Yoshimatsu Goseda, Suruga Bay (year unknown), Kasama Nichido Museum of Art |

I like trains, and I especially like Tokyo's railways, since I grew up riding them. I have vivid memories of the Chuo and Yamate (now Yamanote) Line trains I took to the American School downtown in the late fifties. The cars were dark brown inside and out, gloomy but with warm wooden fixtures. War veterans with missing limbs often made their way from one end to the other, playing accordions and begging for money. A decade had passed since the end of the war, but its vestiges were everywhere. Like any six-year-old I took everything around me for granted; this was the world as I knew it. The trains were a big part of that, and once I figured out you could go anywhere and back on a one-station ticket (10 yen!), I would ride around on them just to look at the passing scenery.

Shohachi Kimura, Shinjuku Station (1935), private collection |

The exhibition currently at Tokyo Station Gallery transported me back to that world. Art and Railway -- 150th Anniversary of Railway in Japan [sic] is a rail and nostalgia buff's paradise, covering as it does just about every kind of art having anything to do with trains since the first ones arrived in Japan in the waning days of the Edo shogunate. To commemorate the titular anniversary, the curators have picked out exactly 150 works for display. It's a generous and rewarding selection.

Rinsaku Akamatsu, Night Train (1901), Tokyo University of the Arts |

Most of the works treat trains and railroads as metaphors for modernity and the good life, particularly during Japan's years of headlong industrialization in the Meiji era (1868-1912). But trains seem to appeal to artists of all eras and genres, so this diverse assemblage of paintings, sketches, and photographs serves as an excellent crash course on art in post-Edo Japan, starting with ukiyo-e but quickly moving into Western-style yoga painting -- Realist, Impressionist, Fauvist, Cubist, and on and on. The chronological presentation carries us briskly through the decades until we are viewing photos of commuters crammed into rush-hour Tokyo subways or avant-garde happenings staged on station platforms. In the bargain, we get a concise lesson in modern Japanese history.

|

|

Utagawa Hiroshige III, Steam Locomotive on the Yokohama Waterfront (1874), Kanagawa Prefectural Museum of Cultural History |

Japan's railroad romance begins with two miniature steam locomotives introduced from abroad. The first arrived in Nagasaki on a Russian ship in 1853, while the second came to Yokohama in 1854 aboard one of Commodore Perry's black ships. Ukiyo-e artists promptly rose to the occasion, churning out colorful and sometimes fanciful renderings of the bizarre smoke-belching machines. The first known drawing of a train in Japan appeared in 1854; by 1871 ukiyo-e masters like Tsukioka Yoshitoshi were foregrounding locomotives in their portrayals of a nation in the throes of change. One of the most curious compositions of this period is a painting by Kawanabe Kyosai of a phantasmagoric heaven-bound railcar being greeted by divine emissaries (this was commissioned, we are told, by a patron whose daughter had recently died). Utagawa Hiroshige III commemorated the opening of Japan's first railway terminus at Shinbashi, Tokyo, in 1872 -- the same year, the exhibition points out, that a new Japanese word, bijutsu, was coined for fine art.

|

|

Kawanabe Kyosai, A Steam Locomotive Bound for Heaven, from Journeys through Heaven and Hell (1872), Seikado Bunko Art Museum |

The earliest known presence of a train in a Western-style work was in 1873, when a wisp of locomotive smoke made its appearance in a landscape sketch by Yuichi Takahashi. There followed a flood of train-themed yoga, mostly of the Impressionist sort. For some reason many of these works featured Tabata Station, then a rural backwater on the northern outskirts of Tokyo, perhaps because the neighborhood was a favorite haunt of artists and writers. By the 1920s train art was everywhere, ranging from the commercial designs of Hisui Sugiura, who produced a chic Art Deco poster celebrating the opening of "East Asia's first subway" in Tokyo in 1927, to the boldly modernist efforts of painters like Toshiyuki Hasekawa, whose wild and woolly Engine House (1928) is one of the centerpieces of this show.

Toshiyuki Hasekawa, Engine House (1928), The Railway Museum |

By the 1930s the country was in the grips of the militaristic fervor that would lead it into a disastrous war. Artists were still painting scenes of trains passing through bucolic landscapes and docile passengers standing in crowded carriages, but one of the most striking images in this exhibition is a photo taken in 1937 by police photographer Koyo Ishikawa of a send-off ceremony at Shinagawa Station for hundreds of soldiers, presumably heading for the China front. It is a unique shot because it captures the military event from a higher vantage point; soon afterward such camerawork would be banned for security reasons.

|

|

|

|

|

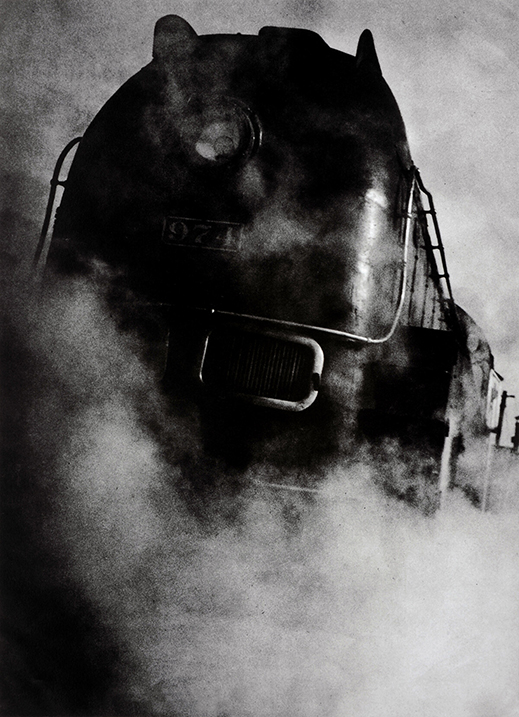

Seibo Tanaka, Locomotive (1937, printed in 2017), Nagoya City Museum, a heroic photo-portrait of the Asia Express on the South Manchurian Railway

|

During the war, the military government favored paintings and photographs of rushing locomotives and hard-working engineers and firemen. One recurring motif was the monstrous black engine of the South Manchurian Railway's Asia Express, which ran between Dalian and Changchun, capital of Japan's puppet state of Manchukuo.

With defeat and the lifting of censorship, artists felt free to chronicle the hardships of postwar life, and many portrayed the throngs jamming trains from the provinces that took them to the capital in search of work. One of the most sobering exhibits here is a set of a dozen sketches by Teruo Sato of homeless people sleeping in the underground passages of Ueno Station, the Tokyo terminus of the northern lines. Sato drew them over a period of years, from 1947 to 1956, when much of the city's housing stock had yet to be replaced after its incineration in the firebombings.

The economic rebound of the sixties spurred other sorts of train-inspired creativity. When the first bullet train took off on its inaugural run in 1964, a group of artist provocateurs paraded around Tokyo Station with large canvases bearing satirical commentary on the event. By the 21st century things were taking a more apocalyptic turn, as exemplified by Hisaharu Motoda's Indication - Tokyo Station (2007), a meticulously rendered fantasy of the great brick terminal in ruins following some unnamed catastrophe.

|

|

Minoru Hirata, Street Walking Exhibition and the Commuters between Tokyo Station and Kyobashi (by Hiroshi Nakamura and Koichi Tateishi) (1964), Tokyo Station Gallery |

Bringing us up to the present is a surprising treat: the original Level 7 canvas by the guerilla art collective Chim↑Pom, which surreptitiously installed it in Tokyo's bustling Shibuya Station in 2011. A depiction of the melted-down reactors in Fukushima, it was designed to fit flawlessly (and almost undetectably) into a corner of Taro Okamoto's mural Myth of Tomorrow, an anti-nuclear magnum opus that adorns the station wall. (Chim↑Pom's addition stayed up for two days before it was noticed by station personnel, and Okamoto's estate declined to press charges.) Railways, it would seem, have become not only vehicles but venues for artistic expression.

Installation view, Art and Railway -- 150th Anniversary of Railway in Japan. At center are 12 sketches by Teruo Sato from A Sleep in the Underpass (1947-1956). The original brick walls, which were uncovered during the station's restoration, provide an atmospheric backdrop for the exhibits. Photo © Hayato Wakabayashi |

Occupying a corner of Tokyo Station's Marunouchi terminal building, Tokyo Station Gallery is certainly the perfect venue for this show. To enter it, one passes through the huge rotunda under the Marunouchi North Dome. More of a museum comprising many small exhibition rooms than a gallery, it occupies three stories connected by a spiral staircase enclosed in a brick wall and topped off by a cupola. This is not faux-retro architecture but the real thing, lovingly restored just ten years ago to the glory of the original terminal building, which dates back to 1914 and was partially destroyed in a 1945 air raid. The multi-domed Victorian free-classical façade (it bears an uncanny resemblance to Amsterdam Central Station) runs the length of Tokyo Station on the Marunouchi side facing the Imperial Palace. The gallery, which initially opened in 1988 in another part of the terminal, moved to its present site when the station's renovations were completed in 2012.

This fortuitous location means that after viewing the exhibition, you can walk straight out onto a balcony under the dome and watch the crowds scurrying in and out of the ticket wickets below. Then you can head outside and take in the panorama of the entire Marunouchi façade, a work of art in itself.

(Note: There are no English-language commentaries posted next to the gallery exhibits, so be sure to pick up the English handout at the entrance, or download it here.)

|

|

Exterior view of the Marunouchi North Dome of Tokyo Station. The gallery occupies the three floors between the octagonal rotunda and the small cupola at far left, which caps the gallery's spiral staircase. |

All photos courtesy of Tokyo Station Gallery.

|

|

| Art and Railway -- 150th Anniversary of Railway in Japan |

| 8 October 2022 - 9 January 2023 |

| Tokyo Station Gallery |

Marunouchi North Dome, Tokyo Station, 1-9-1 Marunouchi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo

Phone: 03-3212-2485

Open 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. (to 8 p.m. Friday); last admission 30 minutes before closing

Closed Monday (or Tuesday if Monday is a public holiday), during the New Year holidays and exhibition changeovers

Access: The museum is located just outside the ticket gates at the north exit on the Marunouchi side of JR Tokyo Station.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for over 30 years. Since 2006 he has edited artscape Japan and written the Here and There column, as well as translating the Picks reviews. He also edits and translates works on Japanese architecture, music, and theater. |

|

|

|

|