|

|

|

HOME > FOCUS > The Art of Healing, at the National Museum of Nature and Science |

|

|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese art critics living in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

The Art of Healing, at the National Museum of Nature and Science

Susan Rogers Chikuba |

|

|

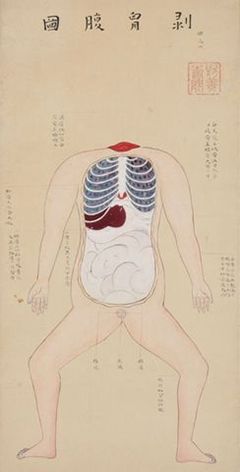

| Early Chinese depictions of the five viscera and six entrails, like the example at left, had less to do with anatomical accuracy than with illustrating prevailing beliefs about energy flow. Dolls like the 18th-century one at right, believed to be the only one extant, were produced in Japan in response to European anatomical texts that revealed new insights to the body's workings. They were displayed at apothecary shops and otherwise used to educate and awe Edo-period citizenry. Medical collection, National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo |

Historical surgical implements, wooden dentures, medical texts, centuries-old bone fragments, and gorily detailed hand-drawn illustrations of cadaver dissections are not often the stuff of an Artscape review, but then again the show now running through June 15 at the National Museum of Nature and Science in Ueno is no typical art exhibition. It traces the evolution of medicine as practiced in Japan since the Edo period (1603-1867), when the country's first human autopsies were performed and the translation into Japanese of a Dutch anatomical text triggered intense interest in the study of Western sciences.

|

| Mitsukuni Defying the Skeleton Specter Invoked by Princess Takiyasha by ukiyo-e master Utagawa Kuniyoshi is a celebrated 1845 triptych of a 10th-century legend. Its portrayal of a human skeleton in precise and eye-popping detail drew upon anatomical studies that had become widely popular in Edo as knowledge of the new science spread. |

Some museumgoers will be hard put to catch the curators' message, as the promotional materials and display captions are presented only in Japanese. Entitled I wa jin-jutsu (Medicine: The Healer's Art), the exhibition takes as it keyword the Confucian ideal of ren (or jin as it's pronounced in Japanese). Written with an ideograph that shows man linked with heaven and earth, it means virtue, benevolence, reverence for life. Confucius himself explained it quite simply: "to love others." So this is a show about "humanistic medicine," or what is also known as integrative medicine -- the art of treating the whole person, with an appropriate mix of conventional and alternative approaches. The claim is that Japanese physicians have been exceptionally primed for this as far back as the Edo days, thanks to their service-oriented mindset, their familiarity with Chinese herbal, bodywork, and acupuncture therapies, and their readiness to absorb and adapt Western knowledge. In Edo, this last element came through interactions with the Dutch, the only window on the Western world allowed by the shogunate authorities.

It might be a good thing that none of the captions are provided in English, as the show's subtext, like many of late, falls decidedly into the "we the unique Japanese" category. Certainly notions of virtuous service and rigorous study in the practice of medicine are nothing new or limited to this part of the world -- there is a long lineage of such values transmitted across generations since the days when the ancient Greeks worshipped Asclepius, the god of medicine and healing. His rod, entwined with a serpent signifying rebirth, remains a symbol of the field today. And the principles of compassion, altruism, and service are of course central to the Hippocratic oath.

|

| 3-D printers are now used in tandem with multi-slice CT scanners to generate real-time, patient-specific models, such as of healthy lungs (right) and those with a malignant tumor (left), thus enabling a non-invasive approach to surgical planning and training. Photo by Jeff Amas |

|

|

|

|

|

This illustration by Yamawaki Toyo is one of a set based on the autopsy he conducted in 1754 -- Japan's first. Though rudimentary, his drawings became a template for later studies. Medical collection, National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo

|

But no matter -- our planet is a better place whenever and however deeds for the greater good are recognized, practiced, and advanced. Even so, and language barriers aside, one hopes that Japan will increasingly come to share its strengths and viewpoints with the world because it makes sense to do so, rather than use them as rallying points to set the country apart.

That said, the historical materials on exhibit are remarkable for their scope and quality. Diagrams by Yamawaki Toyo (1705-62), who conducted Japan's first legally sanctioned dissection in 1754, and handwritten texts and scrolls by Sugita Genpaku (1733-1817) and Katsuragawa Hoshu (1751-1809), who compiled the first Japanese translation of a Dutch text on anatomy in 1774, are shown here in public for the first time. These seminal works launched the practice of modern medicine in Japan. Rare medical references such as a 1543 textbook by Andreas Vesalius (the founder of modern anatomy) and a 1627 edition of a surgical treatise by Ambroise Paré (surgeon to four French kings) underscore just how much serious study was taking place. Since the shogunate initially allowed access only to Western books that addressed nautical and medical matters, the bilingual medical dictionaries on display, which transferred literal reams of knowledge to Japanese doctors and everyday citizens alike, are among the oldest such technical references ever produced. Even the galley proofs, heavily marked in red, for a revised edition of the world's first English-Japanese dictionary are here -- thrilling stuff for word mavens involved with Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

While it is not part of the exhibition, this late 18th-century painting by Shiba Kokan depicting a meeting of China, Japan, and the West says volumes about the debates and tensions that arose in Edo-era Japan as scholarly pursuits shifted from traditional herbal medicine to Western sciences. Note the open page of the Dutchman's anatomical text vis-à-vis the rolled-up scroll of the Confucian scholar. |

Those familiar with local popular culture will recognize that the exhibition takes as its visual conceit the television drama Jin. (There's that keyword again.) Based on a manga written and illustrated by Motoka Murakami over a ten-year period from 2000, it aired in Japan and Korea after 2009. A kind of sci-fi historical fiction, it tells the tale of a modern-day brain surgeon who travels back in time to the Edo period, where he sets up a small clinic and saves patients with his advanced medical skills. The museum show transports us, like that misplaced surgeon, back to a time when encounters between China, Japan, and Europe unfolded in epic ways that greatly impacted scholarly, commercial, and interpersonal exchange in those cultures. At the same time, our insertion into the past brings present-day attitudes and wisdom into relief, showing us how we've gotten here and how far we've come.

|

| A grisly series of drawings from the late 18th or early 19th century shows the autopsy of an executed prisoner -- complete with a study of what happens to the lungs when air is blown in -- as a chronicler busily sketches the proceedings. Photos by Susan Rogers Chikuba |

|

|

|

|

|

The first models for studying meridian lines and acupuncture points are said to have been brought to Japan from China in 1378; by the Edo period both acupuncture and moxibustion were well established. Photo by Jeff Amas

All credited images are by permission of the National Museum of Nature and Science. Where no credit is given, the image is taken from the public domain.

|

While the archival material is plentiful and amazing -- and gruesome in parts -- the show does not deposit us in feudal Japan and leave us there. Exhibits from the Meiji period (1868-1912) recount how the country's early scholars of modern science, and their protégés, continued to build on the knowledge acquired during Japan's period of isolation, going on to found medical schools and programs of study. The last section presents recent achievements, such as models of diseased and healthy lungs, hearts, and brains constructed by 3-D printing, and a nifty demonstration of an endoscope (an instrument for which Japan holds 98% of the world market share). You can also see, with the aid of a microscope, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) -- a discovery for which two researchers, British and Japanese, shared the 2012 Nobel Prize.

With its own labs and clinics now breaking new ground in medical research and applications, Japan has come a long way from the days of watercolor studies on rice paper. But still, it's good to know that healing arts like acupuncture and moxibustion, which date back to this country's sixth-century exchange with China, continue to thrive and remain available to us today in every neighborhood throughout the country.

|

|

Susan Rogers Chikuba

Susan Rogers Chikuba, a Tokyo-based writer, editor and translator, has been following popular culture, architecture and design in Japan for 25 years. She covers the country's travel, real estate, hospitality and culinary scenes for domestic and international publications. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|