|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese residents of Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Spreading the Word on Japanese Ink Painting

J.M. Hammond |

|

Yujian, Mountain Village in the Clearing Mist, hanging scroll, Important Cultural Property, Idemitsu Museum of Arts |

With over 15,000 items in its collection, the Idemitsu Museum of Arts in the Marunouchi district of Tokyo has been introducing the public to East Asian and Japanese art for just over half a century. Currently it is exploring the legacy of ink painting, or suiboku-ga, from its roots in ancient China -- a civilization in many ways considered the font of Asian culture -- through its many manifestations in Japan.

The Winds of Suiboku-ga: Hasegawa Tohaku and Sesshu uses the idea of winds, or fu, which in Japanese can also mean "style," to reveal the many faces of ink painting, and in doing so attempts to highlight the achievements of two masters of the artform -- Sesshu (1420-1506) and Hasegawa Tohaku (1539-1610).

Sesshu, the earlier of the two artists, was born during the Muromachi period (1338-1573), when suiboku-ga flourished in Japan. Trained as a Zen priest, he had access to the Chinese ink paintings then housed in Japanese temples -- many of those considered the best having been produced by priests and monks of the Southern Song period (1127-1279).

Sesshu was particularly attracted to the work of Yujian, whose Mountain Village in the Clearing Mist is included here. The splashed-ink technique used in the painting would have been well known to Sesshu, and was emulated by artists in Japan, where it was known as haboku. As its name implies, the technique involves the artist, often with the assistance of a few glasses of fine sake, randomly splashing ink on paper. As the ink spreads, the resulting shapes and patterns may suggest mountains or other forms, which the artist can freely work on. Next to Yujian's work is an equally dynamic example by Sesshu himself, simply titled Haboku Landscape.

|

|

Sesshu (painting), Keijo Shurin (calligraphy), Haboku (Splashed Ink) Landscape, hanging scroll, Idemitsu Museum of Arts |

The links between Sesshu and some other works is less obvious, including a small unattributed painting utilizing fine, precise lines to depict an oxcart. Sesshu himself painted works in this style too, but unfortunately none of them are included in the exhibition. Also of note is a dramatic scene by Tani Buncho of fishermen in a boat caught in a heavy storm. This powerful work is included primarily because it is painted in a style that Sesshu would have been familiar with, and this gives us a glimpse into the artistic environment he was working in.

Sesshu had the rare opportunity to travel to China around 1468 or 1469, staying there for three years. However, his trip did not unearth the cornucopia of art that he was perhaps expecting. Compared to the art produced during his beloved Southern Song period, Ming Dynasty China was a different era with different preoccupations. Works by the priests and monks that were so treasured in Japan were a secondary concern to "literati" painting -- ink paintings made mainly by highly educated retired bureaucrats who were also amateur scholars.

Although disappointed, Sesshu nonetheless seems to have learned from his time in China, and this exhibition attempts to put his discoveries into some kind of context. Compared to his splashed-ink painting, two screens attributed to Sesshu's hand after his return from China reveal a style that could be considered more realistic than evocative. In Birds and Flowers of the Four Seasons (no longer on exhibit in July), Sesshu marshals a few strong, unperturbed lines to portray the strength of bamboo and some scratchy spikes to convey the jagged branches of pine trees. Using colored ink -- particularly leafy green and delicate pink -- in addition to the usual black, this screen is believed to reveal something of the artistic currents Sesshu would have been exposed to in China.

The only serious criticism is that these are basically the only works by Sesshu on display, which may be a disappointment for anyone lured in by his name in the title of the exhibition.

|

|

|

|

|

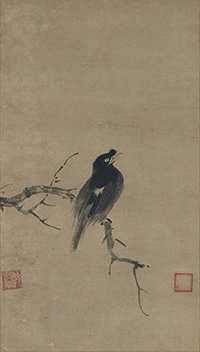

Muxi, Papa Bird, hanging scroll, Idemitsu Museum of Arts

|

The same can also be said for Hasegawa Tohaku, who makes his appearance in the next room. There are only two Tohaku works on display, but they are among his finest. Tohaku also called himself Sesshu V, claiming a direct lineage through five generations of teachers back to the master himself. He was also greatly influenced by the Chinese artist Muxi, who was a favorite of the Muromachi shoguns. So enamored with Muxi's work were the shoguns that they bought up as much of it as they possibly could, and when they could not get their hands on any more, they commissioned Japanese artists to paint in his style. On display here is one of Muxi's renditions of a type of bird called the papa, painted in bold, rough strokes of black.

Tohaku perfected Muxi's technique of contrasting different densities of ink to create atmospheric space, as demonstrated in his masterful Cranes and Bamboo (no longer on display in July).

Tohaku refused to paint what he had not seen with his own eyes. As papa birds could only be seen in China, and most Japanese artists, including himself, had never been there, he criticized them for their endless copies of a subject they had no firsthand knowledge of. When Tohaku tackled a composition requiring a black bird he painted one he was more familiar with, such as a crow, as can be seen in Crows on Pine and Egrets on Willow, where it contrasts well with the white of its companion.

|

|

|

|

Hasegawa Tohaku, Crows on Pine and Egrets on Willow, pair of six-fold screens, Idemitsu Museum of Arts |

The bane of Tohaku's life was the Kano school of painters, which passed on its techniques, and powerful connections, down through the generations, and blocked Tohaku's attempts to get important commissions from the shogun. Tohaku, however, finally got his day in the sun when the last truly talented member of the Kano family passed away. Some Kano school works are included in the last room in the exhibition, which looks at how ink painting in Japan fanned out to follow many different avenues of enquiry up until the Edo period (1603-1867).

By this time, Japan had belatedly learned to appreciate the kind of literati work that had long been popular in China, and one area of endeavor this section looks at briefly is Japanese practitioners of this tradition, such as the great Ike no Taiga, and Gyokudo, with his dry, scratchy style.

In total, The Winds of Suiboku-ga may be a little thin on works by the two artists it cites by name, but makes up for it by covering a wide, and perhaps surprising, breadth of ink painting styles.

All images are courtesy of the Idemitsu Museum of Arts.

|

|

|

J.M. Hammond

J.M. Hammond researches modernity in Japanese art, photography and cinema, and teaches in Tokyo, including as a faculty lecturer in the English department at Meiji Gakuin University. He has written about art for The Japan Times for over a decade. His essays include "A Sensitivity to Things: Mono No Aware in Late Spring and Equinox Flower" in Ozu International: Essays on the Global Influences of a Japanese Auteur (Bloomsbury, 2015) and "The Collapse of Memory: Tracing Reflexivity in the Work of Daido Moriyama" for The Reflexive Photographer (Museums Etc, 2013) [reprinted in the same publisher's 10 Must Reads: Contemporary Photography (2016)]. He has given various conference papers, including at the University of Hong Kong and the University of Oxford. |

|

|

|