda and moves rapidly on to its first transformation, nearly overnight, from a sleepy fishing village into Japan's political center by the Tokugawa family, rulers of the nation in all but name. Completed in the early 1600s, Edo Castle dominated the district, and the rest of the country, until the Shogunate collapsed in 1867 in a coup d'etat engineered by a coalition of disgruntled provincial lords in western Japan. The new government claimed legitimacy through its allegiance to the emperor, whose powerless court had remained in Kyoto while the shogun ran the country from Edo. Once the Tokugawas had abandoned the castle (much of which had burned down a few years earlier, and had never been repaired), the Emperor Meiji -- still a teenager -- was installed in their place, moving into temporary quarters in what was now renamed Tokyo, the Eastern Capital, while a new palace was built where the castle had been. Thus began what is known as the Meiji Restoration, a period of full-throttle, even desperate modernization as Japan attempted to catch up with the Western powers.

|

|

Leaving the New Imperial Palace: Nijubashi Bridge, nishiki-e woodblock print, Ikuhide Kobayashi, 1889 |

Under the government's slogan of bunmei kaika (roughly "civilization and enlightenment"), vestiges of the old order were summarily discarded. Kimonos, topknots and swords gave way to Western suits and bowler hats. The wooden gates of the castle were torn down while buildings of brick rose in the new business district outside the moat. Frequent devastating fires had long bedeviled Edo, a city made entirely of wood, so the use of brick, as well as stone for bridges and other infrastructure, was part of a conscious effort to make the capital fire-resistant. Even the new Meiji Palace, though nominally traditional in outward appearance, boasted carpeting and chandeliers inside. By the late 1880s, a fully formed modern city was in place, replete with train lines, horse-drawn trams, gaslights, and a sewage system.

Pictorial Map of Bridges in Kanda, Eizo Kinoshita, 1985 |

The Hibiya show gives visual form to this remarkable transition through a wealth of maps, woodblock prints, and photographs. Then it goes one better by making use of state-of-the-art digital technology and artistic license to recreate what Tokyo must have looked like a century and a half ago. Entering a small side gallery, one is surrounded by a 360-degree view of downtown Tokyo, constructed from a set of photographs taken in 1889 from the Nikolai-do, a Russian Orthodox cathedral that had just been completed atop Chiyoda's highest hill. Paralleling this view, however, is the real coup de grace: an identical panorama, based on the 1889 photos but CG-jiggered to show Edo as it appeared before the Restoration. The CG reconstruction is based on documents from the last years of the Shogunate that provided details on the location of the huge daimyo mansions that dominated the neighborhood surrounding the castle.

|

|

Famous Scenes in Tokyo: View of Nikolai-do from Manseibashi Bridge, lithographic print, Sadajiro Ariyama, 1893 |

Also entertaining is a seven-minute video presentation of a parade of woodblock prints and old photographs portraying sites of interest in Edo/Tokyo and how they changed over time. One sequence features a number of still photos that have been converted into short "films" in which people, rickshaws, trolley cars and the like move realistically through the scene, thanks to some sort of digital magic.

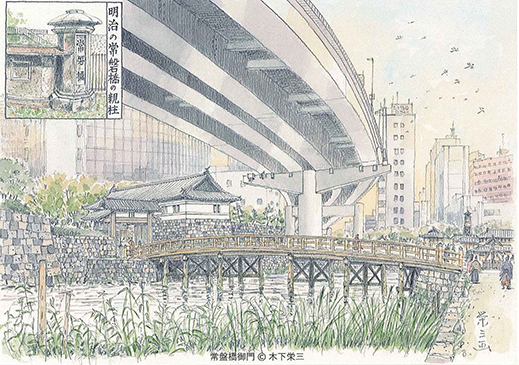

One of the most impressive efforts at juxtaposing old and new is a series of sketches by architect and illustrator Eizo Kinoshita, in which he depicts each of the historic 36 gates of Edo Castle (most of them long gone) against the Tokyo skyline as it appears today from the same vantage points. The contrast between these fragile wooden structures and the highrises towering above them (and, in some cases, expressways passing overhead) is, well, jarring. For what it's worth, similar sights can still be seen in Tokyo -- at the Hama Detached Palace, for example, whose gardens and teahouses are dwarfed by the wall of skyscrapers rearing up in the background.

|

|

Thirty-Six Gates of Edo Castle, New Edition: Tokiwabashi Gate, Eizo Kinoshita, 2014 |

This being a library, there is a heck of a lot of text to go with the exhibits, and it's all in Japanese. Even if you can't read the language, though, this is a magical history tour so profusely illustrated that you will learn plenty about Tokyo's precipitous leap from feudal bastion to world-class metropolis from the maps, prints and photos alone. Ukiyo-e, map, and old postcard buffs will be especially thrilled.

The Hibiya Library and its environs are themselves emblematic of the early stages of the capital's modernization process. The library sits in a corner of Hibiya Park, Japan's first Western-style urban oasis when it opened in 1903, and the original library building -- completed in 1908 and one of the country's earliest municipal public libraries -- was a stately Victorian-cum-Art-Nouveau structure. By contrast, the current building (finished in 1957) is a modernistic, glass-paneled, triangular affair. In the park just outside its doors, however, is a traditional Japanese garden with a pond that, as this goes to press, is surrounded by red momiji maples in full autumn glory. It's a good time to catch this show, then take a stroll amid a bit of the history it so vividly conveys.

|

|

|

|

|

|

"Tokyo City Hibiya Library" postcard, c. 1912 (left), and the Hibiya Library & Museum, 2011 (right) |

All images courtesy of the Hibiya Library & Museum.

|

|

| Time Trip: From Edo to Tokyo (in Japanese only) |

| 22 October - 19 December 2021 |

| Hibiya Library & Museum |

1-4 Hibiya Koen, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo

Phone: 03-3502-3340

Museum hours: 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Monday-Thursday and Saturday (to 8 p.m. Friday and 5 p.m. Sundays and holidays); closed on the third Monday of the month and during the New Year holiday

Access: 3 minutes' walk from Kasumigaseki Station on the Tokyo Metro Marunouchi, Hibiya and Chiyoda Lines

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for over 30 years. Since 2006 he has edited artscape Japan and written the Here and There column, as well as translating the Picks reviews. He also edits and translates works on Japanese architecture, music, and theater. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|