Installation view, Part 3 of the Sotaro Miyagi exhibition, Setagaya Art Museum |

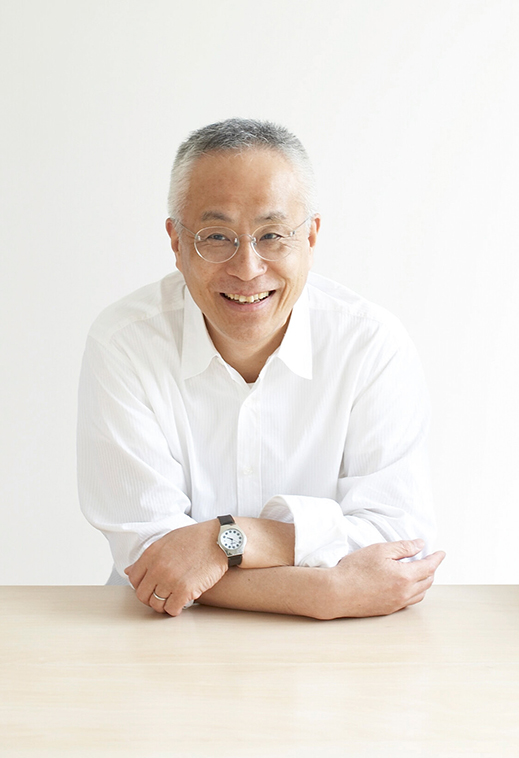

If you live in Japan, or have occasion to visit a Japanese office, look around -- you are very likely surrounded by the work of Sotaro Miyagi, who just might be the most prolific product designer in history. In his relatively brief 35-year career (he died prematurely at age 60, in 2011), Miyagi designed everything from cameras and kitchenware to soap dishes and staplers. From the late eighties on he was Tokyo's go-to consultant on every conceivable genre of design -- product, graphic, package, signage, spatial. Most impressive of all, he brought the same commitment and laser focus to paper cups as he did to massive urban redevelopment projects -- and all out of a virtually one-man office.

Product design is not the sexiest topic one might associate with an art museum exhibition, but the Setagaya Art Museum, in southwestern Tokyo, has produced a retrospective, Miyagi Sotaro: The Useful and the Beautiful, that makes the case for Miyagi the designer as a creative force, even an artistic one. Miyagi was a champion of the "less is more, keep it simple" ethic, and his designs -- whatever the medium -- come in streamlined, no-nonsense forms that prioritize function yet still appeal to the eye. Simplicity is no easy thing to maintain, now more than ever when designers seem to take fiendish delight in piling more bells and whistles onto every new product, whether it's a smartphone or a vacuum cleaner.

Installation view, Part 1 of the Sotaro Miyagi exhibition, Setagaya Art Museum |

|

|

|

|

|

"allround bowls" cooking equipment (Cherry Terrace, 2005)

|

Upon entering the first gallery at the Setagaya show, however, one's own eyes may well glaze over, as mine did, at the row upon row of small objects covering a vast expanse of tables. Categorized by the manufacturing concerns that commissioned the designs (most of them household names in Japan like office equipment and stationery makers Plus and Askul), these arrays at first glance exude all the charm of a garage sale, and seem just as randomly laid out. At the first table, for example, we encounter several models of the Fujica camera that was one of Miyagi's earliest projects, followed by a lineup of fairly nondescript cooking bowls, strainers and salad spinners. Later, however, an image of the same vessels stacked into what can only be described as a space-age art object (see the photo here) reveals that they form a handsome and compact nested set of "allround bowls" commissioned by the Cherry Terrace company.

As one progresses deeper into the exhibit, the eye begins to zero in on items that look very familiar indeed. Here you will find the tissue-paper boxes and toilet paper rolls at your house, the "prescription memo" booklet you receive from your neighborhood doctor, and EVERYTHING at your office: air cleaners, desk lamps, glue sticks, document files, copy paper packaging, you name it. And then there are the mini-staplers -- those tiny bug-like devices in pastel colors that occupy every desk drawer in Japan. Judging by the selection at the Setagaya show, Miyagi was the nation's stapler king, designing countless models in a dizzying parade of styles (all, it seems, for the Plus company, which appears to have cornered the stapler market). Lined up together, they resemble the industrial equivalent of a butterfly collection.

"Flat Karu-Hit" stapler (Plus, 2006) |

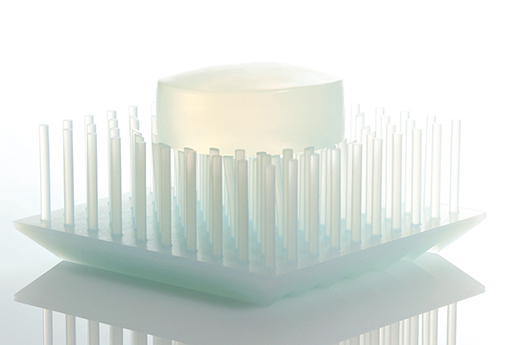

In another gallery, certain products are singled out for special attention, and this allows us to appreciate more fully the creative flair Miyagi brought to his craft. A set of multicolored plastic toothbrushes in its own vitrine testifies to the beauty he could instill in the mundanest of household items. Perhaps his most sublime creation is "Tsun Tsun," a translucent plastic soap dish that could hold its own in an exhibition of contemporary sculpture.

|

|

+d "Tsun Tsun" soap dish (h concept, 2004), in collaboration with Mirei Takahashi |

A number of text panels on the gallery walls offer quotations (unfortunately only in Japanese) from Miyagi that articulate his philosophy of design. Above all he was concerned with serving users' needs, and believed that one could design an attractive, even inspiring product as a natural outcome of this priority -- an attitude encapsulated in the concept yo no bi, or "beauty of function," espoused by founders of the Mingei folk-craft movement. Modest about his own prodigious output, Miyagi demurred that "You don't have to think too hard about a design if you know what the product requires."

|

|

|

|

|

Sotaro Miyagi (1951-2011)

|

Miyagi was already suffering from terminal cancer when he wrote a brief memo to his students in a university class he taught on product design theory. In it he called on designers to focus on "the true value of things" and to work "for the sake of human happiness." He also admonished them to keep in mind the larger implications of living in an information-saturated society. The paramount issue we face today, he declared, is how to process the incessant flood of incoming information and convert it not just to "knowledge" but to "wisdom." These prescient words, a valedictory of sorts, are laid out in a terse, outline-like format on a single page. Even in his writings, Miyagi pursued the virtues of brevity and efficacy in the service of a profoundly humanistic approach to design. Those same qualities make his works as fresh and appealing today as they were when he created them.

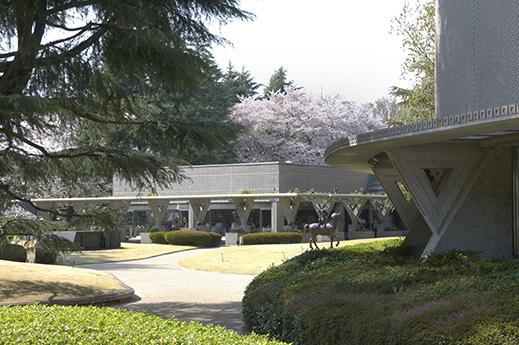

The Setagaya Art Museum is a modernist structure with banks of picture windows facing Kinuta Park, one of Tokyo's largest green spaces. Complementing a look at this exhibition with a leisurely stroll among the trees is an excellent way to spend an autumn afternoon.

|

|

The Setagaya Art Museum looks out on Kinuta Park, a beautiful location whether in spring (shown here) or autumn. |

All images courtesy of the Setagaya Art Museum.

|

|

| Miyagi Sotaro: The Useful and the Beautiful |

| 17 September - 13 November 2022 |

| Setagaya Art Museum |

1-2 Kinuta-koen, Setagaya-ku, Tokyo

Phone: 03-3415-6011

Open 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.; last entry 30 minutes before closing

Closed Mondays

Admission by online reservation and advance ticket purchase only

Access: 17-minute walk from Yoga Station on the Tokyu Denentoshi Line, or take the bus for Setagaya Bijutsukan from Yoga Station to the "Bijutsukan" stop

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for over 30 years. Since 2006 he has edited artscape Japan and written the Here and There column, as well as translating the Picks reviews. He also edits and translates works on Japanese architecture, music, and theater. |

|

|

|

|