|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese art critics living in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Unleashing the Museum: Chu Enoki

Christopher Stephens |

|

|

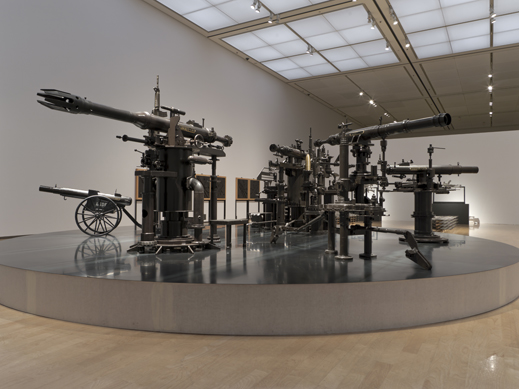

| Group of cannons: Cannon No. 1 (1972), Falcon C2H2 (2007), Kamui 77.5mm C2H2 (2008), Salute C2H2 (2008), metal |

Frequent visitors to museums are accustomed to being confronted with difficult imagery that a less experienced viewer might find shocking or obscene. While Chu Enoki never resorts to blood and guts, or even a single sex organ, there is something deeply unnerving about his work. It is perhaps the lack of visible human forms and Enoki's seeming deification of all things metal and mechanical that fills Unleashing the Museum (running through November 27 at the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art) with such a strong sense of foreboding.

Born in Kagawa Prefecture in 1944, Enoki began showing his paintings after coming to Kobe in the early '60s, but his first notable works were the events he staged alone and with a group called Japan Kobe Zero in the early '70s. In a 1970 performance, for example, he strolled through Japan's first "pedestrian paradise" (in Tokyofs Ginza) on opening day clad only in a loincloth, a hat, and the insignia of the Osaka Expo (which was underway at the time) suntanned onto his stomach. He was arrested a few minutes later. With Japan Kobe Zero, Enoki helped organize Revolution of the Rainbow, a happening in which some 150 "rainbow people" performed a series of actions premised on the notion that they had a life expectancy of one day. This event included a mock hanging of several of the participants that was held in the middle of the street next to a shopping arcade in downtown Kobe.

After leaving Japan Kobe Zero in 1976, Enoki embarked on a long-term project called Went to Hungary with Hangari in which he began by cutting off all of the hair on the right side of his body (i.e., hangari or "half-cut") and making a short trip to Budapest. He went about his business in that state for the rest of the year. Then Enoki shaved off all the hair on his head and face, and after letting it grow back for a year and a half, repeated the process by cutting off the hair on the left side of his body.

In the early '80s, Enoki began concentrating primarily on works that he assembled out of scrap metal or machine parts, such as a 13-meter-long, 250-ton sculpture titled Space Lobster P-81. Consisting of components from boats and trains but exuding an otherworldly air, the vessel, which had purportedly been sent from the planet Lobster, emitted smoke and the recorded message "The earth's garbage will be returned to it."

|

|

|

| Cartridge (1991-2011), cartridges |

|

Test Piece (2011), steel |

Though not always apparent, one of Enoki's central themes is the creation of things, such as weapons, that are often seen as abhorrent but are an undeniable product of human ingenuity. Referencing the atomic bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Little Boy U235 / Fat Man Pu239 (1982/1983), for example, was made up of two daunting-looking black devices suspended in midair that threatened to explode if they touched each other. The artist has also created a series of functional cannons (some with a more traditional appearance, some a complex assemblage of recycled machine parts), which he fires in performances to commemorate the opening of an exhibition -- as he did in October in Kobe.

Two other frequent Enoki motifs, both of which are on prominent display at the Hyogo Museum, are huge snaking mounds of spent cartridges and dozens of silver cast-iron machine guns standing upright in a line. As these works are presented without irony or any hint of criticism, it is tempting to interpret them as a glorification of military might, but this is clearly not Enoki's intent. Refusing to oversimplify the issues, he attempts to deflate these loaded images and challenges us to view the manmade objects as totems of our time and civilization, and as things that possess a haunting, albeit repulsive, beauty.

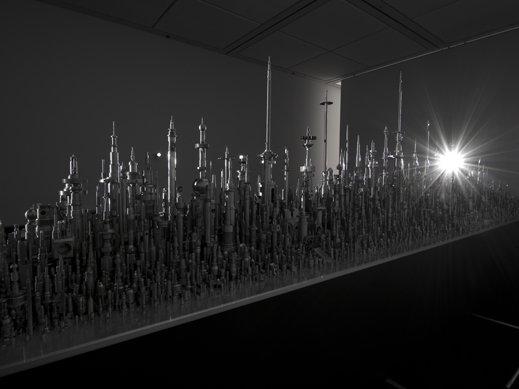

Supporting himself by working as a lathe operator for many years until his retirement in 2004, Enoki has a familiarity with steel that underlies his career as an artist. Nowhere is this more apparent than in RPM-1200, generally considered to be his most accomplished work. Erected on a large pedestal are thousands of metal rods and cylinders, which from a distance have the appearance of a strange, futuristic city. But rather than molding or altering the parts to fit his sculptural needs, Enoki has left them in their original form, transforming them into an artistic creation merely through a meticulous arrangement and combination of shapes -- an approach that is emblematic of his recent work.

Not as well known as it should be (due perhaps to the controversial and easily misunderstood nature of his creations), Chu Enoki's work, once unleashed in your mind, is nearly impossible to forget.

|

RPM-1200 (2006-2011), metal

All photos by Seiji Toyonaga; images courtesy of the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art

|

|

|

|

Christopher Stephens

Christopher Stephens has lived in the Kansai region for close to 25 years. In addition to serving as the editor of the now defunct magazine Kansai Time Out for many years, he has extensive experience as the translator of numerous exhibition catalogues for museums throughout Japan, and art and architecture books such as What's Gutai?, The Architecture of E.G. Asplund: 1885-1940, Salon to Biennial, World Architects 51, Miwa Yanagi: Windswept Women, Tomoko Konoike's Inter-Traveller, and Tadanori Yokoo's Tokyo Y-Junctions. |

|

|

|