|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

The Ins and Outs of Style: Japanese Postwar Fashion

Christopher Stephens |

|

Kansai Yamamoto's Tokyo Pop bodysuit and asymmetrical knitted leotard, both made for David Bowie in 1973, and on the right, Kite (1971), the highlight of the designer's first show in London. |

In its highest form, fashion is a thing of transcendent beauty with the simultaneous ability to charm and shock. Clothes also have the power to change the culture. Many such examples can be found in Fashion in Japan 1945-2020, which just ended at the Iwami Art Museum in Masuda, Shimane Prefecture, but will be on view again at the National Art Center, Tokyo from 9 June to 6 September. This comprehensive survey examines key sartorial trends of the last 75 years while linking them to social currents and historical events. The exhibition is made up of actual garments, photographs, drawings, magazines, and videos arranged chronologically in nine sections.

|

|

|

|

|

Monpe work pants (c. 1940s) made of meisen silk and decorated with a scrollwork pattern, flanked by Chiyo Tanaka's Pyjama Dress (1932) on the left, and a 1936 jacket and dress outfit by Mohei Itoh on the right.

|

Despite its title, the show's time frame stretches back to the 1920s, an era defined by modernism and consumerism. In the years that followed, however, this openness took a turn to the right as nationalistic views discouraged wasteful spending and foreign influences. In 1940, the Japanese government mandated the wearing of national uniforms (kokumin-fuku) as a substitute for Western fashions. The male version, a khaki suit with a militaristic appearance, was intended for daily activities and factory work. Women were expected to don monpe, loose-fitting work pants with gathered ankles that allowed for easy movement. Often made of meisen, an affordable pre-dyed silk, monpe came in a range of colors and patterns, allowing the wearer some degree of self-expression -- an option not available to men.

The term zoku (tribe) pops up time and time again in Japanese fashion history. In 1964, for instance, the young men and women who favored the Ivy League look popularized by apparel makers such as VAN began to collect near the brand's shop on Miyuki Street in Tokyo's Ginza district. Known as Miyuki-zoku (Miyuki tribe), these youths attracted the attention of law enforcement who, believing that the fashion lovers were up to something immoral if not illegal, dispersed them from the area. Later in the decade, a much less clean-cut crew, the futen-zoku (vagabond tribe), who like their hippie counterparts in the West favored long hair, jeans, and T-shirts, became a visible presence around Shinjuku Station. The '70s saw the emergence of the annon-zoku, a group of young women who took their fashion and leisure cues from the magazines an-an and non-no. In the late '70s, the takenoko-zoku (bamboo-shoot tribe) sported garish "harem suits" (loose-fitting outfits inspired by Middle Eastern garb) as they danced away the weekend in the streets of Harajuku. (They are also among the anthropological specimens featured in the video for the Talking Heads song "Once in a Lifetime.") The '80s belonged to the DC (designers' characters) brands, which were built on the vision of a single person (Issey Miyake, Yohji Yamamoto, etc.), rather than a corporate manufacturer like Renown or JUN. Female adherents of these styles, often black from head to toe, were dubbed the karasu-zoku (crow tribe) for their resemblance to the bird.

|

|

Exterior view of the Iwami Art Museum in Masuda, Shimane Prefecture.

|

Despite having opened over 15 years ago, the Iwami Art Museum is something of an overlooked gem. It is housed in a sprawling, but attractive, prefectural art center known as Grand Toit (French for "large roof") that also includes two halls for performing arts events. The complex is located in Masuda, a city of some 44,000 people at the southwestern edge of Shimane Prefecture. Along with works related to the novelist Ogai Mori (1862-1922), a native of the nearby town of Tsuwano, as well as art from the surrounding Iwami region, the museum specializes in fashion -- the reason being that Hanae Mori (b. 1926 and no relation to the writer) is from the area, too. After training as a dressmaker, Mori established her own fashion house in 1951 and made a name for herself as a movie costume designer. In 1965, she expanded her activities with her first show in New York, which led soon after to the opening of a Hanae Mori boutique in the city's Neiman Marcus department store. Mori moved to Paris in 1975, and in 1977 she became the first (and only) Asian stylist to be appointed to the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture, a trade association for high fashion numbering such legendary figures as Christian Dior and Coco Chanel among its members. In short, Mori was Japan's first high-profile international fashion designer, and in a career that spanned over half a century until her retirement in 2004, she dressed queens, princesses, and presidents' wives as well as flight attendants and Olympic athletes.

|

|

These four Hanae Mori dresses from the 1970s exemplify the designer's trademark elegance and her devotion to Japanese materials and sewing techniques.

|

Kansai Yamamoto (1944-2020) was another pioneer in the foreign fashion world. In 1971, Yamamoto became the first Japanese designer to hold a fashion show in London. There, his flamboyant styles caught the eye of David Bowie, who had recently reinvented himself with his Ziggy Stardust persona. After buying Yamamoto's Woodland Creatures, a female playsuit ornamented with a rabbit pattern, at a shop in London, Bowie was introduced to the designer and asked him to create the stage costumes for his Aladdin Sane tour. The results included Tokyo Pop (1973), a black vinyl bodysuit with huge bowed legs and red thick-soled boots, and a white kimono-like cloak emblazoned with Bowie's name, spelled out phonetically in red and black kanji. In the middle of Bowie's performances, the cape was stripped off to reveal another Yamamoto creation: a knitted leotard with a long sleeve and short leg on one side, and an exposed shoulder and full-length leg on the other. Yamamoto's work perfectly coalesced with Bowie's image as a futuristic alien, helping establish the performer as a music and fashion icon.

|

|

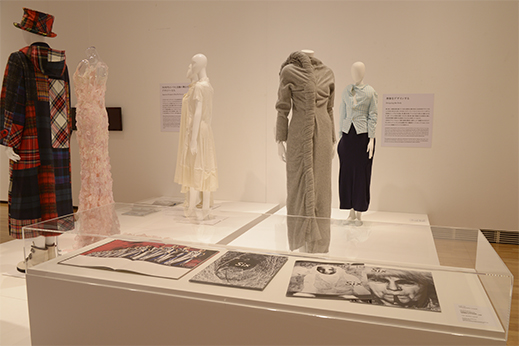

Comme des Garçons' garments (the two on the right) are distinguished by tattered edges, ill-fitting forms, and curious lumps. The glass case contains issues of the brand's short-lived magazine, Six.

|

Rei Kawakubo (b. 1942) has created some of the world's most controversial fashions with her brand Comme des Garçons. (The name, meaning "like some boys," apparently derives from a song by Françoise Hardy.) Though she launched the brand in 1969, it wasn't until Kawakubo's Paris debut in 1981 that she came to international attention. Over the next decade, her collections outraged foreign critics with her single-minded focus on black apparel accented with gaping holes, frayed edges, and exposed seams. The designer's extreme aesthetic -- easily as avant-garde as anything in contemporary art -- was a clear challenge to accepted notions of beauty, and to the traditional relationship between clothes and the body. By the '90s, Kawakubo's work had become increasingly colorful, but the designer was, if anything, even more committed to destroying fashion conventions with bumps and humps protruding from her pieces, torn and wrinkled fabrics, crooked hems and necklines, and misaligned buttons, giving her clothes the appearance of factory rejects. The filmmaker and noted fashion plate John Waters has frequently discussed his obsession with Comme des Garçons, a look that he calls "disaster at the dry cleaners." Meanwhile, Kawakubo describes her work as an "exercise in suffering."

|

|

|

|

|

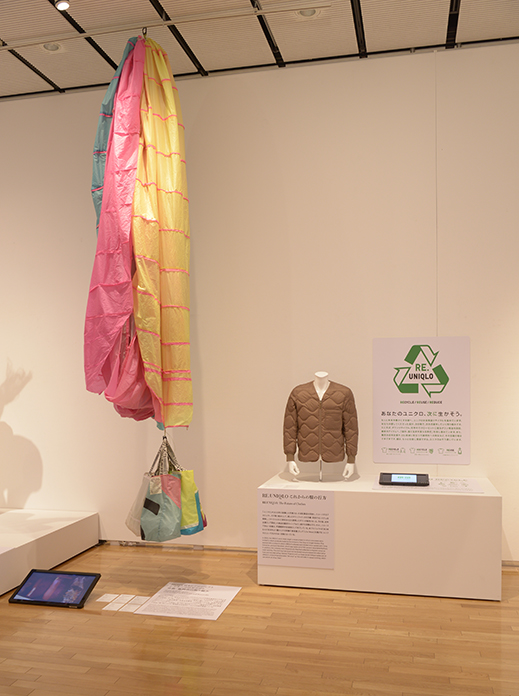

The final section of the exhibition includes recent attempts by the Theatre Products brand (the bags on the left) and Uniqlo (the jacket on the right) to reuse materials and recycle their products.

|

Summing up Fashion in Japan 1945-2020 is nearly impossible. The exhibition covers every imaginable trend and designer of the mid-to-late 20th and early 21st centuries, and also sheds light on what might lie ahead in a postscript devoted to styles of the future, touching on environmental issues, holistic approaches, and the shift away from shows and normal presentation venues. The journey is a fantastic one, which reminds us that fashion is much more than a passing fancy.

All photos by Shin'ichi Yamazaki (except museum exterior); provided by the Iwami Art Museum.

|

|

|

Christopher Stephens

Christopher Stephens has lived in the Kansai region for over 25 years. In addition to appearing in numerous catalogues for museums and art events throughout Japan, his translations on art and architecture have accompanied exhibitions in Spain, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, South Korea, and the U.S. His recent published work includes From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (MoMA Primary Documents, 2012) and Gutai: Splendid Playground (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2013). |

|

|

|