|

|

|

HOME > FOCUS > Bursts of Color, Shades of Black: Nihonga at the Yamatane Museum |

|

|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese residents of Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Bursts of Color, Shades of Black: Nihonga at the Yamatane Museum

J.M. Hammond |

|

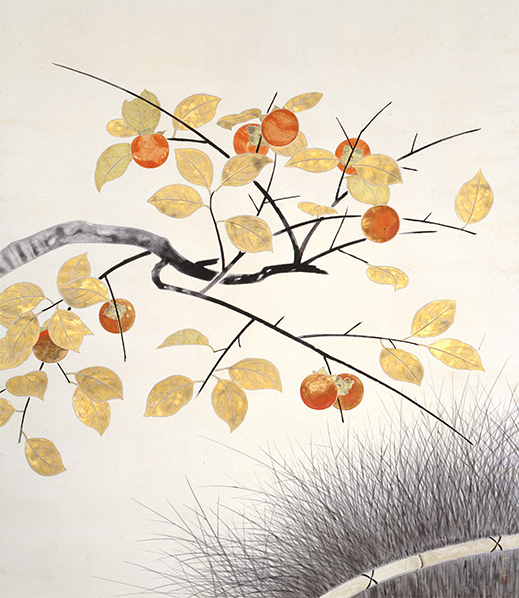

Kokei Kobayashi, Fruit, color on silk, 1936

|

Color helps us navigate and understand our world. Colors, of course, can take on different meanings, and importance, in different cultures. That much we all know, but we far too often assume that the way people perceive and classify color is relatively stable across cultures. Actually, how color is conceived can vary in subtle ways, and, in one culture, can be classified in subtle shades unfamiliar elsewhere. One example is how what is known elsewhere as "green" has traditionally been considered, in Japan, a shade of blue rather than an independent color. For instance, the traffic light in the color we normally call green is called "blue" here.

An exhibition currently on view in Tokyo, Reading Nihonga Through Color -- Kaii's Blue and Genso's Red, illustrates this ambivalence with the first work on display. In an otherwise naturalistically rendered landscape, a hillside that we would usually expect to see depicted in green is tinged with a subdued blue. In this show, the Yamatane Museum of Art uses the theme of color to explore some select pieces from its collection, which is based around Nihonga. This relatively modern style of painting utilizes several aspects of traditional Japanese art, but came into being in the 19th century as an attempt to clarify what the country's art is, or could be, in the modern era as Western art began flooding into Japan. As opposed to painting on canvas with oils, Nihonga artists use natural pigments to paint on paper, or sometimes silk.

|

|

Genso Okuda, Oirase Ravine: Autumn, color on paper, 1983 |

The painting with the blue tree-covered hillside is Autumn Colors from 1986 by Kaii Higashiyama (1908-99). Appropriate for an exhibition running from November until just before Christmas, this image of seasonal foliage opens the show. Autumn Colors is a classic example of "less is more," depicting a few branches of yellow leaves on the left with a cluster of red on the right, both standing out against the blue hill.

Higashiyama is one of the most prominent artists of the Nihonga style, and his name appears in the exhibition's title in relation to his vibrant use of blue. It is to blue that the show soon turns for a more detailed look. After establishing the seasonal theme with Higashiyama's work, we are taken off to summer, with a portrayal of Japan's most symbolic mountain peak in a glorious blue. Mount Fuji in Summer was painted by Kansetsu Hashimoto (1883-1945), at one time a pupil of Seiho Takeuchi (1864-1942), a renowned artist represented later in the exhibition.

Then we are thrust into winter, with the wonderfully evocative End of the Year, painted once again by Higashiyama. This work takes a bird's-eye view of Kyoto from the artist's hotel room, looking over the tiled rooftops of the city's machiya (wooden townhouses). The scene is suffused with an all-encompassing blue cast and dotted with tiny drops of white snow, heightening the winter atmosphere. The blue would seem to owe as much to the winter evening light as to the actual color of the roof tiles, which, in Japan's ancient capital, are predominantly gray.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kaii Higashiyama, End of the Year, color on paper, 1968

|

|

Kaii Higashiyama, Pervasive Verdure, color on paper, 1976 |

Higashiyama, however, is also known for his use of vibrant greens, as highlighted by two particular works in the section devoted to this color. One of these, Pervasive Verdure, takes an aerial view similar to that of the Kyoto scene, this time looking down on an expanse of trees. One charm of the work is the way the reflections of the trees cast patterns on the blueish water below. Nearby, another work by Higashiyama, Rising Moon, offers an even stronger juxtaposition between dark and light trees, complemented by the inclusion of a pale moon presiding above them.

Aside from the works on display, Reading Nihonga Through Color also scores points for introducing visitors to the pigments and techniques used by Nihonga artists. Through materials on exhibit, detailed captions and a video explanation, the show describes how the same pigment (for example, azurite for blue, or malachite for green) can provide a rich deep color when coarsely ground and lighter tones when finely pulverized, resulting in five or six different hues from a single basic color pigment. Further variations can be created by heating certain pigments to darken them through oxidization.

The way an artist applies the paint also determines the quality of color -- the same pigment applied in multiple layers will provide a more opaque solidity than it would when applied just a few times. Altogether, these and other techniques allow Nihonga artists to create a range of hues and color tones from a fairly limited selection of base pigments.

|

|

Kokei Kobayashi, Autumn Fruit, color on paper, 1934

|

The other half of the exhibition's title refers to the vivid reds favored by Genso Okuda (1912-2003), who associated the color with life itself. One of his paintings provides the highlight of the next room, the impressive Oirase Ravine: Autumn, which is approximately five meters wide and explodes in rich vermilion and other shades of red. A display case holds some glass jars from the artist's studio containing pigments he used -- notably cinnabar, which he ground coarsely for the deep reds and pulverized more finely for yellow hues. The huge size of Oirase Ravine: Autumn can be attributed to the artist's wish, as he approached the end of his life, to leave behind some works of substance: after turning 70, he embarked on a series of large-scale pieces.

Red and blue are pitched as the most striking, perhaps even the most representative, colors of Nihonga, but there are several others that should not be overlooked. Yellow is a fairly minor player, but several works in this color are nonetheless featured here, including Seiho Takeuchi's Ducklings. More pertinently, black and gold have always played a strong role in Nihonga, and Japanese art generally, and these two colors are given particular attention in the exhibition.

The most common form of black pigment has long been sumi, made from charcoal combined with glue, but pinewood and plants such as rapeseed have also yielded their own shades of black. Another master of the Nihonga style, Gaho Hashimoto (1835-1908), is showcased here with Hawk on a Rock, in which he coaxes an impressive spectrum of tones out of his black pigments, from dark swathes of ink for the dense parts of the bird's body to lighter shades for the detail of individual feathers.

|

|

Togyu Okumura, Maiko, Apprentice Geisha, color on silk, 1954 |

In Maiko, Apprentice Geisha by Togyu Okumura (1889-1990), the young geisha's deep black kimono serves as a foil for her luminous white skin and imbues her with an air of refinement. In the lower part of the kimono, gold leaf is lightly sprinkled for added effect. Gold paints (kindei) have also been used by Japanese artists. Kokei Kobayashi (1883-1957) applies two different types in Autumn Fruit, on display in the section on gold. These are used to show variations in color between the top and underside of persimmon leaves, as well as their changing hues as they wither in the approach to winter.

Nude by Matazo Kayama (1927-2004), with its aroma of eroticism and lavish gold backdrop, has a vaguely Gustav Klimt feel to it -- which is fitting since, at one point in his career, Kayama began studying in detail many of the techniques of the Rinpa style that inspired Klimt. He displays his mastery of these traditional techniques in the section on silver in Screen with Floral Fans, where he uses silver leaf, giving the work the air of a classical-period piece, and applies strips of gold foil to create undulating patterns. Yet in Waves, in the section on white, he shows his interest in experimenting with new techniques and equipment such as the airbrush -- and even a vibrating atomizer -- to produce the crashing, splashing dynamism of the white spray of waves crashing against rocks.

In this way, Reading Nihonga Through Color demonstrates not only how Japanese artists have used traditional pigments and techniques but how they have experimented with new approaches to achieve fresh effects. With about 50 works in all, it is not a huge exhibition but provides a compact few hours of enjoyment, particularly for visitors interested in exploring the colors of Japanese art.

All images are courtesy of the Yamatane Museum of Art; all works shown are from the collection of the museum. |

|

|

J.M. Hammond

J.M. Hammond researches modernity in Japanese art, photography and cinema, and teaches in Tokyo, including as a faculty lecturer in the English department at Meiji Gakuin University and at Gakushuin University. He has written about art for The Japan Times for over a decade. His essays include "A Sensitivity to Things: Mono No Aware in Late Spring and Equinox Flower" in Ozu International: Essays on the Global Influences of a Japanese Auteur (Bloomsbury, 2015) and "The Collapse of Memory: Tracing Reflexivity in the Work of Daido Moriyama" for The Reflexive Photographer (Museums Etc, 2013) [reprinted in the same publisher's 10 Must Reads: Contemporary Photography (2016)]. He has given various conference papers, including at the University of Hong Kong and the University of Oxford. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|