|

Set aside plenty of time for the Shirai retrospective -- it occupies a vast space of which only part is shown here. Home to Japan's largest collection of paintings and prints by Georges Rouault (1871-1958), Shiodome Museum regularly holds special exhibitions like this one on architecture and design.

|

Though his was hardly a household name, ask nearly any practicing architect of any age in Japan about Seiichi Shirai (1905-83), and the response is consistently one of admiration, if not reverence. An ardent philosopher, poet, and calligraphist whose life spanned an age of ever-increasing industrialization, Shirai the architect holds a special place in the hearts of designers today for the markedly individual and spiritual stance that informed his many works. At Panasonic Electric Works' Shiodome Museum through March 27, Sirai -- Anima et Persona is a far-reaching retrospective that examines the man's legacy through his architecture, essays, brushwork, and even little-known book designs.

The exhibition pays homage to its subject right down to such lovingly curated details as the Beethoven string quartets and piano sonatas (his personal favorites) that play in the gallery's background, or the beaded metal strings (replicas of those he used in his acclaimed work for Shinwa Bank) that gently partition its spaces. Conceptually the program explores the main categories of Kohakuan (Shirai's private residence), Ju (dwellings), To (monuments), Genbakudo (Temple Atomic Catastrophes), Maboroshi (visions), Kyo (public works), and Inori (prayer) -- each section replete with sketches, models, calligraphic works, and photographs. Original graphite drawings of floor plans, elevations, and perspectives -- exquisitely rendered by hand -- are striking in their detail and recall a not-so-distant past before the proliferation of CAD and other computer-based documentation tools. This is architecture as craft, the very ideal Shirai championed.

|

|

|

An intimate partitioned space is dedicated to Genbakudo (Temple Atomic Catastrophes), considered by many to be Shirai's signature masterpiece. At center on the far wall is a graphite perspective drawing of the proposed monument, stunning for its textured clarity.

|

|

This birds-eye perspective from 1955, hand-drawn in pencil, reveals the symbolic mushroom-cloud shape of Shirai's proposed Genbakudo. |

|

|

|

| Over the colossal entranceway to Shinwa Bank's headquarters (1975) in Sasebo, Nagasaki prefecture, Shirai had the cautionary words "All that glitters is not gold" carved in Latin. The 41-meter-high façade is finished in locally quarried stone. Photograph by Osamu Murai |

|

An interior view of the Serizawa Keisuke Art Museum in Shizuoka (1981) highlights Shirai's trademark blending of Japanese and Western aesthetics. Typical of his designs, the space is at once warm and cathedral-like. Photograph by Osamu Murai |

One of the most captivating hand-drawn works on display is the carefully rendered perspective drawing, in graphite on tracing paper, of Shirai's 1954 design proposal for Genbakudo, a nuclear memorial that was never realized. It and a few other diagrams comprise what was Shirai's voluntary response to a newspaper article from which he had learned that the artists Iri and Toshi Maruki were hoping to find a permanent home for their Genbaku no Zu (Hiroshima Panels). Now a monumental collection of 15 murals depicting the horrors of the atomic bombings, at the time they were still a series in progress. Shirai did not know the Marukis, nor was he familiar with these works that have since become a world-renowned symbol of peace education, but it is not surprising that he was drawn to the artists' plea. In his proposal he sought a purity of form that would express the universality of all living things over and above the illusory wholeness of the nation-state or, for that matter, of civilization itself. In his words, he wished it to be "an eternal, collective symbol of hope rather than a metaphor for the memory of a tragedy." He envisioned a cantilevered cubic volume, detached from its entrance pavilion and sitting low above a quiet pool of water on a single thick cylinder. The approach to this separate hall would be via a passageway tunneled beneath the pond and lit midway by a single skylight. When seen from above, the overall program of pavilion, pond, and rounded plaza together form the shape of a mushroom cloud, reminding us of our shared responsibility in an atomic age.

Shirai disassociated himself from prevailing theories and philosophies of modernism, which is perhaps one reason why his name did not share the high-profile limelight of many of his contemporaries during Japan's great post-World War II push to modernize. And while many of his residential designs, his extensive work for Shinwa Bank in Sasebo, Nagasaki prefecture, and numerous buildings in Akita prefecture still stand, others have succumbed to the wrecking ball -- sad irony for an architect whose vision of modernity was all about enduring connections to the heart and soul. In Tokyo, the main hall of Zenshoji temple (1958) in Nishi-Asakusa, Azabudai's iconic Noa Building (1974) at Iikura crossing, and the Shoto Museum of Art (1980) in Shibuya are accessible to public view. That's all the more reason to savor this in-depth look at his oeuvre now, while you can. After its Tokyo run, Sirai -- Anima et Persona will move on to the Kyoto Institute of Technology Museum and Archives from May 23 to August 11.

|

|

|

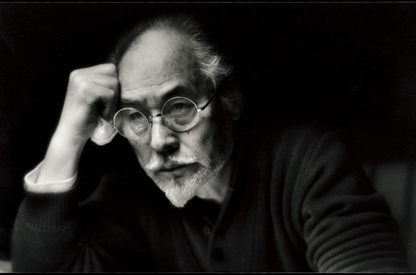

Left: Shirai in 1978. A designer whose language was gravitas, memory, and art, he drew from the wide stream of consciousness that links us all, seeking the noble truths within. Photograph © Keiichi Tahara / © Sirai Architectural Institute

Right: Shirai practiced calligraphy assiduously for more than 20 years until he died, sometimes for eight or more hours a day. The work shown above at right, from a date unknown, reads Myoshin, a Buddhist term for the "non-judgmental, essential spirit."

All images courtesy of Rouault Gallery

|

|