|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Rising Sons: The Bunriha Architecture Group

Christopher Stephens |

|

The six Bunriha members not long after the group was formed in 1920. Front row (left to right): Shigeru Yada, Mamoru Yamada, and Kikuji Ishimoto; back row: Keiichi Morita, Sutemi Horiguchi, and Mayumi Takizawa (photo courtesy of NTT Facilities). |

Just over a century ago, as the Spanish flu was raging across Japan, the Bunriha Kenchikukai emerged as the country's first architecture movement. The 100 Years of Bunriha: Can Architecture Be Art? exhibition (running through 7 March at the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto) traces the group's short but influential career through a wealth of documents, blueprints, photographs, models, and films.

The Viennese Secession, a diverse group of Austrian artists and architects who championed internationalism and opposed traditionalism in the arts, coalesced in 1897. Originally associated with Art Nouveau, the movement soon came to be seen as a harbinger of Modernism. Some 20 years later, in 1920, six architecture students at Tokyo Imperial University were inspired by the Austrian artists to start their own movement: the Bunriha Kenchikukai (Secessionist Architecture Group). The loose-knit group, consisting of Kikuji Ishimoto (1894-1963), Mayumi Takizawa (1896-1983), Sutemi Horiguchi (1895-1984), Keiichi Morita (1895-1983), Shigeru Yada (1896-1958), and Mamoru Yamada (1894-1966), remained active until 1928, concentrating primarily on exhibiting and publishing activities. Rather than displaying a unified style, each of the designers pursued his own vision, absorbing elements of Expressionism, Classicism, and Modernism.

As every movement must, Bunriha announced its arrival with a brief manifesto:

We rise up!

We secede from the architectural realm of the past to create a truly significant new realm with every building that we construct.

We rise up!

We strive to awaken all that is sleeping in the architectural realm of the past, and rescue all that is on the verge of drowning.

We rise up!

We joyously give our all to attain these ideals until we collapse or die. We unanimously make this declaration to the world.

While short on details, there is a familiar ring to the statement: out with the old, in with the new. For the Bunriha members, this meant distancing themselves from the imitative styles that had prevailed in Japan since the late 19th century, when the English architect Josiah Conder was hired by the Meiji government as the nation's first teacher of Western architecture techniques. The six young upstarts envisioned a democratic approach to design that was more in keeping with the openness of the Taisho period (1912-1926) while making their work a vehicle for self-expression.

|

|

Mayumi Takizawa's model of Mountain House, 1921 (reproduction made in 1986 under Takizawa's direction; private collection). |

Though trained in architecture, Bunriha displayed a preference for art. Modern sculpture, especially the work of Auguste Rodin, had a particularly strong impact on the group. Take, for example, Mayumi Takizawa's Mountain House (1921), a never-realized proposal that would fit nicely in a fairy tale. Looking more like a church or monastery than a house, it features a monumental staircase leading up to a round entryway topped with a pointed roof. Positioned around the mountain-like structure are six large windows hidden in deep recesses that recall the pleats of a skirt.

Bunriha first came to public attention in 1922 at the Tokyo Peace Exposition, a sprawling event held to commemorate the end of World War I some four years earlier. Among several pavilions and other structures designed by group members was Sutemi Horiguchi's Power and Machinery Hall, a huge red-roofed barrel vault with semicircular arches on the ends, and dozens of windows lining the sides.

|

|

A picture postcard of Sutemi Horiguchi's Power and Machinery Hall at the 1922 Tokyo Peace Exposition in Ueno Park (private collection).

|

The following year Horiguchi traveled to Europe to see recent architecture by the Bauhaus, which had opened in 1919, and the Amsterdam School, a style associated with Expressionist design and socialist principles. On his return to Japan, Horiguchi published a book on modern Dutch architecture, and created one of Bunriha's most attractive works, Shien-so. The house, built in Saitama in 1926, was clearly informed by residential designs in rural Holland, but it also incorporated a thatched roof, embodying Bunriha's interest in Japanese minka, the traditional dwellings of farmers, artisans, and merchants.

Sutemi Horiguchi's Shien-so, a 1926 house built out of plaster, clay, and brick for a kimono maker in Saitama, north of Tokyo (contained in Collected Illustrations of Shien-so, Tokyo City University Library).

|

At the same time, the Tokyo-based group was very much involved with that city. The Great Kanto Earthquake devastated Tokyo and much of the surrounding area when it struck just before noon on 1 September 1923. (Frank Lloyd Wright's Imperial Hotel, which had opened earlier that morning, managed to survive the disaster.) Among the vast number of post-quake building projects was an effort to restore 120 bridges. Mamoru Yamada and Bunzo Yamaguchi (one of three architects who later joined Bunriha) provided many of these designs, including that of Eitai Bridge (1926), the first reconstruction project to be completed. The gently curving structure, spanning the Sumida River in Chuo Ward, was lauded by the writer Ryunosuke Akutagawa at the time, and designated an Important Cultural Property in 2007.

Eitai Bridge (1926), designed by Mamoru Yamada and Bunzo Yamaguchi following the Great Kanto Earthquake (photo by Masao Horino, 1930-31, private collection).

|

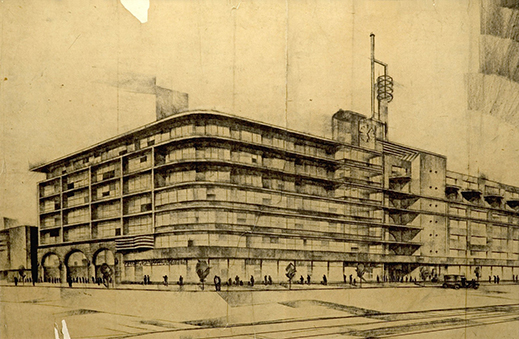

The 1928 design for the Nihonbashi branch of Shirokiya Department Store is another example of Bunriha's contribution to the urban landscape. Conceived by Yamaguchi and Kikuji Ishimoto, the project gave the designers, both of whom had been working at the Takenaka Corporation (one of Japan's largest general contractors), the chance to strike out on their own. The idea was to make something visually appealing on a small budget that could compete with stores in more upscale neighborhoods of the city. With rounded corners, expansive windows, and floor slabs that extended outward to accentuate the horizontal lines, the work has a warm and welcoming air. Unfortunately, the building is best remembered for the tragic fire that broke out in the store in 1932, only a year after it opened, leaving 14 people dead.

|

|

Perspective view of Kikuji Ishimoto and Bunzo Yamaguchi's 1928 design for the main branch of Shirokiya Department Store in Tokyo's Nihonbashi district (Ishimoto Architectural & Engineering Firm, Inc.). |

After going their separate ways in 1928, Bunriha's members enjoyed successful careers in their own right. Mamoru Yamada's works are perhaps the best known. These include the Nippon Budokan (located near the Imperial Palace in Tokyo), built to host the judo competition at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics before serving as a concert venue for the Beatles two years later. Yamada's other legacy is Kyoto Tower, also completed in 1964. This divisive landmark, seen by many as an aberration in the traditional city, remains Kyoto's tallest structure.

The road to Japan's emergence as one of the world's leading producers of cutting-edge architecture leads back to Bunriha, and this comprehensive introduction to the group's work is not to be missed.

All images provided by the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, unless otherwise noted.

|

|

|

Christopher Stephens

Christopher Stephens has lived in the Kansai region for over 25 years. In addition to appearing in numerous catalogues for museums and art events throughout Japan, his translations on art and architecture have accompanied exhibitions in Spain, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, South Korea, and the U.S. His recent published work includes From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (MoMA Primary Documents, 2012) and Gutai: Splendid Playground (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2013). |

|

|

|