|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese residents of Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Altars to the Ephemeral: Shin Ikeda's Alchemy of the Everyday

Colin Smith |

|

Chandelier III, 2018, enemas, chains, light bulbs, electrical cords. Collection of the artist |

Decoration "Donbei", 2012, embroidery on paper. Collection of the artist. Photo by Colin Smith |

What do embroidery, lacework, and sewing have in common with monumental steel sculpture and performance art involving self-inflicted bodily harm? Answer: with notable exceptions, we associate these practices with a certain gender. Does it matter that Shin Ikeda, whose technically exquisite, moving and hilarious work involves the former group of skills, is male? It shouldn't, though it undeniably adds a further wow factor to the 45-year-old artist's mastery of embroidery, as does the fact that he only took it up in his thirties.

|

Life With Color "Cup Noodles", 2010, embroidery on noodle cup. Courtesy of Studio J. Photo by Colin Smith

|

|

Passport II, 2019, embroidery on washbowl. Collection of the artist. Photo by Colin Smith |

Born, educated, and currently based in Osaka, Ikeda works in several different modes, all of which show fascination with mundane, disposable objects and dedication to meticulous hand-crafting. The current exhibition at Nishiwaki Okanoyama Museum of Art, in the center of Hyogo Prefecture (and the exact geographic center of the country -- the museum is in a park marking Nihon no Heso, the "navel of Japan"!) is in three mimetically titled sections focusing on these modes. Section I, "Chikuchiku" (prickly), primarily features embroidery works in which mass-produced items -- an instant udon-noodle lid, a paperback with a bookstore's generic brown-paper cover, a plastic washbasin from the public bath -- are either faithfully embroidered over, coloring inside the lines as it were, or embellished with incongruous emblems and designs such as a paulownia crest or traditional textile pattern, or both. Life With Color: Cup Noodle is embroidered on the inside of the familiar polystyrene cup so loose threads hang willy-nilly off the exterior, a behind-the-scenes look at the patient work that went into it, as are a blank Japan Post postcard and a supermarket shopping bag. The altars in the Excessive Packaging series each feature an enema container in its unfolded, gold-coated package in what manages to be a touching and not at all snicker-inducing enshrinement of the cast-off object.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Excessive Packaging "Kotobuki Enema 10g", 2019, paper, enema. Collection of the artist

|

|

Switch, 2014, light bulb, electrical cord, switch. Collection of the artist

|

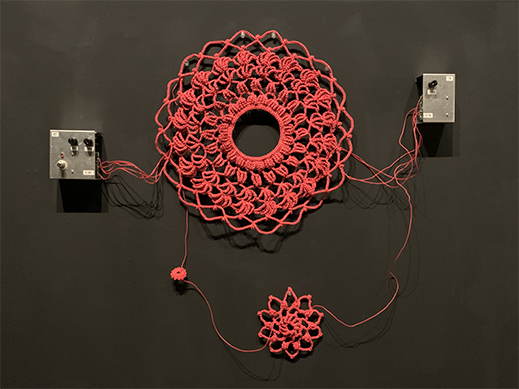

In section II, "Pikapika" (twinkling), the gallery is painted black and lights dimmed to showcase a centerpiece of the show, Chandelier III -- a delicate, enchanting construction of chains and translucent baby-pink enema containers -- and the Switch series, in which the artist took nearly kilometer-long electrical cords and wove them into large, intricate doily-like circles, each connected to a power source and illuminating a small light bulb. Here Ikeda interweaves his two concerns, exaltation of the neglected (nothing's more disposable than an enema, or more unjustly taken for granted than electricity) and mind-bogglingly intricate manual labor, such as women were obliged to do pre-Industrial Revolution and many people now do as a hobby, which alchemically transforms the mundane to the sublime. The artist has said that when he creates a work, he begins by "trying to make the most useless thing possible" -- a wry statement, considering all Fine Art is intrinsically "useless." Museum curator Midori Hasegawa says there are plans to have Chandelier III, which Ikeda believes would best be viewed in a restroom, installed there along with a replica of Marcel Duchamp's iconoclastic readymade urinal Fountain. Ironically, this could render both works more "useful" than originally intended.

|

|

Fluffy Colt Government, 2015-, felt, thread, cotton. Collection of the artist |

The final section, "Fuwafuwa" (fluffy), is a departure from the others in its chaotic expansiveness. Playful, seemingly abstract forms, made of felt and other fabric in candy-pop colors, are suspended from the ceiling. They recall sprockets and pistons of some machine, but the title Fluffy Colt Government might not convey, as the Japanese wall text explains, that they are faithful, enlarged reproductions of parts of a Colt pistol nicknamed the "Government" because it was standard-issue for U.S. armed forces. Inspired in part by news of a young man arrested for using a 3D printer to produce a working gun, Ikeda speaks to youths' attraction to firearms with the childhood associations of soft fluffy toys and twirling mobiles, while dismantling, disarming, and rendering flaccid a symbol of violence-backed authority. Do we need the wall-mounted text explaining the work? Happily, unlike some conceptual works, we can enjoy it without realizing what it is, though knowing certainly adds layers of appreciation.

|

|

Circuit Effector, 2015, guitar effector and electrical cord. Collection of the artist. Photo by Colin Smith |

The museum itself is something to see. Designed by Pritzker Prize winner Arata Isozaki in the 1980s, it recalls the heady economic-bubble period with both its look -- a postmodern mix of classical elements with clean lines, unfinished concrete and glass block, and pastel hues -- and its very presence as a museum, exhibiting contemporary art in a smaller off-the-beaten-path city, that might not be built in our leaner times. The central atrium has pink and orange geometric walls, tile mosaics, glass-block floors, and a slim steel spiral staircase leading down to the adjoining Atelier, a civic gallery that is free of charge, as is the semi-detached, pyramid-roofed Meditation Room on the opposite side.

View from Idobashi Bridge over the Kakogawa River, 2016. The panorama at the center of Japan, from left: Nishiwaki Okanoyama Museum of Art, Nihon-Heso-Koen Station, and the Kakogawa River. Photo by Shuji Yamada |

Outside the museum is a large mural by Tadanori Yokoo, Nishiwaki's most famous native son. While in Nishiwaki, Yokoo fans will want to take a walking tour of sites depicted in his iconic Y-junctions series, a map of which is available downstairs at the museum and downloadable here (in Japanese). Hop on the train at Nihon-Heso-Koen Station next to the museum to get downtown and see them. Before doing so, cross under the tracks and visit the "Taisho navel of Japan," a mystical spot with stone monuments to what was considered Japan's geographical center for most of the 20th century. (On the hill behind the museum is the "Heisei navel," determined in the '90s with more precise GPS rather than triangulation, along with a charmingly retro kids' playland and a science museum -- recommended for families!)

|

|

|

|

|

Taisho Nihon no Heso ("Taisho-era Navel of Japan"), the geographical center of Japan as triangulated in the early 20th century. The site is less accurately pinpointed but more atmospheric than the nearby Heisei Nihon no Heso. Photo by Colin Smith

|

Yokoo grew up in a family of kimono fabric traders, and the region is famous for textiles, though this appears unrelated to the selection of embroidery wunderkind Ikeda for the third edition of Art no Tobira (Gateway to Art), the museum's ongoing series showcasing innovative and emerging artists. Curator Hasegawa remarks, "Ikeda's work is a perfect fit for the Art no Tobira series because it brings a bold, fresh sensibility to ephemeral items we usually overlook, and delivers discoveries and surprises that turn the everyday into art." Look at the objects around you: how many of them could be transformed by "the adventuresome spirit and wit we associate with poets" (Hasegawa on Ikeda) into modestly sized but transcendent works of gloriously "useless" art?

All works are by Shin Ikeda, images courtesy of Okanoyama Museum of Art Nishiwaki, except where otherwise noted. |

|

|

Colin Smith

Colin Smith is a translator and writer and a long-term resident of Osaka. His published writing includes the travel guide Getting Around Kyoto and Nara (Tuttle, 2015), and his translations, primarily on Japanese art, have appeared in From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (MoMA Primary Documents, 2012) and many museum and gallery publications in Japan. |

|

|

|