|

|

|

HOME > FOCUS > Nihonga on the Rocks: The Tenshin Memorial Museum of Art, Ibaraki |

|

|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese residents of Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Nihonga on the Rocks: The Tenshin Memorial Museum of Art, Ibaraki

Alice Gordenker |

|

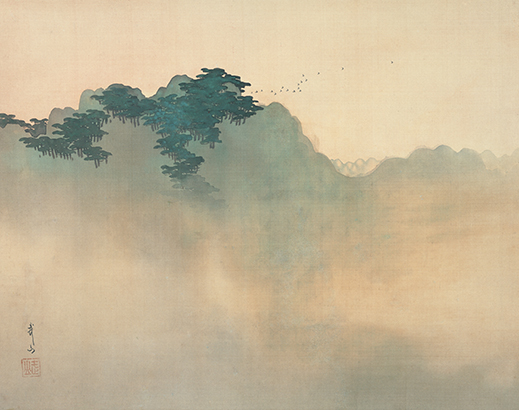

Toshio Matsuo (1926-2016), The Sound of Waves at Izura (1991), pair of six-fold screens, color on paper. Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, Ibaraki. |

At the edge of a wild and rocky sea coast in northern Ibaraki Prefecture, there is a museum dedicated to a man credited with revolutionizing Japanese painting -- even though he himself did not paint. As unlikely as that sounds, the homage is justified. Kakuzo Okakura -- best known in the West as the author of The Book of Tea -- brought to this remote location a tiny group of Japan's most promising painters and inspired them to find new ways of expressing space and light that greatly enriched modern Japanese painting.

The Tenshin Memorial Museum of Art, Ibaraki, is located at Izura, a seaside hamlet near the border with Fukushima Prefecture. It opened in 1997 as a sister institution of the prefectural Museum of Modern Art, Ibaraki in nearby Mito. Izura's claim to fame is that, for a brief period at the beginning of the 20th century, Okakura lived and worked here, mentoring a handful of disciples including Taikan Yokoyama, Shunso Hishida, Kanzan Shimomura and Buzan Kimura. All four become key figures in the Nihonga movement, which sought to revitalize indigenous painting in the face of the rising influence of Western art.

|

|

|

|

Left, the entrance of the museum. Right, the Japanese-style study in Okakura's home at Izura, recreated inside the museum's Okakura Tenshin Memorial Room. Photos by Alice Gordenker. |

The museum, which takes its name from the pseudonym Okakura used when writing poetry, is one of several attractions that memorialize the ground-breaking work these artists did here together. Visitors to Izura can also see Okakura's home and the Rokkaku-do (Hexagonal Hall), a seaside pavilion he built for contemplation and tea ceremonies. The distinctive red structure was swept away in the tsunami of 2011 but rebuilt a year later with donations from all over the country. Today, it is very much the symbol of Izura and Okakura's time here.

Okakura was born in Yokohama in 1862, just after the port was opened in response to pressure from Western powers after hundreds of years of national isolation. At his father's wish, Okakura received a largely Western education and became proficient in English. In the course of his schooling Okakura met the American educator and art historian Ernest Fenollosa (1853-1908), who helped him develop a deep appreciation for Asian art and culture at a time when many Japanese regarded all things Western as superior. Later, when Okakura began working in the Ministry of Education, the two embarked on a program to save Japanese antiquities from destruction, including a comprehensive survey of the artworks held by temples and shrines. Okakura also promulgated a set of rules for the protection of antiquities, a forerunner of the current Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties.

|

|

|

|

Left, Kakuzo Okakura (1862-1913), also known as Tenshin Okakura, photographed around 1898; image courtesy of the Tenshin Memorial Museum of Art, Ibaraki. Right, the Rokkaku-do pavilion today; photo by Alice Gordenker. |

At the time, Japanese painting was widely regarded as flat and primitive compared to Western painting. The primary complaint was that it lacked the mechanisms used in Western art, including scientific perspective and chiaroscuro shading, that create dimension and variations in light. Convinced that Nihonga could never compete unless this perceived deficiency was overcome, Okakura challenged his students to find new ways of expressing air and light. Rather than borrow from the West, he urged them to look within the traditions of China and Japan, so that their solutions might be authentically Asian.

One approach the group tried was to do away with the strong outlines that previously characterized Japanese art. Instead, they used wash techniques to put down pigment in subtle ways so that colors or tones seemed to melt into one another without perceptible transitions, lines or edges. This was initially mocked by critics as morotai (blurred style) and largely rejected by the established salons. The group at Izura persevered with the unconventional style, making modifications and eventually winning acceptance. Hishida and Yokoyama, in particular, came to be recognized as masters of this highly atmospheric way of painting, and their works in this style are in the collections of top-notch museums around the world.

|

|

Buzan Kimura, Morning at Izura (c.1906-12). Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, Ibaraki. |

The four artists did other important work in Izura as well. Yokoyama, for example, painted one of his most famous works there, completing it in 1909. Floating Lanterns depicts three Indian women at the banks of the Ganges River, and was highly praised for its novel pastel palette and its fresh view of contemporary India.

|

|

|

|

|

Taikan Yokoyama, Floating Lanterns (1909), color on silk. Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, Ibaraki.

|

As fruitful as it was, the collaboration lasted less than two years, from late 1906 until June 1908, when Hishida had to return to Tokyo to receive treatment for illness. Okakura also departed, to direct a new department of Asian art at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and the rest of the group disbanded.

Okakura was a worldly man of many interests and talents, as is demonstrated by the range of exhibits in the Okakura Tenshin Memorial Room. The largest is a slightly scaled down model of a fishing boat he designed himself, incorporating features from both Japanese and Western shipbuilding. He was also a world-class eccentric who spent his last years at Izura fishing in an outlandish costume of sealskin cloak and Taoist headwear, a photograph of which is also on display. You can see tea-ceremony utensils used by Okakura as well as facsimiles of the handwritten manuscripts for the books and lectures he wrote in English. His most successful and influential work was The Book of Tea, which he wrote in 1906 to explain teaism and Japanese aesthetics to a Western audience.

The museum is accessible enough to foreign visitors that you could arrive with no prior knowledge and come away with a sense of who Okakura was and why his time in Izura was important. The exhibits are captioned only in Japanese, so be sure to pick up the free headsets at the information desk for a useful audio guide with channels in English, Chinese and Korean as well as Japanese.

|

|

Tetsuo Matsumoto, Glen at Glencoe, Scotland (1991), color on paper. Yamatane Corporation Collection. On view 15 July to 27 August 2017. |

In addition to the permanent exhibition, which can be viewed whenever the building is open, the museum holds six or seven special exhibitions a year, usually on a theme from modern or contemporary Japanese painting. Through 8 July you can just catch a show of 15 recent artists working in the Nihonga tradition, most of whom are still living and painting. From 15 July to 27 August there will be an exhibition of the works of Tetsuo Matsumoto (1943-2012), who is best known for his massive views of famous places around the world, including the Grand Canyon and the Taj Mahal, painted very much in the Nihonga tradition. And this fall, to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the museum's opening, there will be a special exhibition of dragons in Japanese painting. That show, which will include ceiling paintings like those seen in Buddhist temples, will run from 25 October to 26 November.

All images are by permission of the Museum of Modern Art, Ibaraki.

|

|

|

| Tenshin Memorial Museum of Art, Ibaraki |

2083 Tsubaki, Otsu-cho, Kita-Ibaraki City, Ibaraki Prefecture

Phone: 0293-46-5311

Hours: April-September, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and October-March, 9:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. (no entry after 4:30). Closed on Mondays except when Monday falls on a national holiday, in which case the museum is closed the following day.

Access: From Tokyo, take the Super Hitachi or Fresh Hitachi limited-express train on the JR Joban Line, boarding at Shinagawa, Tokyo or Ueno and riding about two hours to disembark at Isohara Station. A taxi to the museum from Isohara takes about 15 minutes. Or change to the local train and ride one more stop in the same direction to Otsuko Station, for a shorter taxi ride of about 5 minutes to the museum. |

|

|

|

|

Alice Gordenker

Alice Gordenker is a writer and translator based in Tokyo, where she has lived for more than 17 years. For over a decade, she penned the "So, What the Heck Is That?" column for The Japan Times, providing in-depth reports on everything from industrial safety to traditional talismans. She translates and consults for museums, and has a special interest in making Japanese museums more accessible for visitors from other countries. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|