|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese residents of Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Designing the New: Modern Design in 20th-century Japan

J.M. Hammond |

|

Bruno Taut, Former Hyuga Villa, 1936. Photo: Sadamu Saito

|

Twentieth-century modernism in Japan is often considered something that the country imported wholesale. But the reality is not quite so straightforward, as Japan already exhibited much of the simple, elegant style that is the hallmark of modernism in the West, and the two, over time, became closely entwined.

A new exhibition at the Panasonic Shiodome Museum of Art in Tokyo looks at modernism in Japan from the 1930s through the 1960s, specifically in the field of interior design and furniture (and, to a limited extent, architecture). Dreams of Life Connected by Modern Design explores the connections, interactions and collaborations between designers in Japan and from overseas, and how Japan not only pursued its own take on modern design, but also made a contribution to international developments.

The exhibition opens with a look at Bruno Taut, the German architect and urban planner who is a key figure in the story of Japanese, and international, modernism -- although not necessarily in the stereotypical brutalist concrete monstrosity sense, as he was a long-term advocate of the garden city approach to town planning, which utilizes lots of greenery. Taut left Germany for Japan in 1933 after the Nazis took power. He was struck by the astounding simplicity and elegance of the Katsura Imperial Villa in Kyoto, which for him epitomized the aesthetic standards modern design should be striving toward. Taut stayed in Japan for three years, teaching craft art design and writing books on Japanese architecture and culture, introducing the West to Japanese visual sensibilities.

|

|

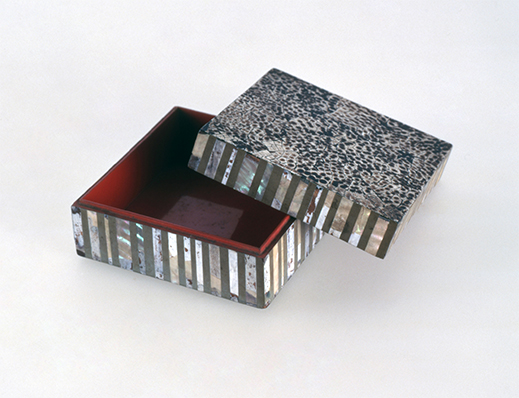

Bruno Taut, Square cigarette case with egg shell inlay, 1935. Gunma Prefectural Museum of History |

Taut designed a few buildings in Japan, but finding it difficult to get sufficient commissions, moved on to Turkey. The only building project designed by Taut still standing in Japan -- the basement of the Hyuga Villa in Atami -- is introduced in the exhibition, as well as various smaller objects, such as a cigarette case with egg shell inlay. While Taut was here he was introduced to the textile shop Miratiss, with outlets in Karuizawa and, later, Ginza in Tokyo, and he went on to design the interior, shop sign and wrapping paper for the store.

Over a decade before Taut arrived in Japan, however, the Czech-American architect Antonin Raymond and his wife Noémi (formerly Pernessin) had already made their home here. The exhibition includes photographs of the dome-like structure of the summer house and studio that they designed and built in Karuizawa. Antonin Raymond originally came to Japan as an assistant to Frank Lloyd Wright and helped with his construction of the second Imperial Hotel, although he did not stay with Wright for very long.

|

|

Antonin Raymond, New Studio in Karuizawa, 1963. Photo: Sadamu Saito |

During their various stays in Japan, and when back in America, the couple collaborated with many Japanese and Japanese-American designers. One of these was the sculptor Isamu Noguchi, with whom Antonin Raymond collaborated on the Reader's Digest Building in Tokyo after World War II. He had returned to the U.S. in 1939 with his wife, but came back to Japan in 1947 with fresh ideas and knowledge of new design techniques. Considering the publisher's reliance on international communications, Raymond designed the building so it was suitable for housing the complex telex systems of the day, and simplified the layout with the cumbersome wiring and cables placed under the floorboards.

Noguchi designed the garden for the building, one of several outdoor spaces he was charged with creating in Japan, another being the garden of Keio University, detailed in the exhibition. Displayed prominently are Noguchi's paper and wire-frame Akari lampshades. Designs similar to some of his lampshades are ubiquitous today, found everywhere from Ikea to high-end shops, and are often considered traditional Japanese lampshade designs, but actually owe a lot to Noguchi's original creations. They are based on outdoor lanterns that he encountered in Japan's Gifu Prefecture and gave a modern transformation for use indoors.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Isamu Noguchi, Akari Light Sculpture 33S (BB3 stand), 1952. Hida Earth Wisdom Center

|

|

Isamu Noguchi, Akari Light Sculpture 10A, 1952. Hida Earth Wisdom Center |

The designer Isamu Kenmochi coined the term "Japanese Modern" to describe the developments taking place in the country at this time. He was criticized from some quarters for pushing a kind of Japanese essentialism, but responded by arguing that he was simply promoting the idea of a "high-quality superior design of modern Japan" resulting from the combination of traditional techniques and modern production methods -- or sometimes straight-up old-fashioned craftsmanship. His rattan Round Chair, on display here, requires an artisan ten hours to make in one uninterrupted sitting, as otherwise it will lose its shape. Kenmochi may not be a household name, but some of his designs are easily recognizable to many -- ranging from this chair, which has a place in the Design Collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, to the shape of the little bottles of Yakult yogurt drink.

In Kenmochi's day it was common for the architect of a building to also design the interior and furniture, but he was asked by the legendary architect Kenzo Tange to take on this task for the Kagawa Prefectural Government Office, which is introduced through photographs in the exhibition. Tange himself contributed some of the furniture designs as well as the building itself, and asked the artist Gen'ichiro Inokuma to provide a huge work to hang on the wall, extending the collaboration into the field of fine arts to provide a warm welcoming atmosphere. Kenmochi, too, asked the artists Toko Shinoda and Matazo Kayama to contribute works when he designed the interior of the Keio Plaza Hotel in Shinjuku, Tokyo. Kenmochi was the design director of the Industrial Arts Institute in Japan, and heavily involved behind the scenes, before striking out with his own design practice in 1955. He worked tirelessly throughout his life to promote recognition of the designer, a role that was little understood or appreciated at the time.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Isamu Kenmochi, Kashiwado Chair T-7165, 1961. Matsudo City Board of Education

|

|

Isamu Kenmochi, Round Chair C-316, 1960/1972. Musashino Art University Museum & Library |

Because many "Japanese Modern" products are interior designs or otherwise related to architecture, they are represented here in large part by images of the items, historical photographs of the designers, and lots of panels, in both Japanese and English, explaining historical developments. So it is great that there are also numerous physical objects to look at, such as Noguchi's lamps and plenty of furniture. Among the highlights are some other chairs by Kenmochi, such as his immensely stylish fabric-covered Armchair FRP-7022C from 1967, and the unusual and solid-looking Kashiwado Chair from 1961.

A couple of chairs toward the end of the exhibition clearly bring home the point about traditional aesthetics meeting modern needs. One of these, Chair for Saint Paul's Catholic Church, was a product of the Raymond design firm, and physically put together by George Nakashima, a Japanese-American designer who studied architecture in the U.S. and France before working at the firm for five years from 1934. Across the chair's wooden frame is suspended a seat made of woven grass threads, a design that displays both traditional materials and a modern sensibility. Nakashima later concentrated his efforts on furniture and became affiliated with the Sanuki Minguren group, in the southern city of Takamatsu, who used traditional tools in their crafts. The exhibition successfully shows how what might be called Japanese Modern was not a complete break but in many ways a continuation and update of tradition.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Raymond Architectural Design Office, Chair for St. Paul's Catholic Church, ca. 1935. Sakura Seisakusho Inc.

|

|

George Nakashima, Conoid Chair, 1960/1992. Musashino Art University Museum & Library |

All images courtesy of the Panasonic Shiodome Museum of Art. |

|

|

J.M. Hammond

J.M. Hammond researches modernity in Japanese art, photography and cinema, and teaches in Tokyo, including as a faculty lecturer in the English department at Meiji Gakuin University and at Gakushuin University. He has written about art for The Japan Times for over a decade. His essays include "A Sensitivity to Things: Mono No Aware in Late Spring and Equinox Flower" in Ozu International: Essays on the Global Influences of a Japanese Auteur (Bloomsbury, 2015) and "The Collapse of Memory: Tracing Reflexivity in the Work of Daido Moriyama" for The Reflexive Photographer (Museums Etc, 2013) [reprinted in the same publisher's 10 Must Reads: Contemporary Photography (2016)]. He has given various conference papers, including at the University of Hong Kong and the University of Oxford. |

|

|

|