|

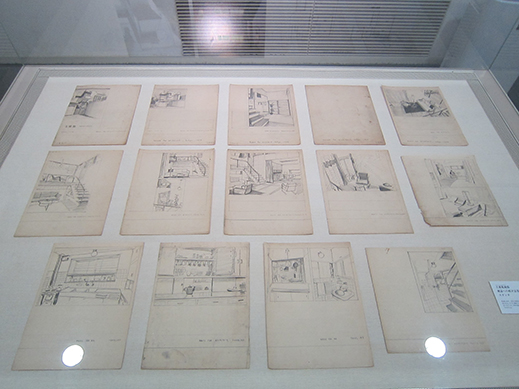

| Construction sketches and drawings by Kameki and Nobuko Tsuchiura displayed at a low angle behind glass vitrines. |

To commemorate the 20th anniversary of its opening, Tatemono-en, the open-air architectural museum located in Koganei Park, west of downtown Tokyo, is holding a special exhibition. A Dream of Modern Architecture: The Work of Kameki and Nobuko Tsuchiura gives visitors a glimpse into the life of what was perhaps Japan's first husband-wife architectural partnership. The show celebrates this trailblazing couple who dared to travel abroad in the early part of the 20th century and bring back to Japan profound influences from some of modernism's biggest heavyweights.

|

| Elevation for Kameki Tsuchiura's university thesis project, a church in deep relief that suggests early Wrightian influences. |

Kameki Tsuchiura (1897-1996) was still a student at the Imperial University (now the University of Tokyo) department of architecture when he first met Frank Lloyd Wright. The introduction was through Arata Endo, then a young architect, Wright enthusiast, and alumnus of the school from which he handpicked many of Wright's Japanese draftsmen, including Tsuchiura. Kameki and his new wife Nobuko (1900-98), who was also trained as an architect, began working for Wright on the Imperial Hotel in 1921. The next year Wright returned to the U.S. and the young couple soon followed. They worked as draftsmen for Wright for two years, both in Los Angeles and at Taliesin in Wisconsin. Together they completed drawings for a number of projects.

|

| Comfortable-looking tubular lounge chairs are more referential to the furniture of Thonet and Aalto than that of the couple's mentor Frank Lloyd Wright. |

The exhibition focuses primarily on the couple's residential projects completed after returning to Japan in 1926. Sketches and construction drawings are the main media on display. Regrettably these are mounted horizontally at a low angle behind glass vitrines, making the details a bit hard to read. While Wright's influence can be seen in nearly all of their work, the Tsuchiuras gradually moved away from the rigidity of Wright's style toward the new International Style influences coming from Europe. They replaced the block masonry with plaster panels on wooden frames, and endeavored to improve Japanese housing in general through the economy of means that comes with standardization in materials and layout.

|

| A custom vanity and stool designed and used by Nobuko herself, 1935. |

The centerpiece of the exhibit is a room-sized model, 1:5 scale, of the Tsuchiuras' best known work, their own home, completed in 1935. One facade of the model is cut away, revealing the architects' mastery of interlocking interior spaces in a way that a smaller model would not allow. From its outward appearance as a massing of white stacked volumes, it may be considered high-International Style modernism, but any student of Wright's work would recognize his influence in the deep eaves, the large window-wall, and the double-height central living space. Wright himself may not have been so complimentary. He expressed disappointment in the Tsuchiuras' embrace of the new movement, writing in a private letter, "[You have] gone over - with [Richard] Neutra - to the gas pipe rail and damper style . . . I am sorry to see the poverty of imagination in you . . ." (from a 1931 letter in the FLWA collection, in Anthony Alofsin, ed., Frank Lloyd Wright: Europe and Beyond, p. 224). The actual house, located in the Meguro district of Tokyo, is still well-preserved today thanks to the stewardship of its current owner. It was designated an Important Cultural Property of Tokyo in 1995.

|

|

| Kameki Tsuchiura's loose perspective sketches on display. |

By the mid-1930s the Tsuchiuras' practice was well established. They had completed over 20 projects, mostly homes. Kameki went on to other notable commissions such as the International Hall of Tourism in 1954 and Saitama Medical College in 1969. For her part, Nobuko became something of a celebrity; she appeared in lifestyle publications promoting their approach to interior design for the modern homemaker. A number of the magazines that survived over the years are on display, evoking the mid-century zeitgeist. Visitors to this exhibition may get the slightest hint that perhaps Nobuko was the more talented, more intuitive designer of the duo. Whether or not there is any truth to that, she clearly contributed a sensitivity and thoughtfulness toward the occupants of their buildings.

|

| A 1:5 scale model of the Tsuchiuras' own home in Tokyo, made especially for the exhibit. An example of the International Style, it was designated an Important Cultural Property in 1995 and still stands today. |

Like their contemporaries, the Tsuchiuras were experimenting with furniture design. Two upholstered reclining chairs and a vanity and footstool are on display. The pieces employ the tubular steel that was coming into vogue at the time, but are more referential to the turn-of-the-century bentwood forms of Thonet and Alvar Aalto's Paimio chair (circa 1931). The Tsuchiura furniture also seems to be much more comfortable and usable than any of the furniture their former mentor Frank Lloyd Wright had designed.

|

|

|

|

|

Self-portrait in oil, by Nobuko Tsuchiura.

All photos by Nicolai Kruger, by permission of the Edo-Tokyo Open Air Architectural Museum.

|

Today Nobuko Tsuchiura is widely recognized as Japan's first female architect, but whether she realized that at the time is unclear. The accompanying exhibition text for A Dream of Modern Architecture does not give any indication of the challenges Nobuko most certainly faced as a woman in her field. There have been some legendary slights for women in architecture, as when Charlotte Perriand, the revered French architect and furniture designer, turned up at Le Corbusier's atelier for an interview in 1927. He famously bid her adieu with a "We don't embroider cushions here." Through her persistence, she was later invited back and they had a long series of collaborations, but it took decades for Perriand to get equal recognition. A more contemporary example is Denise Scott Brown, who is still waiting to be credited retroactively for the 1991 Pritzker Prize that even her husband and lifelong collaborator Robert Venturi insists she deserves to share with him. Perhaps, considering the times, Nobuko Tsuchiura simply accepted that her credibility as a designer heavily hinged on the presence of her husband. As is often the case with husband-wife creative collaborators, their lives and oeuvres are so intertwined that we may never know where the ideas of one stopped and the other started.

|

|

Nicolai Kruger, AIA

Nicolai Kruger is an architect managing international projects at Pelli Clarke Pelli Architects, Japan. She has been living in Tokyo since 2006. She received her BFA in Design at Cornish College of the Arts in Seattle, followed by her Masters of Architecture at the University of Oregon. Her principal areas of interest include mixed-use, temporary structures, exhibition and lighting design. |

|

|