|

|

|

HOME > HERE/THERE >Man with Two Hats: Toshio Iwai at the Museum of Modern Art, Ibaraki |

|

| |

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries, museums, and other cultural facilities around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Man with Two Hats: Toshio Iwai at the Museum of Modern Art, Ibaraki

Alan Gleason |

|

Sketch and final version of an illustration in A House of 100 Stories (2008) |

Toshio Iwai began drawing his most famous book because his young daughter was struggling to memorize numbers from 1 to 100.

As the artist recounts it, his solution was to create a picture book in which each number was represented by a floor in a 100-story house. Shown in cross section, the floors were populated by animals engaged in various amusing activities. Thus was born one of Japan's best-selling and most beloved picture books, A House of 100 Stories. The illustrations from this book and its four sequels to date are the big draw for visitors of all ages at an exhibition now up at the Museum of Modern Art, Ibaraki.

Titled Which one's which? Iwai Toshio: A Retrospective: "A House of 100 Stories" and Media Art, the show highlights the duality of Iwai's professional career. Born in 1962, he had already made his mark as a media artist when he published his first picture book in 2006. A House of 100 Stories, which appeared in 2008, immediately won him a new fan base of young readers and their parents, cementing his place in the pantheon of great picture-book artists from Japan. As its title suggests, the exhibition plays with this dual identity, giving equal weight to both Iwai's kiddie-lit output and his more "adult" (but just as playful) art installations.

Toshio Iwai, picture-book author (left) and media artist (right) |

It quickly becomes obvious that these seemingly disparate spheres of activity are shaped by the same wildly unfettered, childlike imagination, one that offers up a seemingly endless parade of gags and gadgets. The seeds for Iwai's creative fecundity were sown in his childhood, we are told. Growing up in a middle-class household in suburban Nagoya, he got teased by siblings and schoolmates for being clumsy and accident-prone, but found that he excelled at building and drawing things. Fond of manga and anime, and of taking things apart and putting them back together, he was making his own animated flip books and motor-driven mechanical toys while still in elementary school. He found direction for these proclivities when he enrolled in the University of Tsukuba (not far from Mito, where the museum is located) and majored in plastic art and mixed media. There he began making installations that melded old animation techniques like the zoetrope with state-of-the-art video and computer technology. In 1985, while he was still at Tsukuba, his video installation Time Stratum II made him the youngest recipient ever of the Grand Prize at the Contemporary Japanese Art Exhibition.

|

|

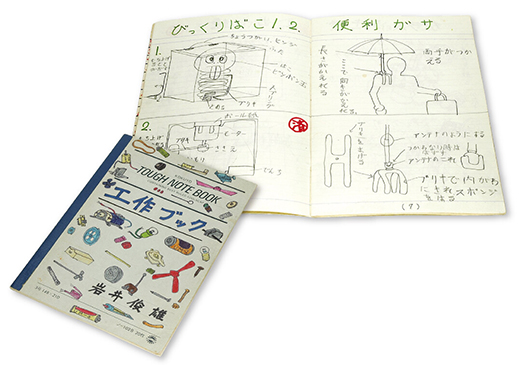

Cover and pages from "Workbook / Toshio Iwai" (c. 1973). The pages show his sketches for a motorized jack-in-the-box (left) and a "handy umbrella" (right). |

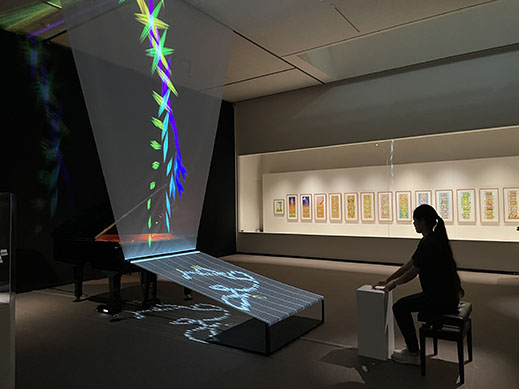

After graduation, Iwai began to garner acclaim both at home and abroad for his interactive media works. One of the most celebrated is Piano - As Image Media, which he created while living in Germany in 1995. A trackball interface allows the user to generate musical "notes" in the form of dots on a screen linked by computer to a grand piano, which plays the keys corresponding to the dots while colored lights rise into the air in time to the notes on another screen suspended above the keys. Occupying its own gallery, this installation is the interactive high point of the exhibition, drawing a steady stream of visitors young and old to work the trackball. The sounds produced on the piano are surprisingly harmonious, which made me wonder why we weren't hearing a more chaotic mishmash of white and black keys -- apparently Iwai chose to avoid that sort of cacophony by letting the computer play only the white ones. Fans of avant-garde music may be disappointed, but the result is certainly less grating on the ears.

|

|

Installation view of Piano - As Image Media (1995) |

Even as he made a name for himself as a media artist, Iwai was also parlaying his skills into video game production and digital design, earning him commercial as well as artistic success. Meanwhile, he continued to channel his inner kid -- developing, for example, a popular interactive children's TV program, Ugo Ugo Lhuga, that was inspired by the iconic American series Pee-Wee's Playhouse. When his daughters were born, he says, building toys for them, just as he had done for himself as a boy, came naturally. This brought him back to the analog world of paper, wood, and cardboard. The Ibaraki show features a roomful of these handmade wonders, ranging from gargantuan stuffed animals made out of futon to big cardboard dollhouses displaying the wares of a bakery, a bird shop, and more. From there it was not such a great leap to picture book production.

Installation view of handmade toys by Toshio Iwai, with futon-stuffed animals in the foreground |

Iwai's first publication for kids, in 2006, was Dotchi ga hen? (roughly, "Which one's weird?"), a collection of flash-card-like panels showing two images side by side that are similar, but contain amusing discrepancies for the young reader to identify. (The exhibition's title, Which one's which?, borrows from that of another book in the same series.) It was not until the 2008 debut of the first 100 Stories volume, however, that his second career took off in earnest.

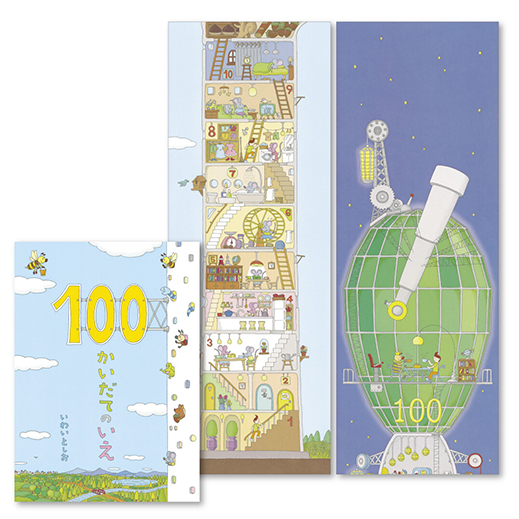

The tale begins when Tochi, a young boy who is fond of stargazing, receives an anonymous letter inviting him to visit the top of a 100-story house deep in the forest. Entering on the ground floor, he climbs up the stairs one story at a time, encountering various woodland creatures engaged in everyday pursuits. Every ten floors the species changes: a family of mice on the 1st through the 10th is followed by squirrels, frogs, ladybugs, snakes, and so on. The denizens of the topmost ten stories are spiders, whose eight limbs enable them to operate the machinery that moves a huge telescope on the 100th floor, through which Tochi can gaze at the stars to his heart's content.

|

|

Cover and illustrations from A House of 100 Stories (2008, Kaisei-sha) |

Assigning a different creature to each decade of floors is a good way to teach children to group numbers in tens. But what really captures their interest is the unfolding of one hilarious scenario after another from floor to floor. Most of the critters' activities are cutely anthropomorphic -- they cook, bathe, watch TV, do their laundry in a washing machine -- but Iwai cleverly intersperses these scenes with others of animals engaged in more animalistic behavior. The mice work out on large wheels; the squirrels store a vast hoard of nuts in their pantry; the woodpeckers saw lumber when they get tired of pecking at it; and the bats spend their lives hanging upside down, even when they are sitting on the toilet. Every one of the 100 floors is indeed its own "story," and every one merits close inspection.

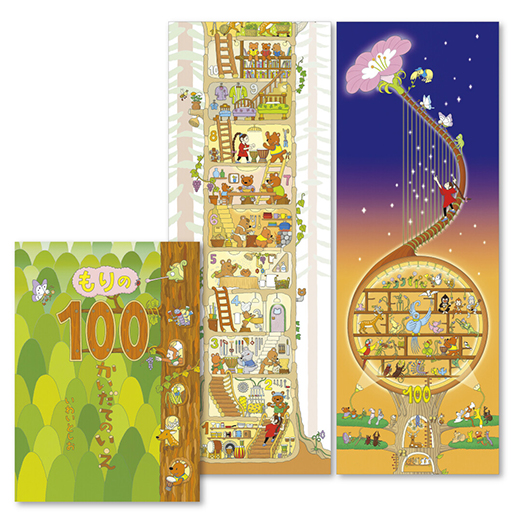

Since that initial hit, Iwai has gone on to publish four more volumes in the 100 Stories series, each with a new twist on the original premise. The second, An Underground House, is inhabited by hedgehogs, lizards, raccoons and the like, while An Undersea House introduces all manner of marine life. In the fourth book, A Sky House, Iwai departs from his formula by populating the floors with atmospheric phenomena -- raindrops, rainbows, clouds, lightning, and at the top, the sun itself -- all magically transformed into animate creatures living their lives in highly creative ways. For A Forest House of 100 Stories, published this year, the author came up with a variation on the woodland setting of the first volume. Here the protagonist, a young girl named Oto who plays the harp, discovers a tall tree full of musicians: the bears play drums; the deer, castanets; the praying mantises, violins made of tree leaves; the monkeys strum guitars and the walking sticks play flute. At the very top is a glorious karaoke penthouse outfitted with microphones by -- who else? -- songbirds, who contribute the vocals when everybody gathers there for a jam session.

|

|

Cover and illustrations from A Forest House of 100 Stories (2021, Kaisei-sha) |

What makes the Ibaraki presentation especially pleasurable is that it showcases every page of these books in easy-to-scrutinize, poster-size reproductions, alongside sketches and drafts showing how Iwai mapped out the rough ideas for each floor, then polished them as he went along, adding new, even wackier details as they occurred to him. Copies of the actual books are on display and for sale, of course -- both in standard picture-book format and in compact paperboard editions that facilitate flipping the pages upward from the 1st to the 100th story.

When I visited the museum on a quiet weekday afternoon in late August, while schools were still on vacation, I was surprised to run into a sudden influx of teenagers, dressed in school attire and evidently on some kind of class assignment. The enthusiasm with which they pored over the 100 Stories art or played Iwai's piano made it clear that his protean imagination has the power to thrill the inner child in all of us, from 1 to 100.

|

|

The Museum of Modern Art, Ibaraki, next to Lake Senba in Mito |

All works shown are by Toshio Iwai; all images courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, Ibaraki.

|

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for over 30 years. Since 2006 he has edited artscape Japan and written the Here and There column, as well as translating the Picks reviews. He also edits and translates works on Japanese architecture, music, and theater. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|