|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Mind Travel to Jomon Times: A Trio of Archaeological Sites in Aomori

Susan Rogers Chikuba |

|

Goggle-eyed clay figurine, Korekawa-Nakai site, Aomori Prefecture, final Jomon period, Important Cultural Property. Photo © Korekawa Archaeological Institution

|

The northernmost prefecture on Japan's main island of Honshu, Aomori has some 3,000 Jomon-period archaeological sites -- even its capital city lays claim to a whopping 400. The prefecture is home to half of the 17 sites in northern Japan that are now under review for inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage list. In fall 2020 I visited three of these and their affiliated museums, as well as the excellent Aomori Prefectural Museum. There is a staggering body of material still coming from these excavations, which curators and other scholars continue to study and debate for insights into the Jomon: a prehistoric, pre-agricultural society that subsisted across Japan's islands for more than 12 millennia, and whose people created some striking art along the way.

|

|

Spouted vessel, Korekawa-Nakai site, Aomori Prefecture, final Jomon period, Important Cultural Property. Pottery shapes and their decorative styles became more elaborate toward the end of the Jomon period. A special exhibition on spouted vessels, believed to have been made for ceremonial purposes, is now showing at the Korekawa Archaeological Institution through 5 May. Photo © Korekawa Archaeological Institution

|

The Jomon period (13,000-400 BCE) is, roughly, the stretch of time between the Paleolithic age of stone tools and the beginnings of full-fledged rice cultivation on the Japanese archipelago. It is characterized by hunter-gatherer-fisher communities that had transitioned to sedentism, as suggested by the increased production of decorated pottery, personal ornaments, and ritual objects. The Jomon people of northern Japan had an abundant source of nuts in the deciduous forests, and used bows and arrows, spears, and game pits to hunt. At the Sannai Maruyama settlement in the present-day city of Aomori, goose, duck, pheasant, deer, rabbit, and wild boar meat were all on the menu. Gravesite studies show that the people who lived here kept dogs, and that these likely hunting companions were buried with signs of respect. Sannai Maruyama residents also fished the waters of Mutsu Bay and as far away as the Tsugaru Strait, using hooks, harpoons and nets. Clam, octopus, squid, and mantis shrimp remains have been found along with those of halibut, herring, shark, salmon, trout, amberjack, and cod.

|

|

Mounded-earth pit dwellings like this one at the Sannai Maruyama site are based on evidence drawn from excavations.

|

Sewing needles were made from the ribs and metacarpals of game; thighbones became spears. Fish hooks were rendered from antlers; hammers from the antler base. These early people harvested sea salt, too, collecting it in earthenware vessels, boiling it down, and drying it in the sun. Whether its production was for trade, to preserve foods, for ritual purposes, or a combination of the above is unknown. Boar-tusk ornaments found in Hokkaido, and obsidian implements found in Aomori, point to the trade that took place between communities of Hokkaido and northern Honshu. Items made of jade and amber and repaired with tar -- all materials that were not available locally -- indicate exchanges with far-flung places as well. Jade unearthed in Aomori has been traced to a quarry in Niigata, more than 700 kilometers to the south.

|

|

The Komakino stone circle is just 20 minutes by car from the Sannai Maruyama site. Together they make for a full day of exploration. Komakino may have been a ceremonial hub for a number of settlements in the area.

|

Here's a bit of global perspective. Around the time Paleolithic artists were decorating the Lascaux caves (17,000-15,000 BCE) in present-day France, potters were already firing earthenware at Odai Yamamoto, the oldest of the Jomon sites in Aomori. When the central megaliths of Stonehenge were raised in 2500 BCE, the settlements at Sannai Maruyama and Korekawa were in full swing -- as was Mohenjo-daro in the Indus Valley, one of the world's first major cities. The Komakino stone circle (2000 BCE) is 500 years younger than the Giza pyramid complex, and predates the Parthenon by about 1,500.

It's fascinating to walk these sites today, pore over their related exhibits, and wonder at the lifeways of these ancient people. They were among the first on the archipelago to fire pottery, and were already using lacquer and vibrant red ocher pigment at least 9,000 years ago. Beautifully carved wooden lacquerware of three millennia ago, found at the Korekawa site in what is now the city of Hachinohe, can be seen at the Korekawa Archaeological Institution. At Sannai Maruyama there is a stately road, built by Jomon hands and now restored to its original dimensions, that leads to the reconstructed buildings and mound excavation sites of the former settlement. Bar the odd electrical tower or fellow masked traveler in jeans and you can imagine, as you walk along it, how a Jomon adventurer might have felt upon nearing the village. When you learn that the Jomon had lined both sides of this avenue with the graves of their dead, the feeling of coming "home" to a protected place watched over by elders is even stronger.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Unearthed lacquered wooden vessel, Korekawa-Nakai site, Aomori Prefecture, final Jomon period, Important Cultural Property. Waterlogged in low wetlands, wooden and earthenware artifacts that would otherwise have been lost to the ages remain in startlingly fine shape. Photo © Korekawa Archaeological Institution

|

|

Reconstructed post-in-ground buildings, earthen mounds filled with potsherds and other artifacts, a clay pit, burial sites, and this reinstated avenue are all part of the experience at the Sannai Maruyama site, where surveys are still underway. When I was there a band of experts was studying an excavated water channel. |

The Komakino stone circle was discovered in 1989 by high-school students on a class archaeological expedition. The land on which it sits had been used in the Edo period (1603-1867) for pasturing horses and later, for farming. It was known for the conspicuous number of large rocks scattered across it, some of which had been moved off to the side over the years. When the students conducted a boring survey they found stones beneath the soil set in a circular pattern. The rest, as they say, is history. We now know that the circle's flat arena, which sits midway along a gentle incline, is in fact the earthwork of Jomon engineers, who cut the slope by removing soil from its higher end and mounding it below. Also discovered since are the remains of pit dwellings, a dumping ground, and waterworks. At 22 acres in size, the site is just right for a leisurely stroll of an hour or so -- more if you take time to sit under the oak, chestnut, and walnut trees descended from Jomon times.

|

|

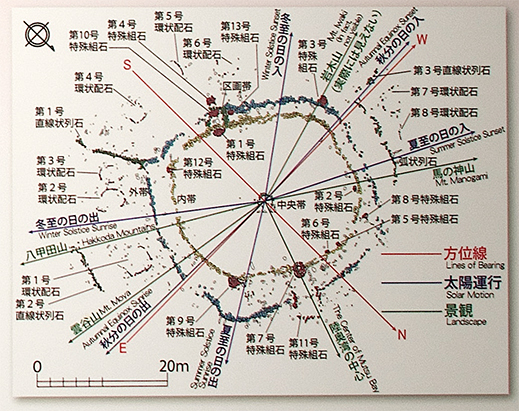

Studies of the Komakino stone circle suggest that the site may have been designed to reference the summer and winter solstices as well as key landmarks of the area: Mutsu Bay and the four mountains Moya, Hakkoda, Iwaki, and Manogami. |

An abandoned elementary school nearby was converted and reopened in 2014 as the Komakino-kan, a museum dedicated to the study of Jomon culture in general, and preservation of this site in particular. True to the spirit of the building, the exhibits are child-friendly. They explain, for example, how an excavation is conducted step-by-step, and how the Jomon people transported the stone circle's 2,900 rocks uphill from the Arakawa River 70 meters below. (The captions are also in English, and rendered with the smartest translations I've seen anywhere.) There are plenty of hands-on exhibits and even real artifacts that can be held and touched. If you would like to learn what a Jomon coprolite is, there's a matter-of-fact display on that, too -- but this one is behind glass.

Lacquered earthen vessels, Korekawa-Nakai site, Aomori Prefecture, final Jomon period, Important Cultural Properties. Photo © Korekawa Archaeological Institution |

To those who have heard of it, Jomon art primarily conjures up images of earthenware, especially pottery decorated with the rope inlay characteristic of early Jomon and for which the period is named, and the ever-endearing dogu -- anthropomorphic clay figures believed to have been used in ceremonial rites. (As iconic of Jomon culture as they are, very little is understood about them.) Lesser known is the vivid red lacquerware of the period. An entire gallery is dedicated to it at the Korekawa Archaeological Institution in Hachinohe, showcasing works of wood, basketry, and lacquer-coated earthenware. Lacquering is such a complicated process -- tapping the urushi tree, refining its sap, preparing pigment, building up the layers as they harden, polishing, and so forth. That it was mastered essentially in the middle of woods millennia ago -- having spread from traditions in China, Korea, and Vietnam, no less -- is fascinating to ponder. Ten years of growth are required before an urushi tree is ready for harvest. It's believed that the Jomon tended groves of them to maintain a steady supply of the sap, which they also used for practical purposes like weatherizing bows and other wooden tools, and strengthening their pottery.

|

|

The discovery, in the early 1990s, of the remains of earthfast pillars was the first evidence that large buildings of post-in-ground construction -- not mere pit dwellings -- had once stood on the Sannai Maruyama site. Photo © APTINET Aomori Prefecture |

One of the largest Jomon archaeological sites discovered to date, Sannai Maruyama was a year-round settlement that lasted for 1,700 years until 2200 BCE. It sits on a rich basin where the Okidate River flows into Mutsu Bay. The site is vast -- more than 100 acres -- and prolific. More than 40,000 boxes of relics have been recovered to date: Stone tools and earthenware. Hairpins fashioned of animal bone. Earrings of stone and clay. Shell armbands and pendants carved from tusks and antlers. And of course, the inimitable dogu. No less than 1,958 items excavated here have been named Important Cultural Properties. One on display at the affiliated Sanmaru Museum is a bag woven of conifer bark. Estimated to be 5,800 years old, it is the only work of such organic material found anywhere in the country that is still largely intact. That it was excavated with half a walnut shell inside telescopes the mind's eye right to the hands of its former owner.

A bank of windows inside the museum allows visitors to observe staff at work cleaning, cataloguing, and restoring artifacts. So many potsherds have emerged from the Sannai Maruyama site that an entire wall, rising six meters between two floors, has been attractively decorated with 5,000 of them. In another section of the building they are stockpiled in floor recesses and covered with plexiglass. The museum offers workshops to make different crafts, and you can restore yourself when you've seen and done it all at the restaurant with a bowl of Jomon-style noodles made of chestnut and acorn flour.

|

|

|

|

|

Jar with design of hunting scene, Late Jomon period (c. 2500-1000 BCE), prefectural treasure, Aomori Prefectural Museum

|

Though it is presently closed for renovations, the Aomori Prefectural Museum is one to keep in mind for its comprehensive overview of local archaeological sites and artifacts from the Paleolithic age to the Yayoi period (300 BCE-300 CE), when rice cultivation began. This is the place to learn how the shapes and styles of Jomon pottery changed across the millennia in between. And while Jomon designs are famously abstract, the museum has a rare vessel decorated with the narrative tale of a hunting scene. The Fuindo Collection, bequeathed by a native son of Aomori, holds some 12,000 Jomon artifacts, a smorgasbord of new favorite things to discover -- earthenware vessels and dogu figurines of all kinds, of course, but also beads made of jade, clay and stone, antler combs and lacquered bracelets, ear ornaments, woven plant-fiber textiles, even clay imprints of children's hands and feet. Whether these last objects were made in celebration or mourning is unknown, but the expression of love speaks clearly through the ages.

Photos are by the author unless otherwise noted. All photo permissions are courtesy of the respective sites and the Aomori Prefectural Government. |

|

|

Susan Rogers Chikuba

Susan Rogers Chikuba, a Tokyo-based writer, editor and translator, has been following popular culture, architecture and design in Japan for three decades. She covers the country's travel, art, literary and culinary scenes for domestic and international publications. |

|

|

|